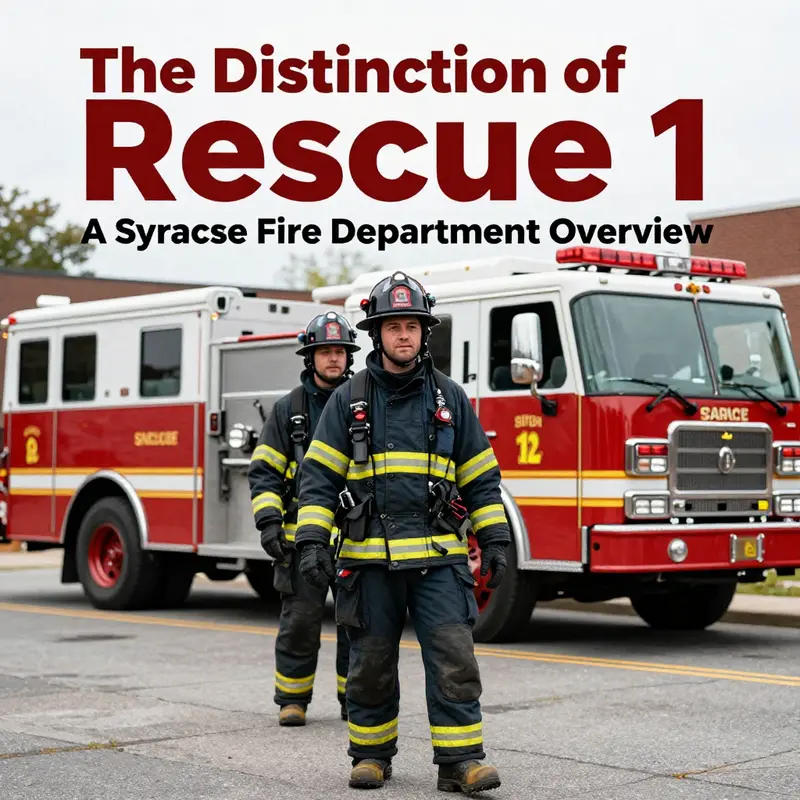

Understanding the operational dynamics of emergency services is crucial for the communities they serve. In Syracuse, New York, the local fire department maintains a specific designation system for its rescue units, yet it lacks a unit known as ‘Rescue 1’. This absence often leads to confusion among residents and professionals alike, especially when comparing to the New York City Fire Department, where Rescue 1 holds historical significance. This article will clarify the absence of Rescue 1 in the Syracuse Fire Department, delve into how their rescue units are organized, and provide a historical context that underscores the differences in operations between Syracuse and New York City. Each chapter aims to piece together a comprehensive understanding of the significance and operational framework of rescue services in Syracuse.

Distributed Rescue in Syracuse: How the Fire Department Delivers Advanced Technical Capabilities Without a Rescue 1

When people hear the term Rescue 1, they often picture a single, frontline rescue unit that stands as the department’s primary tool for extrication and complex technical rescues. In some major cities, that image aligns with reality—and it can be a recognizable emblem of readiness, a truck or unit labeled and trained specifically for that role. Yet in Syracuse, New York, the question naturally shifts from a simple label to a deeper look at how a department organizes for the unpredictable demands of urban emergencies. The Syracuse Fire Department (SFD) operates with a different philosophy and a different lineup of apparatus. There, no vehicle bears the designation Rescue 1 in the current roster, and the department’s approach to rescue work is distributed across several specialized capabilities rather than concentrated in a single unit. This distinction matters not only for how the public understands the city’s fire service, but also for how responders allocate resources, plan responses, and train for the most demanding incidents. It is a distinction grounded in history, geography, and a deliberate organizational choice that prioritizes flexibility over a single-point solution, and it offers a nuanced model for how a modern city can maintain readiness without adhering to a traditional Rescue 1 paradigm.

In Syracuse, the apparatus structure reflects a comprehensive, multi-faceted strategy for rescue operations. The department operates with engine companies and ladder companies, each equipped to perform initial, life-saving work at the scene. These frontline units carry hydraulic rescue tools and related equipment that enable rapid extrication and stabilization of victims in many crash or confinement scenarios. Rather than rely on a solitary rescue truck as the primary responder for every technical challenge, Syracuse emphasizes cross-functional capacity: the tools and skills are distributed, and the personnel are cross-trained to handle a spectrum of rescue tasks as part of the standard response framework. This model aligns with the realities of a mid-sized city where incidents can vary widely—from vehicle extrications on arterial streets to multistage emergencies in dense neighborhoods—demanding a crew capable of adapting quickly rather than awaiting a single specialized unit’s arrival.

