Fire brigades have evolved significantly beyond their traditional role of extinguishing flames. Today, they serve as critical entities in various rescue operations, tackling emergencies that range from vehicle extrications to natural disasters. This transformation reflects the pressing need for comprehensive emergency services in our communities. Understanding the multifaceted responsibilities of fire brigades reveals their vital contributions to public safety. The subsequent chapters delve into their specific rescue roles, the types of operations they undertake, the equipment and training that empower them, and the challenges they face in ensuring effective rescue outcomes.

Beyond Flames: How Fire Brigades Lead Modern Rescue Operations

The expanding remit of fire brigades has reshaped how communities respond to emergencies. Once defined narrowly by extinguishing fires, contemporary brigades now manage a broad range of rescue tasks. They arrive at road crashes, flood scenes, chemical leaks, and collapsed structures. Their role is to preserve life, stabilize hazards, and protect property. This chapter traces that evolution, and explains how training, equipment, and community integration make fire brigades indispensable rescue agencies.

Fire brigades today operate as multi-hazard rescue services. Declines in structural fires have shifted daily call profiles. Crews increasingly respond to vehicle extrications after collisions. They manage swift-water rescues in flood-prone areas. They stabilize buildings after partial collapses. They handle hazardous materials incidents, and deliver urgent medical care when ambulances are delayed. Each task demands different skills, tools, and incident tactics. Yet a common thread binds them: firefighters are trained to make risky environments survivable for victims and fellow responders.

This expansion is particularly visible among volunteer fire brigades. Volunteers often serve in rural and suburban communities with limited emergency services. In many countries, volunteer brigades respond to local flooding, fallen or collapsed trees, damaged buildings, and other hazards. They form integral parts of national internal security systems and work under the guidance of centralized authorities. That formal recognition brings standardized procedures, accountability, and access to training resources.

Training is the backbone of effective rescue work. Firefighters must be competent in technical rescue skills, basic and advanced medical care, and hazardous materials mitigation. Training programs emphasize task-specific drills, teamwork, and real-world scenario practice. Repetition builds muscle memory. It also reduces cognitive overload in high-pressure moments. Good training fosters situational awareness and mutual trust among crew members. These qualities shorten response times and improve outcomes for trapped or injured people.

Beyond technical skill, training addresses the psychological demands of rescue work. Firefighters often confront traumatic scenes. Structured training prepares them to manage stress on scene and afterward. Peer support and debriefing are routine in many brigades. These measures preserve decision-making capacity during operations. They also help retain personnel by reducing burnout and secondary trauma.

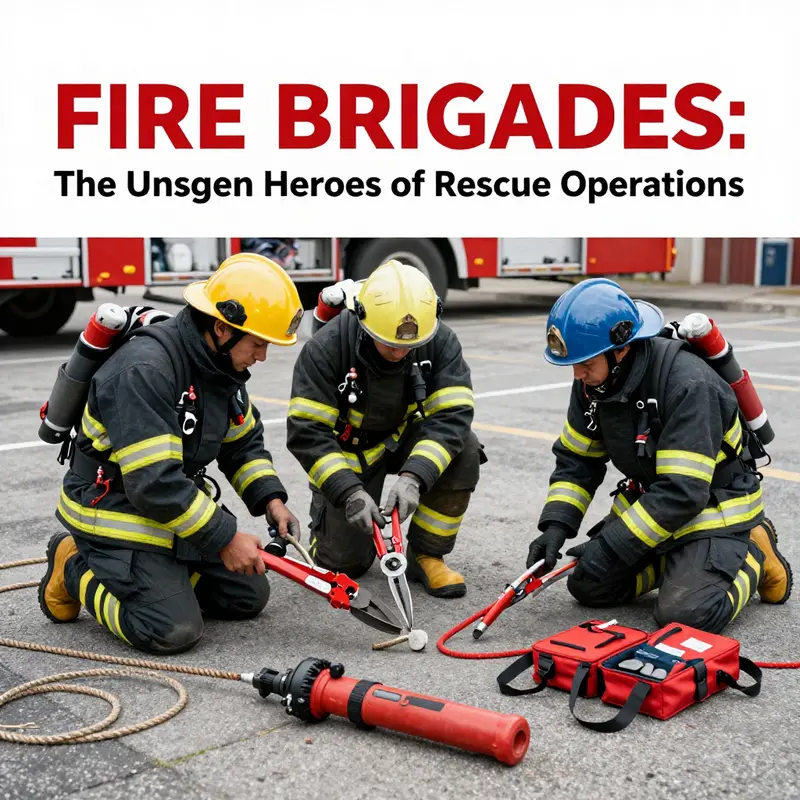

Specialized equipment complements training and expands what brigades can do. Hydraulic rescue tools, commonly called the “jaws of life,” free people trapped in vehicle wreckage. Lifting bags and cribbing stabilize collapsed or tilting structures. Thermal imaging cameras locate victims through smoke or debris. Rope systems enable access to cliffs, ravines, and tall buildings. Boats and swift-water gear save people in moving water. Personal protective equipment shields responders from fire, chemicals, and biological hazards. Each tool broadens operational capability. But training is required to use these tools safely and effectively.

