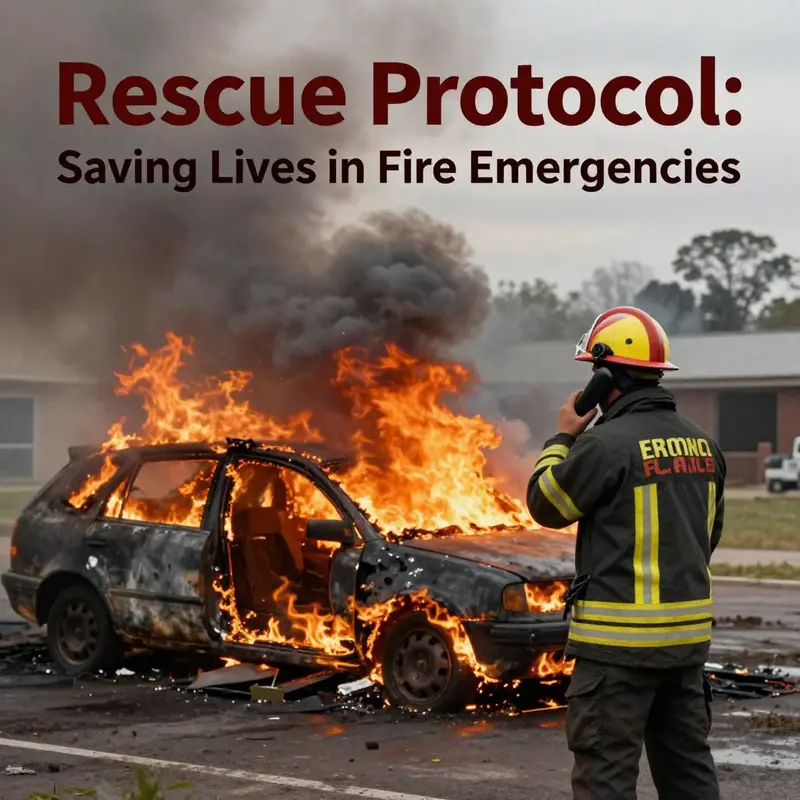

In the realm of automotive safety, understanding fire rescue techniques is crucial not just for firefighters but also for individual car buyers, auto dealerships, and fleet operators. Fires can erupt unexpectedly, particularly in automotive environments, making timely and effective rescue efforts essential. This article provides a well-rounded framework to assess situations, utilize effective methods for rescues, and avoid critical mistakes when faced with fire hazards. By addressing the unique needs of our target audience, we aim to empower readers with valuable insights to promote safety in fire emergencies.

Deciding When and How to Reach a Victim: Rapid, Continuous Assessment at a Fire Scene

Assessing a fire scene is an active decision-making process. Every second matters when someone is trapped. The goal is simple: choose actions that maximize survival while minimizing risk. That balance depends on clear, continuous judgment. This chapter explains how to form that judgment. It shows what to watch, how to prioritize, and when to act — or wait for trained teams.

Begin by recognizing that fire is dynamic. Flames, smoke, temperature, and structural stability change rapidly. Your first task is to determine whether a safe rescue path exists. Look for the shortest, most direct route to the victim that keeps both of you out of immediate danger. Shorter rescue times increase survival odds. That is a consistent finding across fire science and rescue modeling. Swift action matters, but reckless speed does not. The correct decision is fast and safe, not merely fast.

Assess visibility and smoke behavior first. Thick, fast-moving smoke often signals a lethal environment. Smoke contains toxic gases that can incapacitate a person in minutes. If you cannot see the victim or the route ahead, do not enter alone. Instead, call professional responders and relay precise location details. If visibility is limited but a clear path exists below the smoke layer, moving low and staying covered can enable a brief and controlled entry. Keep breaths shallow and cover mouths with wet cloth. A wet scarf or towel reduces inhalation of hot gases and particulates. Remember: smoke movement tells you where heat and fire are going. If smoke is drawing through a doorway toward you, that exit may still be viable. If smoke pushes away from you or pulses, active combustion is nearby and your route may close rapidly.