Historically, the designation Rescue 1 has functioned as a symbol of the primary rescue capability in many fire departments across the United States. In some systems, Rescue 1 represents a fixed asset—a specific truck staffed with a dedicated crew trained for a broad range of technical rescue operations. In others, including the system adopted by Syracuse, the concept of a “first rescue” is a function rather than a fixed vehicle. Syracuse’s current roster includes Rescue 2, Rescue 3, and Rescue 4 as specialized rescue units, but there is no Rescue 1 in service today. This distinction is not an omission but rather a deliberate organizational choice rooted in the department’s emphasis on flexible, multi-purpose apparatus and a robust technical rescue capability that can be scaled up through the combined efforts of several units rather than anchored to a single vehicle. In practical terms, this means that when the sirens go out, responders do not wait for a single rescue wagon to arrive before taking action. They mobilize a coordinated package of responses that draws on the strengths of engines, ladders, and a dedicated technical rescue team, supported by mobile command resources and a heavy rescue platform capable of handling high-risk scenarios.

Understanding this approach requires looking at what the Syracuse Fire Department actually brings to the scene. A typical response begins with the first arriving engine and, if appropriate, a ladder company. These front-line units are trained and equipped to perform initial life-saving efforts, stabilize the scene, and begin vehicle stabilization or structural stabilization as needed. The tools carried by these vehicles—pneumatic spreaders, cutters, and other hydraulic rescue equipment—enable responders to pry open doors, elevate dashboards, or create space for injury assessment and patient access. The emphasis is on a rapid, first-attack capability that can immediately improve the condition of any patient while maintaining scene safety for rescue teams. In many incidents, this initial response suffices to remove a patient from a vehicle, prevent further injury, and provide critical access for medical personnel.

For more demanding or complex incidents, Syracuse relies on a dedicated Technical Rescue Team. This team is not a single unit but a cadre of trained personnel who come equipped to handle high-angle rescues, confined-space operations, or structural collapses. The team’s deployment reflects a broader concept: technical rescue is an all-hands effort that often involves multiple units working in concert. In this arrangement, the heavy rescue truck and other specialized vehicles function as force multipliers rather than as standalone “Rescue 1.” The heavy rescue truck serves a role akin to a central hub during intricate operations, offering specialized equipment, staging capability, and a command presence that helps coordinate multiple units and agencies if the incident demands it. A mobile command unit can be deployed to establish incident command, manage communications, and integrate public safety and EMS operations as the situation evolves. In this sense, the essence of Rescue 1—advanced rescue capability—exists in Syracuse not as a single vehicle, but as a distributed system that draws together the competencies of various apparatus and teams.

The decision to emphasize distributed rescue capabilities rather than a single Rescue 1 unit also reflects the practicalities of operating in a city with diverse neighborhoods, infrastructure, and incident patterns. Syracuse’s tactical landscape includes dense urban corridors, older buildings with varying construction types, and a mix of residential, commercial, and industrial zones. The recurring need is for rapid access to patients and safe, controlled access to dangerous areas. Engine and ladder companies, with their standard deployment patterns, are well suited to deliver that initial, decisive action. Where incidents exceed the scope of a single unit, the Technical Rescue Team’s expertise becomes essential, and the department’s heavy rescue truck and other specialized assets provide the necessary technical depth. In this framework, there is no single chokepoint—the city’s rescue capability lives in the readiness and interoperability of multiple units, each carrying a portion of the toolbox that collectively defines Syracuse’s approach to modern rescue work.

This arrangement also places a premium on training and interdepartmental coordination. Cross-training among engine, ladder, and technical rescue personnel ensures that responders can transition seamlessly from routine extrication to complex rescue operations as the scene demands. Training programs emphasize not only the mechanics of using hydraulic tools but also the critical thinking required to assess a scene, identify risks, and plan a staged rescue that preserves life and minimizes further harm. The Technical Rescue Team trains for high-angle operations that might involve rope systems, anchored rigging, and specialized ascent and descent techniques. They also train for confined-space rescues, where atmospheric monitoring, permit-required procedures, and a disciplined approach to permit entry are essential. Structural collapse scenarios demand a different set of skills, including listening for signs of movement, assessing shoring needs, and coordinating with engineers and building code officials to ensure that any rescue operation does not endanger both victims and responders.