Integration with other agencies is essential. Fire brigades rarely operate alone in complex incidents. They coordinate with ambulance services, police, utility companies, environmental agencies, and disaster response teams. Clear incident command systems prevent duplication and confusion. Shared communication protocols allow unified situational pictures. Joint exercises create familiarity among different responders. That familiarity becomes critical during large-scale events, when dozens of teams must work together under intense pressure.

Volunteer brigades face particular challenges and opportunities in this environment. Limited budgets can restrict equipment acquisition and advanced training. Yet volunteers often bring deep local knowledge. They know road layouts, seasonal hazards, and vulnerable populations. Many brigades build partnerships with regional agencies and training centers to bridge capability gaps. These alliances ensure volunteers are not isolated, and that rural communities receive competent rescue coverage.

Operational readiness also depends on maintenance and logistics. Rescue equipment must be inspected and serviced. Vehicles require upkeep. Supply chains for specialized parts must be reliable. Brigades maintain cache systems for incident-specific gear. They prepare staging plans for large events. Efficient logistics reduce time to patient care and can save lives.

Another critical element is community risk reduction. Fire brigades increasingly engage in prevention work. They advise on flood defenses, building safety, and chemical storage. They run public training on evacuation and first aid. Prevention lowers overall incident rates and reduces the need for high-risk rescue operations. It also strengthens public trust and participation, which supports volunteer recruitment and funding.

Modern rescue operations also rely on standards and certification. Internationally recognized training standards define competencies for technical rescue, hazardous materials, and medical interventions. These standards create a common language and set expectations for performance. They also guide procurement of equipment and the design of training facilities. For example, dedicated training towers and simulation centers allow crews to rehearse complex scenarios in controlled settings. Investing in such infrastructure yields better prepared personnel and safer operations.

Technology continues to influence rescue approaches. Drones provide rapid aerial reconnaissance at collapse sites and fires. They map hazards and locate victims in areas that are dangerous for crews to enter. Data from drones and sensors can be integrated into command software. That integration improves decision-making and resource allocation. However, technology does not replace the fundamental need for trained responders on the ground. It amplifies their reach and situational awareness.

Ultimately, the value of fire brigades in rescue work lies in the convergence of training, equipment, coordination, and community trust. When a brigade arrives at an emergency, its members bring practiced skills, trusted tools, and an ability to coordinate effectively with partners. That combination reduces fatalities and long-term harm. It also reinforces the brigade’s role as a first responder for all hazards, not just fires.

Sustaining this capability requires investment and policy support. Funding must cover training, equipment lifecycle costs, and staff welfare. Policymakers should recognize the multi-role nature of brigades and provide resources accordingly. Community leaders can support volunteer recruitment and local prevention programs. Meanwhile, continuous learning—from after-action reviews to updated technical standards—keeps practices current.

For those seeking deeper technical guidance and standards, refer to internationally recognized training frameworks. The National Fire Protection Association maintains accessible documentation on training and competencies for modern fire service roles. More information can be found at: https://www.nfpa.org/About-the-NFPA/News-and-Resources/Press-Releases/2025/January/2025-01-08-International-Fire-Service-Training-Standards

For an example of how training infrastructure supports readiness, see the account of the firefighter training tower dedication. It shows how practical facilities translate investment into safer, more capable crews.

In sum, fire brigades now lead broad rescue efforts. They combine technical rescue skills, medical care, hazardous materials mitigation, and community prevention work. Their effectiveness depends on training, equipment, coordination, and resilience. As emergencies evolve, brigades will continue to adapt, remaining central to saving lives and protecting communities.