Evaluate heat and flame spread. Heat can destroy materials and cause flashover — a near-instantaneous ignition of an enclosed space. If you feel intense radiant heat from a doorway, open a door only a crack. Test for heat with the back of a gloved hand at the top of the doorframe. For civilians without protective gear, avoid opening doors into heavy heat. For trained rescuers, thermal imaging gives vital data. In all cases, timing matters: if heat is rising quickly, time-to-reach becomes a limiting factor. Rescue time must be short enough that you exit before conditions deteriorate.

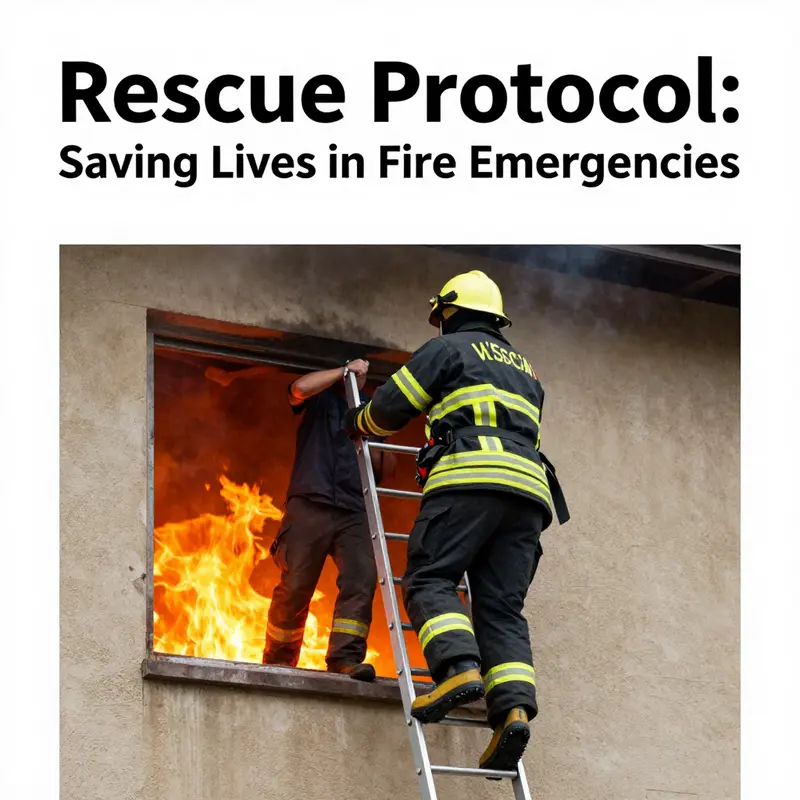

Consider structural integrity and collapse risk. Fire weakens support elements. Sagging ceilings, bowed walls, and cracked floors show danger. Look for signs of structural failure before you move a victim across a floor or plan a route via a stairwell. If a stairwell is heated, filled with smoke, or shows structural damage, it can trap you and the victim. In multi-story incidents, balconies and windows might offer safer access or egress — but only if those features are stable. When a building seems unstable, external rescue options such as aerial ladders, throw lines, or descent devices are safer choices.

Gather and use available building information. Every plan that shortens decision time helps. If you can, obtain a rough layout of the interior. Know where stairwells, corridors, and alternate exits are. In public buildings, this information is frequently posted or known by staff. For residential rescues, ask occupants where people are located and whether any interior doors lock. Fire suppression systems matter too. Active sprinklers or alarms likely slow fire growth and improve survivability. Their status should factor into your decision to attempt an entry. If sprinklers are operating, approaching may be less risky. If alarms are silent and sprinklers have failed, presume the fire has been burning longer.

Prioritize communication and coordination. Inform emergency dispatch of all visible conditions. Describe smoke color, density, flame location, and any structural changes. Give precise victim locations when known. This information allows arriving fire crews to prepare the correct resources. If other bystanders are present, assign roles: call emergency services, guide people to safety, secure a water source, or prepare basic rescue tools. Clear, simple instructions reduce duplication and confusion. If trained responders are on scene, follow their directions and provide all relevant observations.

Weigh the feasibility of external rescue. External options reduce exposure to smoke and structural hazards. Ladders, aerial platforms, and rope systems can reach windows and balconies. If one of these is available, use it. Even improvised measures like securely placed ladders can save time and reduce interior exposure. But always confirm that external anchor points are stable and that the device is rated or strong enough for the task. Improvised nets or cushions may help if a jump is unavoidable. Place mattresses, thick blankets, or foam pads below a window and keep them securely held. Communicate clearly with the victim: stay put unless instructed to move.