One important implication of Syracuse’s approach is that the public should not expect a single, easily identifiable Rescue 1 unit parked at a station. Instead, the city presents a resilient, flexible framework that can adapt to a wide range of emergencies. When a call comes in, the first responders on the minimum initial inspection of the scene decide how to proceed. If the incident is straightforward, they may stabilize and extricate with the resources already on board. If it becomes more technically demanding, the Technical Rescue Team is brought in, often with the heavy rescue truck, to augment the operation. The process relies on clear communication, rapid decision-making, and a logistics chain that ensures that the right tools and the right people are available without delay. While the nomenclature might differ from cities that maintain a Rescue 1 as a standalone unit, the readiness and capability—when needed—are in place, and perhaps even more adaptable because they are not bound to a single vehicle’s limitations.

The department’s philosophy also aligns with the practical realities of mutual aid and regional coordination. Syracuse sits within a network of nearby departments and regional response plans that can supplement its capabilities during large-scale emergencies. Mutual aid allows for the swift arrival of additional personnel and specialized equipment when incidents exceed the city’s internal capacity. In such cases, the presence of a mobile command unit becomes especially valuable, providing a centralized node from which agencies can coordinate complex rescue operations, manage safety zones, and optimize the use of limited resources. The distributed rescue model thus leverages both internal depth and external partnerships to deliver a robust, scalable response that can adapt to incidents of varying complexity and scope.

From a public information perspective, clarity about the city’s approach helps reduce confusion around labels like Rescue 1 and sets accurate expectations for what responders can deliver. It is easy to assume that a single unit must exist to perform a specific function, but in practice, Syracuse demonstrates that a well-trained workforce, a fleet of complementary vehicles, and a dedicated technical rescue team can produce equivalent or even superior outcomes by bringing together diverse capabilities at the right moment. The absence of a Rescue 1 designation does not imply a lack of readiness; rather, it signals a mature, integrated system where different pieces of equipment, trained personnel, and response plans combine to deliver comprehensive rescue services.

To readers seeking a more concrete sense of how this system operates on a typical call, consider how a scene might unfold. A vehicle crash on a busy street triggers the first-arriving engine to pull in, assess hazards, and deploy stabilization measures. If a patient is trapped, responders begin carefully creating access paths while safeguarding the vehicle’s occupants and the surrounding environment. The engine crew may initiate patient care en route to the hospital, ensuring that life-saving measures begin as soon as possible. If the complexity of the entrapment exceeds the capabilities of the front-line units, the Technical Rescue Team is alerted. They arrive with the heavy rescue truck and a tailored set of tools designed for more intricate extrication, including advanced stabilization gear, rigging components, and equipment that supports complex access. The mobile command unit may be deployed to coordinate communications, manage air monitoring and scene safety, and liaise with the medical crew and dispatch. In this way, the rescue operation progresses through an orchestrated sequence in which no single vehicle bears the entire burden, but every deployed asset contributes a precise function to the collective mission: to reach the patient quickly, extract them safely, and transfer them to medical care with minimum delay.

This distributed model also emphasizes the importance of prevention, safety, and ongoing professional development. The Syracuse Fire Department prioritizes training that strengthens not only technical rescue skills but also the decision-making frameworks that govern when to escalate. For example, responders learn to assess the structural integrity of a building before attempting access, to interpret smoke and heat indicators that might signal hidden dangers, and to work within a team that communicates clearly across multiple units. Such training reinforces the idea that rescue work is not merely about possessing the right tool, but about knowing when and how to deploy it within a broader tactical plan. It also highlights the value of a culture that encourages collaboration, continuous improvement, and readiness to adapt to evolving incident patterns. This culture sustains a system where the grouped capabilities—engines, ladders, the Technical Rescue Team, the mobile command unit, and the heavy rescue truck—create a synergistic effect: a response that is greater than the sum of its parts.