Beyond the Flame: The Expanding Rescue Mission of Fire Brigades

Fire brigades have long been the front line against flames, but their real strength emerges in the broad spectrum of rescue operations that unfold in the wake of danger. The traditional image of firefighters battling a blaze still holds cultural resonance, yet the daily reality for many brigades—especially the volunteer units that form the heart of many communities—has shifted toward multi-hazard response. In this chapter, we trace how rescue work has become an intrinsic part of what a fire service does, how responders prepare for the diverse demands of modern emergencies, and why this evolution matters for public safety. The arc is not about replacing firefighting with rescue; it is about expanding capability so that a team that arrives first on a scene can stabilize, secure, and save lives across a wide range of scenarios. The story is one of training, collaboration, and continuous adaptation, where equipment, tactics, and governance align to meet evolving risks without sacrificing the core mission: to preserve life when seconds count. Within this expanded mission, fire brigades operate as a unified emergency response system that links technical skill with medical judgment and environmental stewardship, all under the common banner of protecting communities when danger arises in any form.

To understand the current rescue remit of fire brigades, it helps to consider the kinds of emergencies that routinely demand their presence beyond extinguishing fires. Technical rescue, medical rescue, water rescue, high-angle rescue, and environmental or hazardous materials (HAZMAT) rescue represent a ladder of response, each rung requiring specific training, equipment, and operating procedures. It is easy to overlook how seamlessly these tasks interweave on a single incident. When a road traffic collision occurs, for instance, responders must perform patient care, stabilize vehicle occupants, and extract people without aggravating injuries. In a flood, the same crew might need swiftwater rescue capabilities, public safety management, and coordination with other agencies to prevent downstream hazards. In a collapsed building, responders transition from search to shoring to extrication while managing structural stability and crew safety. The common thread is a mindset that prioritizes speed, safety, and precision, with a toolkit that is layered and adaptable rather than siloed by discipline. As the knowledge base notes, volunteer brigades and professional services today carry out a continuum of rescue tasks alongside traditional firefighting, which creates a flexible backbone for community resilience.

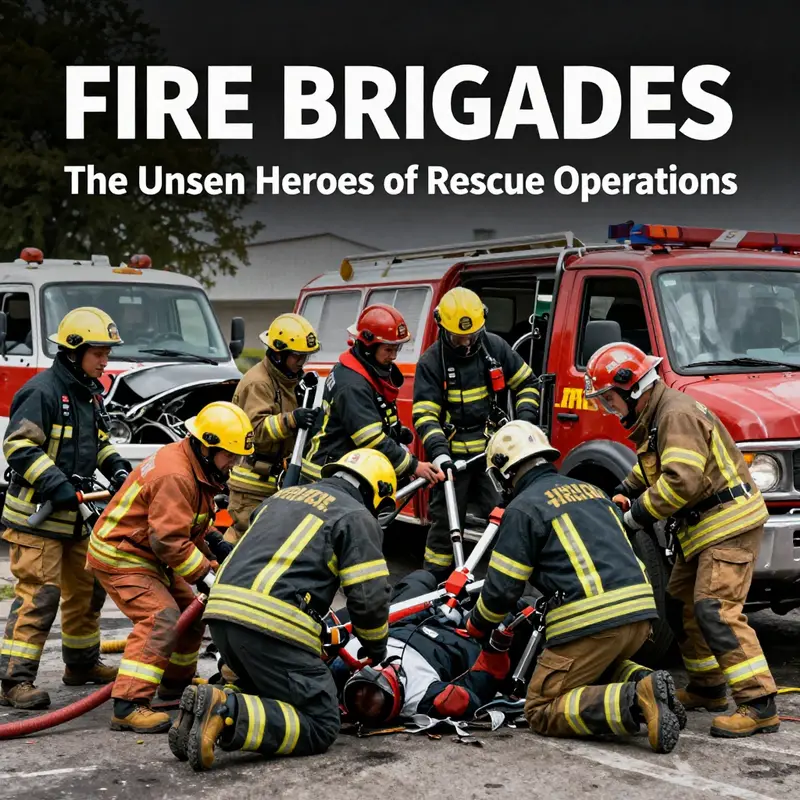

Technical rescue forms the backbone of this expanded scope. It encompasses extrication from vehicles after crashes, stabilization of partially collapsed structures, and operations in confined spaces where access is limited and risk is high. Technical rescue requires more than raw bravado; it demands meticulous planning, scene assessment, and a deep repertoire of rigging and rescue techniques. Volunteers and professionals alike must be proficient in evaluating hazards, coordinating with bystanders and municipal services, and using equipment that enables controlled release of energy and careful patient handling. The requirement is not merely to remove a person from danger but to do so in a way that preserves bodily integrity and minimizes additional trauma. Training programs emphasize scenario-based practice so that responders can transfer skills quickly to real emergencies, and they stress ongoing certification to keep pace with evolving standards. The shift toward broader rescue duties has driven brigades to invest in advanced tools, rescue rigs, cutting devices, and stabilization systems that enable them to tackle a range of trapped-person situations. The focus remains practical and outcome-driven: a successful extrication means a person reaches an ambulance with the minimum possible delay and the least risk of secondary injury.