Decide on entry based on risk and training. Civilians should avoid interior rescues when heavy smoke, flames, or structural hazards exist. If you are trained and equipped, brief a simple rescue plan with your partner. Confirm who will carry tools and which path you will use. Select a designated retreat route and establish a time limit for exposure. If conditions worsen, abandon the interior and regroup. For untrained rescuers who determine entry is necessary, use basic protective measures: cover the body with wet clothing or bedding, move low, and keep to the shortest path. If you can see and reach the victim within a matter of seconds, a brief, controlled entry might be reasonable. If the victim is further away than a quick grab, the risk increases dramatically.

Understand the importance of time-to-victim. Research and fire models consistently show that survival decreases as time to reach the person increases. That is true for both heat exposure and smoke inhalation. Plan tasks that minimize that time. Position rescuers close enough to the hazard to reach the victim rapidly, but not so close that escape becomes impossible. Use staging areas near safe exits. Pre-position ropes, flashlights, and wet coverings to shorten the time between decision and action. If possible, place one rescuer to make contact and another to secure the exit and monitor communications.

Monitor ventilation and airflow. Opening doors and windows changes the fire’s behavior. Ventilation can remove smoke but can also feed a fire with oxygen. Before making openings, assess the likely effect. If possible, ventilate ahead of the victim to create a clearer path. For example, opening a window opposite the fire can draw smoke away from a rescue corridor. Avoid creating aerobic pathways toward areas with trapped people, unless you are confident that ventilation will not intensify flames. In many urban rescues, fire crews coordinate ventilation with attack teams. If you are alone, minimize unnecessary openings and focus on getting the victim out quickly.

Anticipate the victim’s condition and needs. A conscious, mobile person can often follow directions to self-evacuate. Use calm, simple commands. In loud environments, short phrases work best: “Stay low,” “Follow me,” “This way.” Try to keep the victim below the smoke layer and moving toward a clear exit. If the person is disoriented or physically limited, you will need help to carry them. Assess whether the victim is burned, airborne with toxic exposure, or likely unconscious. Unconscious people require immediate removal but may need stabilization to avoid spinal harm. For non-professionals, the priority remains removing the person from immediate hazard quickly and safely, protecting the airway and breathing where possible, and waiting for EMS for detailed care.

Use simple protective measures when moving through hazard zones. Wrap yourself and the victim in wet bedding or clothing if available. The moisture provides limited insulation against heat and prevents direct contact with embers. Move low and slow enough to avoid stumbling. If water sources exist, misting the environment can lower radiant heat and improve survivability. Carry a flashlight to maintain orientation and to signal to other rescuers. If an external resource can help, such as a garden hose or a wet blanket, deploy it to create a temporary protective corridor.

Pay attention to environmental predictors of rapid change. Flashover risk increases with rising temperatures and a sudden burst of thick smoke or roaring air movement. Wind can push flames into new areas, especially through broken windows. Rapidly spreading flame across the ceiling is an alarm signal. If you see these signs, withdraw immediately. Flip your assessment quickly from entry-capable to retreat. When in doubt, retreat. Lives are lost when rescuers become victims.

Coordinate with arriving professionals. When fire crews reach the scene, they will gather incident details rapidly. Provide them with everything you observed, even small specifics. Tell them where victims were last seen, which routes you used, and what makes and models of doors or locks might slow access. If you deployed external measures, describe them. If you have information about building systems, such as sprinkler activity or utility shutoffs, report those too. Good handover shortens their assessment time and reduces duplication of risk.

Use experienced judgment to form an exit plan before entry. Every practical rescue should have a pre-defined exit route and a time limit. Decide how long you will remain inside before withdrawing. Consider having a partner outside as a safety monitor. That person can call for help, pull you out if needed, and provide atmospheric updates. A two-person approach reduces the chance of getting trapped and accelerates response if conditions change.

Train and prepare ahead of emergencies. Regular drills sharpen the instincts needed for quick, safe decisions. Training includes reading smoke and fire behavior, practicing low-profile movement, and learning basic carry and drag techniques. These skills cut decision time in real events. If you want to grow skills, consider targeted courses on fire safety and rescue. Practical instruction matters, whether you are a building manager, workplace safety officer, or a concerned citizen. For those seeking formal development, resources on fire safety essentials certification and training provide structured, practical guidance.