For readers who want to explore this subject through a practical, real-world lens, it is helpful to connect the discussion to broader discussions about fire safety training and certification. A resource focusing on essential safety training can illuminate how responders prepare for the kinds of scenarios described here. Fire Safety Essentials Certification Training offers a lens into the ongoing education that underpins the department’s readiness. This emphasis on training does not merely fill time; it builds muscle memory, enhances confidence, and ensures that responders can execute complex rescue operations with discipline and efficiency when every second counts. The Syracuse model underscores that preparation begins long before a call arrives and continues as responders practice and refine their roles in a deliberately layered system.

The public-facing takeaway from Syracuse’s approach is not a slogan about a single, iconic Rescue 1 but a recognition of a resilient architecture of rescue capabilities. It is a system designed to deliver the right mix of tools and expertise at the right moment, with the flexibility to scale in response to incident dynamics. In practice, this means that residents benefit from prompt initial action by the first-arriving engines and ladders, followed by the targeted expertise of the Technical Rescue Team when needed, all under the overall coordination of a mobile command unit if the incident demands it. When communities understand how this architecture works, they gain a clearer sense of what to expect during emergencies and why certain units arrive together in a coordinated fashion rather than in a predesignated, single-vehicle sequence. This understanding also fosters confidence in the department’s capability to adapt to evolving risks, from vehicle entrapments on major corridors to more specialized scenarios that require advanced rescue techniques.

To preserve the integrity of this chapter’s flow and to keep focus on Syracuse’s unique approach, it is important to reiterate the core premise: Rescue 1, as a fixed unit, does not exist in the Syracuse Fire Department’s current apparatus roster. Instead, the department has built a distributed rescue capability anchored by a mix of frontline response assets and a dedicated technical rescue team, supported by specialized vehicles and a mobile command presence. This configuration aligns with the city’s needs and resources, enabling effective rescue operations across a broad spectrum of emergencies. It also speaks to a broader truth about modern fire services: success in rescue work often depends on the choreography of many parts rather than the performance of a single performer. In Syracuse, the choreography is deliberate, practiced, and capable of adapting to the scene as it unfolds.

As readers continue to explore the topic, they may find additional, official details about the Syracuse Fire Department’s apparatus and organizational structure on the city’s fire department website. This resource provides the latest information on how the department assigns apparatus, how its technical rescue capabilities are organized, and how responders collaborate across units during complex incidents. Accessing authoritative sources is essential for accuracy, especially when readers are seeking precise designations or station-by-station breakdowns. In Syracuse, the absence of Rescue 1 is not a gap in capability; it is a reflection of a well-considered, comprehensive approach to rescue that leverages the strengths of multiple units and specialized teams working together to save lives.

In closing, the Syracuse Fire Department’s approach to rescue work embodies a modern, adaptable philosophy. It rejects the notion that a single vehicle must shoulder the entire burden of technical rescue. Instead, it distributes capability across a spectrum of resources designed to complement one another. The first-in units begin the life-saving work; the technical rescue team provides advanced capabilities for the most challenging scenarios; and the mobile command unit ties the operation together, guiding safety, coordination, and resource deployment. The result is a resilient, scalable rescue framework that can respond effectively to a city’s diverse needs while maintaining a clear, cohesive strategic posture. The question “which station is Rescue 1?” is thus reframed into a more informative inquiry: Which combination of units and teams can deliver the necessary rescue capabilities when urgency is highest, and how does Syracuse ensure that combination remains ready, trained, and synchronized for every call? The answer lies not in a single designation, but in a coordinated system built to protect life by moving together, efficiently and decisively, at the speed of emergencies.

Naming the Rescue: How Syracuse Fire Department Numbers Its Units and Why Rescue 1 Isn’t in Syracuse

The question of where Rescue 1 sits in Syracuse is common, but the answer is: there is no Rescue 1 in the Syracuse Fire Department’s current roster. This reflects a broader pattern: many departments organize rescue capability as a family of units numbered by function, capability, and readiness rather than a single fixed unit.

Rescue 2, 3, and 4 may be primary rescue units with distinct roles, while higher numbers (such as Rescue 10, 11, 12) designate heavy, technical, or hazardous materials responses. The numbers act as shorthand for dispatchers, incident commanders, and field crews, informing them which tools and crew will respond.