Medical rescue adds another layer of complexity, blending fire service capability with emergency medical principles. Firefighters often arrive at the same time as or before paramedics and assume a critical role in scene assessment, rapid triage, and initial medical management. The approach hinges on quick, decisive action to control life-threatening conditions, manage bleeding, secure airways, and maintain circulation while the patient is being transported to definitive care. This is not an either/or choice between firefighting and medical care; it is a continuum where early intervention can dramatically influence outcomes. Training emphasizes not only medical techniques but also patient handling in austere environments, communication with EMS partners, and the ethical dimensions of on-scene decision-making. The result is a more resilient response system: a crew that can assess the medical urgency, provide essential care, and support longer-term clinical treatment once the patient reaches hospital services. In many communities, this integrated model reduces scene times and improves survival rates, especially when time-sensitive interventions are required before professional medical teams can complete handover.

Water rescue, whether in floods, rivers, or other waterways, tests a brigade’s versatility and courage. Water environments add layers of risk, including current strength, hypothermia, entrapment, and the challenge of operating from boats, shorelines, or improvised platforms. Water rescue teams train to assess flow dynamics, plan rescues with preplanned routes, and deploy search patterns that minimize the chance of additional victims or unplanned drownings. The capabilities extend beyond rescuing individuals; they include safeguarding bystanders, securing access for medical teams, and coordinating with civil authorities to prevent further harm from floods or rising waters. The toolkit for water rescue blends flotation devices, boats, throw bags, throw lines, and communication systems that remain reliable regardless of weather conditions. In many regions, recurring flood events have taught responders to anticipate swiftwater sequences, develop river rescue rehearsals, and build a culture of vigilance that keeps communities safer during seasonal threats. The experience of water rescue is a constant reminder that emergencies do not respect boundaries between land, air, or water; they demand a unified, multi-modal response.

High-angle rescue broadens the spectrum further into vertical spaces, from cliff faces to towers, rooftops, or precarious ledges where gravity and exposure are constant hazards. The essence of high-angle rescue is not just the technical rope work but the discipline of risk assessment, communication, and teamwork at height. Rope systems require careful rigging, redundant safety measures, and precise coordination among team members—the belayer, the rescuer, the medical officer, and the incident commander all play critical roles. The preparation for these missions involves long-term training cycles that integrate physical fitness, technical proficiency, and mental readiness. The outcomes hinge on a balanced approach: respect for the dangers of height and the confidence to apply complex procedures in dynamic settings. High-angle rescue also highlights the way modern brigades blend traditional firefighting with specialized operations, ensuring that crews can reach victims behind obstacles, across irregular terrain, or at great altitudes while maintaining personal safety and team cohesion.

Environmental and hazardous materials rescue adds an urgent, sometimes unseen dimension to rescue work. Incidents involving chemical spills, toxic releases, or environmental contamination require responders to protect themselves while containing the hazard and preventing public exposure. HAZMAT rescue carries its own playbook: detection, containment, decontamination, and careful patient handling when injuries have occurred or exposure has compromised well-being. The safety culture around these operations is anchored in robust standard operating procedures, detailed hazard assessments, and close cooperation with public health and environmental authorities. The growth of this area reflects a society that grapples with chemical and environmental risks in everyday life, from industrial accidents to accidental releases during storms or floods. Fire brigades must stay current on the latest protective equipment, monitoring devices, and decontamination practices, all while maintaining readiness to perform patient care or rescue under potentially compromised conditions. The complexity of these missions underscores why ongoing training is essential and why national standards increasingly emphasize cross-disciplinary competencies that bridge firefighting, medicine, and environmental science.

Across these Rescue domains, one trend remains clear: the burden of rescue work is shifting toward multi-disciplinary readiness. Recent studies document a rising frequency of non-fire emergencies, including road accidents, natural disasters, and environmental incidents. This shift has meaningful implications for how brigades recruit, train, and organize themselves. Volunteer fire brigades, in particular, often serve diverse communities with limited resources, so their ability to marshal a wide range of skills while maintaining core firefighting capabilities becomes a measure of effectiveness. Training must be accessible and hands-on, blending classroom theory with field exercises that simulate chaotic, real-world scenes. In this sense, the movement toward multi-hazard rescue is not just an expansion of skill sets; it is a recalibration of the entire emergency response culture toward speed, coordination, and adaptability. The practical result is a service that can respond to floods, road crashes, chemical releases, and structural collapses with the same sense of urgency and the same commitment to life safety that has long defined firefighting.