Adopt a mindset of continuous reassessment. Every moment in a rescue alters the scene. As you move, watch for new smoke, sounds of weakening structure, or changing heat. Re-evaluate at each decisive point: entry, contact with the victim, and during the evacuation. If new hazards appear, switch to your retreat plan without hesitation. Continuous assessment is not hesitancy; it is an active safety tool that prevents small risks from becoming fatal.

Finally, balance courage with prudence. Stories of desperate heroism inspire, but they also show the cost of misjudgment. The best rescue is one that leaves both rescuer and victim alive and able to help in future incidents. Use the principles here to decide whether to act or call. Prioritize time-to-victim, maintain clear communication, and choose the method that preserves life without creating new casualties. Lives are saved when assessment, planning, and quick action combine.

For further reading on incident dynamics and case studies, see the recent report at China News: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/gn/2026/02-10/11538745.shtml

Calm Judgment, Courage, and Care: A Cohesive Path to Rescuing Someone from Fire Hazards

When a fire grows, the world around it narrows to a single, urgent question: can you help without becoming the next victim? The answer, in the most practical terms, begins with a quiet, disciplined mind. It does not demand heroism in a flash, but a measured blend of situational awareness, self-preservation, and an honest appraisal of what tools and routes actually exist. This chapter moves through that balance as a continuous narrative, tracing how a bystander might move from alarm to action, all while keeping the rescuer’s safety at the center. In real life, the difference between a successful external aid and a second catastrophe often hinges on the ability to slow down long enough to see the flames not as a single monster but as a changing map of danger and possibility. The first impulse must always be to breathe, to listen for alarms, to observe the direction of heat and smoke, and to ask the simple, stubborn question: is it possible to reach a person without placing myself in peril? If the answer is no, the right move is to evacuate and call for trained professionals who are equipped to enter the hazards with protective gear, breathing apparatus, and a disciplined plan. This is not neglect, but a prioritization that preserves the chance for future rescues. The principle echoes across established guidelines: safety is not a barrier to rescue but the roadway by which rescue becomes possible at all. As the smoke thickens and heat rises, it becomes clear that the only safe rescuers are those who accept the boundary between courage and recklessness and act inside it, using the scene as their guide rather than their fears alone.

From this foundation, the story of rescue unfolds in a manner that respects both the victim and the rescuer. When a fire limits visibility, when stairs or exits are blocked by flame or smoke, the path to safety narrows to a few stubborn options. The probability of success increases when one remembers the predictable patterns of fire behavior: hot gases rise, smoke obscures, and heat intensifies near the source. With this in mind, a responder does not chase the fastest impulse but chooses the safest route to help others outside the danger zone. The first duty, after all, is to alert others and ensure that emergency services are en route. The act of calling for help — whether dialing a local emergency number, broadcasting awareness through surrounding rooms, or guiding others to evacuate — becomes a vital part of the rescue that happens before any physical intervention. In many cases, this external action alone can save lives by reducing crowding and panic, creating pathways for professionals to operate, and keeping bystanders from stepping into the blaze themselves. A moment’s restraint at the threshold of danger becomes a lifetime of safety for those who must be moved later. The guidance central to this approach is clear: if you cannot safely reach someone without compromising your own safety, do not enter. Your personal survival preserves your ability to assist others now and in the future, when trained responders return with the equipment and the expertise necessary for interior operations.

When rescue moves beyond warning and alerting and enters the realm of physically reaching the victim, preparation remains the shared language between risk and relief. The situation dictates the rescue method, with the ultimate aim to transfer the person to safety with minimal additional harm. If stairs are blocked and exits are sealed by heat, a ladder or aerial platform becomes the preferred instrument of ascent. Fire ladders extend to windows, balconies, or rooftops where rescuees can be brought to a safer floor. In those moments, the scene becomes a choreography of lines and anchors. A throw-line gun can shoot a line to the trapped person, who then attaches a fire escape rope, a safety harness, or a personal descent device. Each of these tools carries with it not just a technical capability but a set of training and practice that must be observed for the operation to succeed. In multi-story structures, if equipment is unavailable or training is insufficient, it is prudent to avoid climbing unless there is explicit competency and proper gear. The risk of a fall or entanglement multiplies when an improvised approach takes the place of a trained system, and the cost of missteps can be measured in seconds and in the possibility of permanent injury. The scene’s safety is often a product of the resources at hand and the clarity of the rescuer’s plan.