FDNY Rescue 1 is historically significant and belongs to a different organizational lineage; Syracuse’s approach aims for modularity and interoperability at a local scale.

For the public, the takeaway is that a rescue designation is a signal about capability, not a pledge that a single vehicle is the entire solution. To verify, consult the official Syracuse Fire Department roster on their site.

Rescue 1 Across Rivers and Records: Why Syracuse Has No Rescue 1 and What That Difference Reveals About Fire-Rescue History

Inquiries about Rescue 1 often travel across river and time, prompting a quick, practical answer: Syracuse does not station a unit called Rescue 1. The Syracuse Fire Department operates its own fleet with a distinct numbering tradition, including Rescue 2, Rescue 3, and Rescue 4. Yet the name Rescue 1 carries a centuries-old weight elsewhere, most prominently in New York City, where Rescue 1 is not just a designation but a symbol of urban rescue evolution. The question thus becomes less about a single door at a specific firehouse and more about how two neighboring, yet organizationally different, fire services conceived and built their rescue capabilities. Reading the question this way invites a broader reflection on how urban scale, training culture, and regional cooperation shape the naming and deployment of rescue units. It invites a historian’s lens as well as a firefighter’s sense of practical readiness. And it naturally leads to a comparison that clarifies why a unit bearing the label Rescue 1 exists in one city and not in the other.

To understand the Syracuse answer, we begin with the broader, historical arc of Rescue 1 in New York City. Rescue 1 was established in 1915 as the city’s first dedicated rescue unit within the Fire Department of New York (FDNY). The creation of Rescue 1 reflected a growing recognition that the urban landscape demanded a specialized capability beyond traditional firefighting. The city’s engineers of rescue operations looked ahead to structural complexities, concentrated populations, and the kinds of emergencies that tested not only hoses and ladders but also the dexterity of technicians who could extricate people from wreckage, stabilize crumbling structures, and deploy equipment designed to lift, pry, cut, or restrain dangerous situations. In that early era, Rescue 1 wore many hats: it handled complex structural rescues, large-scale collapses, and emergencies that demanded a blend of physical strength, technical skill, and evolving technology. Its members trained rigorously, adopting equipment that was cutting edge for its time and that would evolve into the heavy rescue toolkit still recognized today. The unit’s early equipment included self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), heavy rescue gear, and hydraulic spreaders—a constellation of tools that allowed responders to reach victims in tight spaces, under debris, or behind damaged walls.

As decades passed, Rescue 1’s role expanded in tandem with urban growth, the development of high-rise construction, and the increasing sophistication of the city’s emergency response network. The unit became a touchstone for what a modern urban rescue operation could be. In practice, Rescue 1’s missions would often require swift, coordinated action with other special units, including engineers, collapse teams, and, when needed, aviation or chemical response teams. The unit’s training and standard procedures evolved with the city’s evolving risk profile. Then came a defining moment in American emergency history: the attacks of September 11, 2001. Rescue 1, along with hundreds of FDNY units, was thrust into the most perilous urban rescue mission in recent memory. Members entered the North Tower to assist survivors and perform critical stabilization and rescue tasks under conditions that tested the limits of training, equipment, and spirit. The losses suffered that day—on a scale that touched every firehouse and every rescue company—cemented Rescue 1’s legacy in public memory. The courage, commitment, and sacrifices of Rescue 1’s members became a national emblem of urban resilience and the bravery of those who face the worst while seeking to save others.

In the years that followed, the FDNY recognized the need to memorialize and preserve the unit’s history. A portion of West 43rd Street was renamed to honor Captain Terry Hatton and others who died in the line of duty, a public commemoration that underscores how deeply the unit’s story is tied to the city’s memory. Today, the unit’s vehicles carry the tribute “T.H.”—a constant reminder of the individuals who gave their lives serving on Rescue 1. The story of Rescue 1, then, is not only about equipment and tactics. It is about a culture of rescue work in a dense urban environment, a culture that learned through experience, tragedy, and continual refinement how to keep pace with ever-more challenging emergencies.