The backbone of this transformation is structured training and standardized procedures that ensure consistent performance across diverse scenes. National or regional standards, such as those maintained by leading safety organizations, provide the framework for training curricula, certifications, and performance benchmarks. These standards translate into reduce risk for responders and increased likelihood of successful outcomes for those rescued. Training is not a one-off event but a continuous cycle of education, drills, audits, and real-world feedback. It spans initial recruit education, advanced rescue modules, and periodic recertification to reflect new techniques and equipment. The emphasis is practical: you learn the things that keep you and the public safe on a scene, you rehearse them until responses become almost instinct, and you integrate these capabilities with medical and environmental response for a coherent, reliable operation.

Within this landscape, the integration of protective equipment and toolkits stands out as a practical hinge between capability and safety. The ability to rapidly access trapped patients, stabilize unstable structures, or contain hazardous substances hinges on equipment that is fit for purpose and maintained to a high standard. Yet tools alone do not ensure success; they must be deployed within a well-communicated strategy that keeps the team oriented and the patient prioritized. The best brigades couple robust equipment with clear command structures, practiced handoffs to medical teams, and pre-planned engagement with other agencies. The result is an agile, credible response that can adapt to evolving conditions on the ground, from a tense water rescue to a delicate high-angle operation. This requires leadership that can read scenes quickly, anticipate complications, and coordinate the actions of a diverse team with discipline and empathy.

What does all this mean for communities and for those who serve them? It means that when the beep of a pager—or the alert in a dispatch room—signals danger, the responders who arrive first are not simply line fighters against one kind of hazard. They are a cohesive rescue system capable of protecting life across varied terrains and risks. Their training is a living map of the modern emergency landscape, a map that expands as new threats emerge and as communities grow more complex. It also means that public expectations extend beyond fire suppression to safe and effective rescue across multiple domains. In this reality, everyday citizens benefit from rapid medical interventions, timely extrications, swift water responses, secure high-angle operations, and rigorous environmental protections. The chapter on rescue operations by fire brigades, then, is really a story about how a disciplined, mission-focused organization remains relevant by embracing breadth without diluting depth. It is a story about people—trained and prepared professionals and volunteers—who choose to stand ready in all conditions so that lives are saved when seconds matter most.

A practical reminder of this integrated approach appears in hands-on training programs that emphasize the continuum from on-scene stabilization to transport. Education and practice become the currency of readiness, allowing responders to move fluidly among roles as the situation demands. The commitment to training is not theoretical; it translates into real-world outcomes, including faster on-scene medical care, safer extrications, and more effective management of environmental hazards. In this sense, the evolution of rescue operations is inseparable from the culture of the fire service itself—a culture that values courage, preparation, teamwork, and a relentless dedication to public safety. The result is a fire brigade that does not merely fight flames but also preserves life in the broadest sense, the very essence of emergency response.

For readers seeking a practical lens on how training and real-world practice intersect, consider the emphasis on hands-on skill development that underpins modern rescue work. As an example of the ongoing emphasis on field readiness, many departments integrate a variety of training formats, from controlled drills to live simulations. These experiences reinforce decision-making under pressure, the importance of role clarity on the scene, and the need for seamless cooperation with medical responders and municipal agencies. The narrative of rescue operations by fire brigades, then, is a narrative of continuous improvement—an ongoing commitment to expand the reach of protection while preserving and enhancing the safety of those who serve and those who rely on them. It is this dynamic, practiced, and people-centered approach that makes fire brigades indispensable in the era of multi-hazard risk.

Internal link note: for readers interested in the training dimensions that support this broad rescue remit, a detailed case of hands-on practice and tower-based drills can be found in the training-focused article firefighter training tower dedication. This resource underscores how dedicated facilities and structured programs contribute to the proficiency that modern brigades bring to every rescue mission.

External resource: for a broader framework on standards and best practices in rescue operations and emergency response training, consult the National Fire Protection Association’s guidance at https://www.nfpa.org/Code-Development/Committees/Committee-on-Fire-Prevention-and-Response/Rescue-Operations-and-Emergency-Response-Training. This external reference complements the chapter’s emphasis on training, certification, and standardized procedures that enable fire brigades to perform under demanding conditions while maintaining safety for responders and the public alike.

null

null

Beyond the Blaze: The Realities of Rescue Missions by Fire Brigades in a Multi-Hazard World