In circumstances where someone is hanging from a window or balcony, another kind of tension emerges — the imperative to calm the person while arranging a safer descent. The rescuer’s voice becomes a lifeline: stay put, I’m coming, or we will be there soon. Where possible, a rescue net or airbag should be prepared below the person. Mattresses, foam pads, and even thick blankets can be deployed as makeshift cushions, though they are no substitute for certified equipment when the danger is extreme. The principle of avoidance remains central: never permit a jump unless it is absolutely the only viable option, and even then, ensure a controlled landing. For those who can walk but are panicked or confused, the guidance should be clear and reinforced: move low, stay below the smoke layer, and take each step with deliberate care. The rescuer’s instructions should be simple and repeated, such as “Follow me,” “Stay low,” and “This way.” The goal is to minimize panic and prevent a stampede that can injure more people than the fire itself.

For individuals who are unconscious or injured — burned or collapsed — the calculus shifts again. A rescue without full knowledge of the victim’s condition risks worsening injuries, particularly when spinal or burn injuries are present. The decision to carry must be weighed against the potential disruption to breathing, circulation, and trauma. If a carry is necessary, time-tested methods such as the fireman’s carry, the drag method, or a two-person lift provide controlled ways to move a person to safety. The technique is not merely a physical act but a procedural one: protect the victim with a wet blanket or fire blanket to shield against radiant heat and flame while moving through smoky air. In the heat of a fire, using damp fabrics reduces the transfer of heat to the victim’s skin, slowing the rate at which injuries worsen. It is essential to avoid synthetic materials that can melt and inflict further burns, and to maintain a steady, purposeful pace to prevent overheating both for the rescuer and the victim. If the feet and legs are the main point of contact with warmth, a blanket acts as a shield that buys seconds, which are often the difference between a survivable burn and a life-altering injury.

A critical technique that emerges across many rescue scenarios is to stay in contact with the ground, to move through the air near the floor, and to keep a continuous line of sight to the exit. The concept of maintaining a low profile in smoky environments is not simply a physical maneuver; it is a strategy for reducing exposure to toxins and heat. The air closer to the ground is typically cooler and less saturated with toxic gases than the air higher up, where heat accumulates and smoke thickens. The rescuer who keeps their mouth and nose covered with a wet cloth can filter some particulates and cool the air they breathe, making progress possible where others might retreat. The wet cloth or mask acts as a rudimentary but effective barrier, providing modest protection when a full respirator is not available. Movement through flame zones should be quick but not reckless. Wrapping both the rescuer and the victim in wet materials creates a thermal shield, reducing heat transfer during the critical passage through hot zones. If a water spray is available, a mist from a hose or fog nozzle can further cover the path by cooling the air and clouding the flames’ direct line of attack.

The chapter’s practical core rests on three intertwined threads: situational awareness, appropriate equipment, and clear, calm communication. The extent of one’s training becomes visible in every choice to use a rope system, a platform, or a ladder. A rope may be deployed with a throw-line gun to allow a trapped person to attach a safety line for descent, but only if the line is securely anchored and the user understands how to manage a descent device or safety harness. The rescue is as much about safeguarding the rope’s integrity as it is about the victim’s weight and balance. In situations where a person can walk but is overwhelmed by smoke or disorientation, guiding them to exit with gentle, precise commands turns potential chaos into an orderly evacuation. The rescuer’s voice, combined with visual cues and simple hand signals, can prevent confusion and reduce the chance of missteps amidst the commotion. The human element — empathy, patience, and steady presence — matters as much as any tool in the kit.

Beyond the moment of rescue itself lies the responsibility to protect the person who has just escaped danger. The chapter acknowledges a sobering truth through a real-world lens: direct interior rescues by untrained civilians carry substantial risk and can lead to fatalities. A powerful example from recent memory reminds us that the line between heroism and tragedy is fine and often unmarked until the moment has passed. The mother in Yunnan who shielded her child from a car fire exemplifies the courage that real life sometimes demands. Her act saved a life but cost her own, underscoring the principle that interior rescues must remain the domain of trained professionals whenever possible. This truth does not absolve bystanders from learning how to assist externally or how to call for help effectively; it emphasizes the need to prepare, to stay outside danger when necessary, and to use external tools and warning channels to the fullest extent. The takeaway for any reader is clear: knowledge is protective, but action must be aligned with safety, training, and the realities of the scene.