This historical arc helps illuminate why Syracuse’s fire department developed its own rescue structure without adopting a Rescue 1 designation. Syracuse’s approach reflects a different set of priorities shaped by geography, governance, and regional cooperation. The Syracuse Fire Department operates in a city sized and organized to emphasize municipal efficiency and community protection within a regional framework. It maintains a trio of specialized rescue units—Rescue 2, Rescue 3, and Rescue 4—designed to respond across neighborhoods, industrial corridors, and major emergency sites. The absence of a Rescue 1 in Syracuse is not a deficiency but a reflection of how a city adapts its apparatus and command structure to local needs. Where FDNY’s Rescue 1 emerged from a central, city-wide specialty program designed to tackle a very specific urban-scale problem set, Syracuse built a broader heavy-rescue network that leverages mutual aid, cross-training, and a rotating fleet to cover similar hazards without replicating the same unit identity.

The practical implication for residents and readers of this chapter is not a dispute over nomenclature but a clearer understanding of how rescue work is organized on the ground. Syracuse’s Rescue 2, Rescue 3, and Rescue 4 function as a complement to the city’s firefighting capacity, with crews trained to handle technical rescues, collapsed structures, vehicle extrications, hazardous materials responses, and swift water or confined-space emergencies when they arise. The exact assignment of a given rescue unit to a station is a matter of operational planning, stand-by readiness, and mutual-aid agreements rather than a fixed, city-wide tradition of one unit being the “first” rescue. In a large city like FDNY, a Rescue 1 can serve as a flagship for training, public outreach, and a rapid response to highly specialized incidents. In a mid-size city like Syracuse, the emphasis falls on maintaining a nimble, regionally integrated network that can mobilize multiple rescue assets in concert when a major event occurs. The result is a different but equally rigorous standard for readiness and capability, one that aligns with the city’s needs and its governance structure.

To ground this discussion in verifiable fact, the Syracuse Fire Department’s official materials, including their public-facing communications and city resources, consistently show a classification of Rescue 2, Rescue 3, and Rescue 4 as their specialized rescue units. They do not list a Rescue 1 as part of the current roster. In practical terms, this means a reader asking, “Which station houses Rescue 1 in Syracuse?” will be directed to the clear answer: there is no Rescue 1 in Syracuse, and any confusion often stems from comparing two different fire-service cultures rather than from a single, static roster. The official Syracuse City Fire Department site remains the authoritative place to verify current apparatus assignments and to understand how the department organizes its rescue capabilities. The variation between FDNY and SFD underscores the broader point that the design and naming of rescue units are closely tied to organizational philosophy, regional risk, and the historical development of each city’s emergency services.

Yet, within that difference lies a shared thread that runs through all serious rescue work. Both cities, in their own ways, rely on a deep bench of training, an array of specialized tools, and a philosophy that emphasizes rapid, coordinated action when lives are at stake. The memory of past tragedies, including the losses suffered on 9/11 for FDNY, continually informs modern practice. It pushes departments to invest in heavy rescue capabilities, to maintain high levels of readiness, and to keep the lines of communication open with surrounding jurisdictions so that assistance can flow quickly when incidents exceed the capacity of a single unit or a single city. The history of Rescue 1 thus becomes a lens through which we can view contemporary practice: not a static label but a dynamic story of how urban rescue tactics evolve in response to changing hazards, city growth, and the enduring need to save lives under pressure.

The difference in naming and deployment also speaks to how communities relate to memory and authority. FDNY’s Rescue 1 is not only a functional unit; it is a storied institution, one embedded in the city’s identity and commemorated in public space. In Syracuse, the absence of a Rescue 1 reflects a different relationship with the past and a different axis of coordination—one that centers on regional resilience and everyday reliability rather than a single high-profile emblem. This distinction matters for researchers, residents, and emergency-management planners. It illustrates how two nearby cities can pursue parallel missions—protecting people from fires, collapses, vehicle crashes, and hazardous intrusions—yet do so through distinct organizational choices. Those choices shape how residents understand their city’s readiness, how responders perceive their own careers, and how outsiders interpret the public face of emergency services.

For readers who want to dig deeper into the FDNY chapter of Rescue 1’s history, the official FDNY history page offers a detailed account, including the unit’s long arc from 1915 through the modern era. The material there emphasizes Rescue 1’s foundational role in urban rescue, its evolution, and the memory of those who served. It helps place Syracuse’s contemporary rescue network in a broader historical frame, clarifying why one city developed a high-profile, long-standing rescue identity while the other shaped a network designed for regional coordination and practical coverage across neighborhoods.