Fire brigades have long been associated with extinguishing flames and racing toward burning buildings. Yet over time, their mandate has broadened into a broader, multi-hazard emergency response framework. Today’s fire services—whether volunteer or professional—are commonly the first and sometimes the only organized responders to a spectrum of crises. In many regions, they routinely perform complex rescue operations that go far beyond firefighting alone. They extract people from wreckage after road traffic incidents, stabilize medical emergencies until clinical teams arrive, contain chemical spills, manage environmental hazards, and mount responses to natural disasters such as floods or structural collapses. This expanded remit is not simply a matter of added tasks; it reflects a shift in how communities rely on coordinated, rapid, technically proficient rescue capacity. The very nature of what counts as a rescue has grown to include creating safe access, stabilizing volatile situations, and ensuring the survivability of trapped or endangered individuals while preserving as much of the surrounding environment as possible. In this sense, fire brigades are becoming multi-disciplinary emergency response organizations whose success hinges on the seamless integration of training, equipment, and situational awareness across many different kinds of hazards.

To understand the rescue dimension of their work, it helps to consider the environments in which rescues occur. In the immediate aftermath of a crisis, whether in a crowded urban core or a secluded industrial site, the primary objective is not simply to reach a victim but to reach the right victim, preserve life, and do so with an approach that minimizes risk to both civilians and responders. Rescue operates on a continuum—from rapid triage and extraction to specialized stabilization and transport. The tools of the trade are diverse: sturdy protective gear, cutting and lifting devices, stabilization gear, medical supplies, and a range of access and egress tools designed to breach barriers, create safe routes, and maintain structural integrity as conditions evolve. While modern fire brigades use sophisticated techniques, the core principle remains the same: safety first, accuracy second, and speed third, all under the pressure of uncertain and often dangerous conditions.

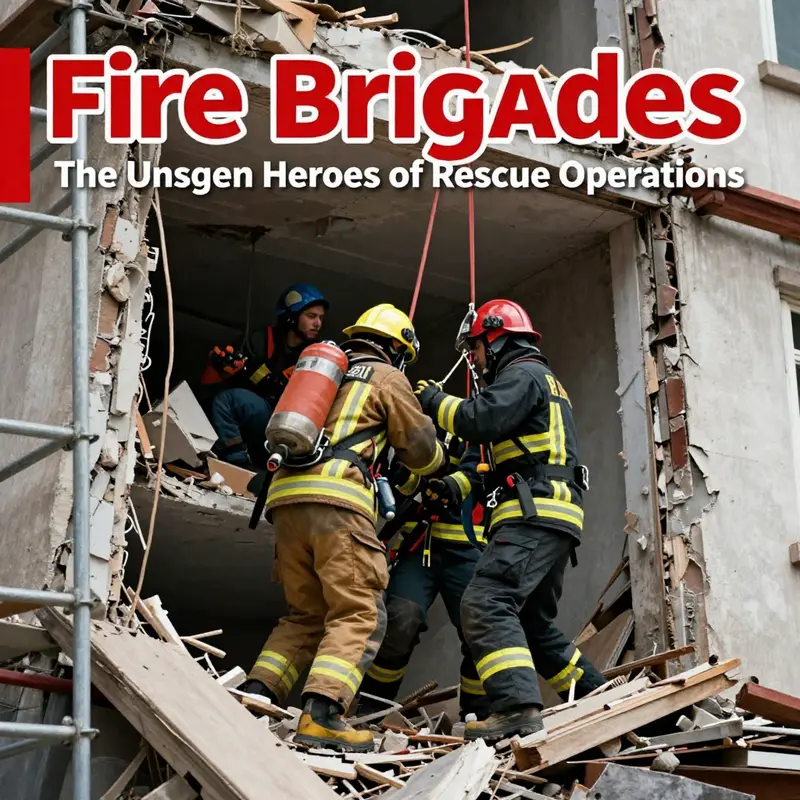

One of the most illustrative arenas for contemporary rescue work is the high-rise environment. High-rise buildings present a unique set of challenges that strain even well-prepared teams. The structural height creates persistent barriers to rapid access and egress, and the vertical distance compounds the physical demands of getting people out and bringing essential resources up. Elevators, typically a convenient means of transit, are generally unsafe or unreliable during emergencies, which forces responders and occupants to rely on stairwells. Those stairwells can become choke points for movement, smoke infiltration, heat buildup, and congestion. In such scenarios, the act of rescue becomes a careful choreography: securing the safest paths, prioritizing the most vulnerable individuals, and coordinating movement with minimal disruption to the flow of moving teams and equipment. The maze of corridors, floors, and stairwells demands not only physical stamina but acute spatial awareness, rapid decision-making, and the ability to adapt strategies as conditions shift with every breath of smoke or shift in fire behavior.