To anchor this guidance in practical, actionable steps, consider how a calm observer can integrate these principles into a single, coherent sequence. First, take a breath, then determine whether entering the fire zone is even remotely safe. If not, evacuate and summon help, guiding others to safety while maintaining order. If the path to a trapped person appears feasible with available tools, prepare a plan that includes a clear route, appropriate equipment, and a means of stabilizing the victim’s position. A rope, a ladder, or a device such as a safety harness could transform a dangerous crossing into a controlled descent. If someone is hanging from a window or balcony, the plan should foreground the use of nets or pads and a controlled lower or wait approach, avoiding a sudden leap. When a person can walk but is overwhelmed, offer a steady guiding hand, protect the airway, and encourage them to move with the lower, safer posture and the least resistance to heat and smoke.

As the narrative of rescue continues, it becomes essential to share the larger framework that makes these moments possible: the culture of safety. A culture that rewards rapid decision-making yet refuses to sacrifice one’s life for the sake of a single act—this is the culture that leaders and communities can foster through training, drills, and ongoing education. For readers seeking a structured path toward preparedness, there is value in formal instruction that addresses the specifics of fire safety and rescue. The link to related training resources offers a starting point for those who want to translate knowledge into capability. It is a reminder that individuals can contribute meaningfully to collective safety without stepping into harm’s way. The ultimate aim is to cultivate a public that understands the balance between courage and caution, where every person knows how to alert others, how to maintain composure, and how to engage the right tools at the right moment. This chapter therefore does not merely describe techniques; it invites a broader habit of readiness that strengthens entire communities against the unpredictable force of fire.

In closing, the practical synthesis of these lessons lies in a simple, enduring observation: the best rescue is the one that keeps the door open for professionals. Your survival preserves the possibility of future rescue and ensures that when trained teams arrive, they face a scene that can be managed with the full weight of expertise. The concepts outlined here are not a recipe for reckless daring but a framework for thoughtful, intentional action in the face of danger. They encourage us to respect the power of fire while acknowledging the limits of our control. They remind us to stay calm, to think clearly, and to act within the scope of our training, equipment, and the realities of the environment. And they invite you to take that next step toward preparedness by engaging with structured, practical training that can turn intention into capability. If this chapter has sparked a sense of responsibility, it is only because preparedness is a responsible choice that translates into safer outcomes when danger arrives.

For readers who want to explore further, practical training resources are available to support ongoing learning and confidence-building. As you continue to study and practice, remember that every skill you acquire adds another layer of protection for both you and those around you. The most important outcome is not the dramatic moment of a rescue, but the steady, reliable ability to respond with care, to protect life, and to reduce harm in the moments when danger is most acute. Your preparedness is the quiet force that enables safer rescues and strengthens the resilience of your communities. In this shared responsibility lies the promise that, even in the presence of fire, people can act with both courage and prudence to save lives while preserving their own.

Internal link for further preparation and structured learning: Fire Safety Essentials Certification Training.

External resource for official procedures: China’s Emergency Response Guidelines.

Courage, Not Recklessness: Critical Mistakes to Avoid When Rescuing Someone from a Fire

When we hear the crackle and see the smoke start to coil in the hall, the impulse to act is powerful. Courage in a fire is real and necessary, but it must be disciplined courage. The line between a brave rescue and a fatal misstep is thin, and the most important thing to protect is the life you intend to save and your own life as well. This is not a lecture on heroics; it is a reminder that certain missteps are so common they become almost cliché, yet each one carries a price tag in blood and pain. By understanding the critical mistakes that recur in rescue attempts, a bystander, a neighbor, or even an occupant can choose a safer, more effective path. The aim is not to extinguish fear but to channel it into judgment. The most reliable rule remains simple and unwavering: prioritize safety and rely on trained professionals when possible. Yet there are concrete errors people make that can be anticipated and avoided with awareness, preparation, and practice.