The practical takeaway for readers who operate in or study municipal fire services is that unit names themselves are less important than the capabilities they represent and the systems that sustain them. Rescue work hinges on training, readiness, and the ability to adapt quickly to a changing incident landscape. Two cities might converge in capabilities yet diverge in branding, structure, and succession planning. When someone asks about a Rescue 1 in Syracuse, the best answer is not a number on a map but a description of how Syracuse equips its teams and coordinates with neighboring departments. It is about understanding how a city organizes its heavy-rescue assets—through Rescue 2, Rescue 3, and Rescue 4 in Syracuse—while FDNY maintains a Rescue 1 with a different historical and institutional footprint. In the end, the common objective remains the same: to move quickly, work safely, and bring people home.

As you reflect on these differences, consider the broader implications for how communities teach resilience to younger firefighters and how they communicate about public safety to residents. Clear language about the purpose of each unit helps avoid confusion and aligns expectations with reality. It also highlights the importance of ongoing training, equipment maintenance, and cross-jurisdictional cooperation, all of which keep rescue operations effective regardless of unit name. The question about Rescue 1 in Syracuse thus becomes a gateway to a richer conversation about how municipalities steward their emergency services in the 21st century—balancing tradition and memory with practical, on-the-ground readiness.

For readers seeking further context beyond this narrative, an examination of NYC Rescue 1’s long arc provides a complementary perspective on how a single unit can shape urban rescue practice across time. The FDNY Rescue 1 history reflects not only technical evolution but also the human stories behind the badge, the tools, and the training. It is a reminder that the labels we use in the firehouse are means to an end: saving lives under pressure, learning from every call, and honoring those who gave their all in service to the city. The Syracuse experience, with its own roster and regional approach, demonstrates that resilience is not a monolith; it is a tapestry woven from local needs, shared training, and steadfast commitment to community protection.

Readers may also find value in engaging with professional resources that track rescue operations and training standards. For those who want to explore a broader conversation about training and readiness in the field, a visit to the FIRE RESCUE blog offers context on the essential knowledge and qualifications that underpin these demanding roles. The blog acts as a touchpoint for understanding how firefighters prepare themselves to meet diverse hazards and how departments cultivate a culture of ongoing learning and practice. This broader lens helps connect the Syracuse question to a national conversation about how rescue units evolve, share best practices, and stay ready to respond when every second counts. To explore this resource, you can visit the FIRE RESCUE blog.

In summary, the question of which station houses Rescue 1 in Syracuse points toward a larger, instructive distinction between two urban profiles. FDNY’s Rescue 1 stands as a historic and symbolic pinnacle of urban rescue, a unit that built and shaped a field over more than a century and that continues to inform modern practice—and, in memory, to honor those lost on a day that redefined the meaning of service. Syracuse, by contrast, embodies a practical, regional approach to rescue that emphasizes breadth of coverage, flexible mobilization, and collaborative operations across jurisdictions. Both models reflect the same core aim: to protect life when danger is most acute. For residents of Syracuse and readers elsewhere, the key is recognizing how each system achieves that aim through different organizational choices, while maintaining the shared dedication that defines the profession.

For authoritative details on Rescue 1’s history and legacy, you can explore the FDNY’s official history page dedicated to Rescue 1 at https://www.nyc.gov/site/fdny/about/history/rescue1.page. This external resource provides a comprehensive account of the unit’s origins, evolution, and enduring significance within New York City’s public safety narrative.

If you’re seeking additional perspectives on how departments structure their rescue capabilities in practice, consider engaging with broader industry discussions and training resources available through internal and external references. A useful starting point is the FIRE RESCUE blog, which offers insights into the standards, certification processes, and career pathways that support the work of rescue teams across cities and regions. For context on training and readiness, see the detailed coverage at firenrescue.net/blog.

Final thoughts

In summary, the absence of a unit designated as Rescue 1 within the Syracuse Fire Department highlights the distinct differences in emergency services between Syracuse and New York City. While Syracuse operates under its own unique system, the legacy of Rescue 1 continues to be a topic of interest and respect within the firefighting community. Understanding these differences not only clarifies public perception but also honors the contributions of rescue units wherever they serve. Community members are encouraged to familiarize themselves with their local fire department for enhanced safety awareness and preparedness.