In these complex environments, communication is the lifeline of rescue work. Breakdowns in communication—whether due to structural interference, radio range limits, or the sheer scale of a multi-story building—can have devastating consequences. Frontline responders rely on clear, reliable dialogue with incident command, team members, and evacuees. Misunderstandings about locations, needs, or priorities can create dangerous delays and misdirected efforts. The colonial era adage about “seeing is believing” translates here into a modern imperative: responders must maintain uninterrupted channels to gather critical information, relay it to the right hands, and translate that information into actionable tactics despite unstable conditions. When the sounds of activity and urgency fill a stairwell, the ability to communicate calmly and precisely becomes as important as the mechanical tools at hand.

The physical demands of high-rise rescues also deserve emphasis. Rescue teams carry heavy equipment—breathing apparatus, cutting and lifting devices, stabilization systems, and medical kits—up multiple flights of stairs. The load bearing on a firefighter’s body multiplies the fatigue and decreases reaction time, especially when teams must maneuver through smoke, heat, and narrowed spaces. Fatigue affects coordination, situational awareness, and decision-making, creating a cycle in which recovery periods must be carefully balanced against the urgency of the rescue. Navigating confined spaces with limited visibility compounds the hazard, increasing the risk of slips, falls, and disorientation. These physical strains are not merely a matter of individual endurance. They influence the tempo of the operation, the sequencing of tasks, and the safety margins that responders must maintain while attempting to stabilize victims and safeguard themselves.

Compounding these physical and logistical hurdles is the often neglected factor of occupant preparedness. A key insight from rescue-focused research is that public education and regular drills can significantly reduce chaos during actual emergencies. When occupants lack familiarity with evacuation procedures or fail to respond promptly to alarms, bottlenecks proliferate, and the chance of successful extraction diminishes. Public drills are not a luxury but a critical operational asset that helps align civilian behavior with rescue teams’ needs. The synergy between trained occupants and responders can accelerate egress, reduce exposure to heat and smoke, and free responders to focus on technical stabilization rather than crowd management alone. This is especially true in high-rise environments where the density of people and the vertical complexity of the building can convert a routine alarm into a tense, high-stakes operation. Preparedness reduces panic, clarifies routes, and buys time—elements that often determine whether a rescue ends with a saved life or a tragedy.

Beyond the human dimension, the technological demands of modern rescue operations push fire brigades toward more integrated, real-time decision-making. Today’s rescues increasingly rely on advanced technology to assess conditions, coordinate actions, and visualize hidden hazards. Thermal imaging, for example, provides a window into the hot pockets of a building, revealing fire progression, trapped occupants, and structural weaknesses that would otherwise remain invisible. Drones offer vantage points that human teams cannot safely access, delivering overhead perspectives and helping incident commanders monitor fire spread, entrapment zones, and accessibility routes. Building management systems and connected sensors can supply continuous streams of data about structural integrity, gas concentrations, and environmental conditions, enabling responders to plan their movements in a data-informed manner. Yet the distribution of such tools is uneven. Some regions have the luxury of cutting-edge equipment and training pipelines, while others face resource constraints that limit their ability to integrate these capabilities into practice. The resulting disparity can widen the gap in outcomes across communities, underscoring the ongoing need for standards, shared protocols, and equitable access to lifesaving technologies.

The literature and field reports surrounding high-rise and multi-hazard rescues point to a core tension: the balance between rapid action and deliberate, methodical planning. The fastest path to a victim may not be the safest path for the rescuers or the building’s inhabitants if premature actions destabilize the environment. This tension is not a flaw but a fundamental characteristic of rescue work in volatile settings. Incident command must continually weigh the urgency of extraction against the risks posed by shifting temperatures, compromised structures, and evolving smoke movement. In practice, responders learn to adapt by staging operations, securing critical chokepoints, and implementing tiered rescue strategies. A staged approach allows teams to allocate resources where they are most needed, while still maintaining the flexibility to scale up or pivot as new information becomes available. The result is a dynamic, iterative process in which frontline teams and command structures converge to determine the safest, most effective sequence of actions.

The broader effort to support rescue operations also hinges on preparation, training, and standards. Fire brigades invest in ongoing training that covers not just firefighting techniques but also clinical emergency care, hazardous materials response, rope and water rescue, and structural stabilization. These competencies are reinforced through drills that replicate real-world conditions—dense smoke, uncertain access, distressed occupants, and the need to coordinate with paramedics, police, and utility personnel. The aim is to cultivate a shared mental model among responders so that, when a crisis erupts, every team member attributes a clear role and a common language to guide action. The importance of training is underscored by studies of high-rise operations, which highlight how proficiency in rescue techniques, calm communication, and the use of stabilization gear can dramatically improve outcomes in the most challenging environments. As rescue demands diversify, so too must the training regimes, ensuring that responders are equipped to handle vehicle extrications, medical emergencies, hazardous materials incidents, and natural disasters with equal composure and competence. In this context, emphasis on cross-disciplinary collaboration—bridging fire, EMS, hazardous materials, and urban search-and-rescue disciplines—becomes essential for sustained effectiveness.