One of the gravest errors is stepping into a burning building without proper training or equipment. Smoke inhalation is a leading cause of death in fires, and even brief exposure can debilitate the strongest person. The human body loses its ability to think clearly when smoke fills the air, and in those moments the senses become unreliable. A rescuer without protective gear, particularly equipment such as a self-contained breathing apparatus, faces an arithmetic of risk: every second inside the burning space multiplies exposure to heat, toxic gases, and shifting structural integrity. The caution here is not a critique of impulse but a recognition that interior rescues are specialized operations executed by those trained and equipped to handle them. The safer choice, when you are not trained and equipped, is to stop, call emergency services, alert others, and direct people to evacuate. This is a moment where patience, clarity, and adherence to a plan can preserve life while buying time for professionals to arrive with the tools and training to conduct interior rescues.

A closely related mistake concerns attempting to extract a person through a smoke-filled or flaming route. Visibility in a fire is unreliable at best; heat and flames can render a path hazardous, forcing a rescuer to improvise under pressure. The instinct to reach someone who is visible through a doorway can be strong, but moving toward heat and smoke without a pre-identified, safe route is a high-risk choice. The safer alternative is to exit via a clear, pre-planned path or to guide the person to a safer location where conditions are more tolerable while awaiting professional help. If movement through smoke becomes unavoidable, low posture is essential—not just to stay under the smoke layer but to sense the environment with the hands before stepping into a new space. A door should be tested for heat with the back of the hand before it is opened, and every step should be taken with the understanding that the next barrier could be a furnace of heat, a sudden floor collapse, or a surge of flame behind you. In many cases, if there is no clear safe route and time is not on your side, the wisest choice is to slow down the retreat, keep the person calm, and wait for firefighters who can perform a controlled and safer extraction.

Another critical misstep is the failure to assess the situation before acting. The most common impulse is to rush toward the danger in a bid to rescue immediately, but rushing without information often makes things worse. Doors can become hot to the touch, floors can be treacherous, and a room that seems accessible can suddenly become a trap as fire grows or structural elements fail. The prudent rescuer pauses to scan for signs of fire spread, listen for distress in the walls or ceiling, and question whether the person is truly trapped or merely temporarily disoriented. A considered assessment includes determining if a safe exit exists, if a window or balcony offers a credible escape, and whether any equipment or external means could achieve a safer release. If a safe path does not present itself, it may be wiser to communicate with the trapped person, directing them to stay put if evacuation is improbable, or to move to a safer part of the building and await professional extraction. This deliberate approach reduces the likelihood of entering a zone where the rescuer could become another casualty, a scenario that often unfolds when fear overrides rational judgment.

Finally, attempting to carry someone out of a fire is a frequent but perilous misstep. The belief that a single, strong gesture can drag another person from danger is understandable, but it is seldom practical in a real fire. Carrying a conscious but injured person, or especially an unconscious one, slows you dramatically and increases fatigue, which in turn reduces your ability to navigate the hazardous environment. The old image of a hero carrying a person over the shoulder is powerful, yet in the chaos of a fire, it becomes a liability unless the rescuer is trained and the environment permits a controlled carry. If a rescue must be conducted, it is safer to use a drag technique with a blanket or clothing to minimize the victim’s movement and protect their body from heat. The body should stay as close to the ground as possible to keep away from the rising, hotter air near the ceiling, and where possible, an improvised shield—a wet blanket, a damp sheet, or a fire blanket—can offer precious protection from radiant heat. Even with a carry or drag in progress, the priority remains to shorten exposure time in the heat and smoke while moving toward a safer location where emergency responders can deliberate the next steps.

There is an element beyond technique that shapes outcomes: the choice of how to engage in rescue from the outside. The moment you decide to act from outside the danger zone, your focus should shift from trying to reach the victim to enabling the victim to exit or to guiding them toward a safe haven where they can be enveloped by safety measures and oxygen until professionals arrive. Calling for help is not passive; it is a deliberate and essential act that sustains the rescue effort, buys crucial time, and prevents the scene from deteriorating into chaos. When you are outside, you can also help by facilitating orderly evacuation, directing others away from danger, and performing basic checks on people who are safe enough to move. In many cases, the most effective form of rescue is ensuring others in the path clear out while you coordinate with responders, monitor conditions, and stay ready to relay critical information about the fire’s location, spread, and any changes you observe.