Public-facing preparation and professional preparation intersect in meaningful ways. A robust rescue capability depends not only on what happens inside the firehouse but also on what happens in the broader community. Fire brigades often engage with local schools, workplaces, and housing authorities to promote fire safety awareness, evacuation planning, and protective behaviors during emergencies. These outreach efforts aim to demystify rescue operations and reduce chaos when alarms sound. For occupants, understanding their own role in a crisis—knowing how to move, where to meet rescuers, and how to report hazards—can dramatically reduce the decision time that rescues depend on. For responders, collaborating with civil authorities to ensure safe access routes, protective measures, and coordinated medical support helps create a more predictable environment for executing complex rescues.

The challenges identified in recent assessments of high-rise rescue operations are not merely theoretical concerns. They map directly onto the lived experiences of firefighters and rescue teams across the world. Limited access and the hazard of elevators are not abstract obstacles; they shape the entire planning process, from pre-incident surveys to on-scene tactics. Communication breakdowns are not mere annoyances; they can determine whether a team can coordinate a successful extract or become isolated under the weight of a collapsing stairwell. The physical demands of carrying heavy equipment through stairwells are not a test of endurance but a crucial limit that affects how teams allocate resources and how quickly they can reach a victim. Public education, drills, and the dissemination of practical evacuation guidance are not optional add-ons; they are essential elements of a resilient rescue ecosystem. Likewise, the technological dimension—applied through imaging, unmanned systems, and integrated sensor data—requires investment, standardization, and equitable deployment so that all communities can benefit from smarter, faster, and safer rescues.

All of these elements converge in a broader recognition: fire brigades perform rescue operations as a central aspect of their mission, even as the specifics of those rescues vary with context and hazard. The central question is not whether they can perform rescues, but how effectively they can do so under pressure, with the safety of civilians and responders as the top priority. This requires not only robust equipment and advanced training but also a culture that values preparedness, cross-agency collaboration, and continuous learning. When all these factors align, rescuers can translate the daunting realities of high-rise towers and other complex sites into outcomes that preserve life and reduce harm.

The debate about how to close gaps in high-rise rescue performance—whether through enhanced funding, broader access to cutting-edge tools, or expanded public education—must be grounded in evidence and guided by a long-term view of community resilience. It is about building systems that respond swiftly, reliably, and safely to a wide spectrum of emergencies. It is about recognizing that rescue work is not a narrow specialty but a core function of modern public safety. It is about acknowledging that every tier of the response ecosystem—from municipal planners to building managers, from training academies to neighborhood watch volunteers—has a stake in ensuring that when danger arrives at a stairwell, a corridor, or a doorway, the people inside and the people who come to help them can move with confidence and clarity. In this sense, rescuers are not only guardians against fire; they are stewards of a safer, more prepared community.

For readers seeking more practical guidance on building-ready training and preparedness that touches on the realities described here, consider exploring resources that highlight the value of dedicated training facilities and structured programs. These resources can offer concrete perspectives on how to translate classroom knowledge into field-ready competence and how to sustain a culture of readiness across teams and communities. For a deeper dive into the high-rise rescue challenges and best practices, see the external resource linked below. Additionally, ongoing professional development through specialized training modules and live drills remains a cornerstone of maintaining readiness for multi-hazard responses that involve difficult access, fragile occupants, and evolving threats. firefighter training tower dedication provides a window into how training environments are designed to mirror the complexities responders face, offering a practical touchpoint for those who seek to connect theory with on-the-ground rescue work.

External resource for further reading: for a comprehensive analysis of high-rise rescue challenges and recommended practices, refer to the International Association of Fire Chiefs’ technical report on challenges in high-rise fire and rescue operations: https://www.iafc.org/resources/technical-reports/challenges-in-high-rise-fire-and-rescue-operations

Final thoughts

The evolving role of fire brigades in rescue operations underscores their importance in enhancing community safety and emergency preparedness. As these brave individuals continuously adapt to new challenges and scenarios, their commitment to saving lives remains unwavering. A comprehensive understanding of their operations, training, and equipment not only highlights their capabilities but also emphasizes the need for ongoing support and resources to ensure their effectiveness in rescuing those in peril.