The practical lessons here revolve around preparation and training. Interior rescues are highly specialized maneuvers, and attempting them without the right equipment or instruction increases the likelihood of harm to both victim and rescuer. The principle is straightforward: Only enter if you have the training, the equipment, and a clearly defined exit plan. If any one of these components is missing, the safer, wiser course is to remain outside, call for help, and guide victims to the safest possible exit with calm, clear directions. This is not a sign of weakness but a recognition that stamina, time, and space are limited in a fire and that professional teams are trained to manage the most dangerous environments with protective gear, coordinated tactics, and safety protocols developed through years of field experience.

The narrative of rescue is one of balance—between speed and safety, between decisiveness and restraint. In moments of danger, a well-prepared person recognizes that action taken without guidance creates more risk than benefit. It is not a failure of courage to acknowledge this; it is an act of responsibility toward those who depend on you and toward yourself as a potential future rescuer who may one day need to rely on others. Those who want to improve their readiness can pursue formal training that focuses on essential safety principles, including how to operate at the edge of danger with a shield of knowledge. For readers who want to turn awareness into practical readiness, a cultivated habit of training and drills is essential. Such preparation does not erase fear but channels it into disciplined, deliberate action. Within the framework of responsible rescue, the path that preserves the most lives is the path that respects limits, plans the response, and uses the resources available—human, mechanical, and environmental—without stepping beyond what is safe to attempt.

To connect this awareness to action, it helps to reflect on the kind of guidance that has proven effective in real-world scenarios. For example, the disciplined approach advised by professional responders emphasizes the avoidance of interior rescues by untrained individuals, the use of controlled means to reach those who cannot escape on their own, and a strong preference for external assistance whenever possible. This perspective aligns with a broader safety culture that recognizes that the rescuer’s life is a resource that enables future rescues, not a solitary act of risk-taking. When a person recognizes this, the choices become clearer: call for help, assist from outside, and prepare to move with urgency but with methods that minimize risk. The emphasis on staying outside when interior entry is unsafe is not a concession to fear; it is a strategic statement about the value of life and the limits of improvised actions in a volatile environment.

The role of preparation cannot be overstated. Training in basic rescue principles, self-protection, and patient handling can make a meaningful difference. Those who actively seek to improve their readiness can benefit from resources that focus on core competencies such as safe decision-making, crowd control during evacuations, and the practical use of equipment like ropes, nets, or ladders in a controlled environment. The objective is to convert a surge of adrenaline into a clear sequence of steps that keep the rescuer alive and maximize the chance of the victim’s safe egress. In this sense, preparation is a form of quiet courage—an investment in calm, practiced responses that become second nature when the heat rises. It is also a reminder that safety protocols exist not to limit bravery but to extend its reach in the most dangerous circumstances.

The journey toward safer rescue behavior is ongoing. It benefits from a real-world understanding of what works and what does not, informed by data, training, and the collective wisdom of responders who have faced the most dangerous scenes. One practical takeaway is the value of learning to identify the safest exit routes in common buildings, rehearsing with others the steps to guide people to those exits, and ensuring that everyone knows the role each person can play in an emergency. Another takeaway is to remember that the moment of danger is not the moment to improvise new techniques; instead, it is the moment to rely on proven procedures, to stay composed, and to avoid entering environments that exceed one’s training or equipment. These principles are consistent with the broader aim of reducing harm and preserving life, both of those we seek to rescue and those who attempt the rescue themselves.

A final thread to hold onto is the ethical dimension of rescue work. Stories of heroism invite us to imagine a world where everyone acts instantly to save others. Yet the ethical imperative is tempered by prudence. People who act without proper training not only jeopardize themselves but may place additional burdens on emergency services that must then manage multiple victims. The aim is not to extinguish the impulse to help but to direct it in ways that are compatible with professional practice. This kind of guidance is not merely theoretical; it is rooted in the day-to-day realities that responders face, where the safest intervention is the one that reduces risk and preserves life through coordinated action. Those who are prepared to act, therefore, do so with disciplined caution, recognizing that rescue is a team effort—one that includes not only the person who leads the action but the many others who ensure a path to safety through communication, crowd management, and readiness to step back if conditions deteriorate.

For readers seeking practical ways to translate this understanding into everyday readiness, consider engaging with formal training that emphasizes safety and external rescue strategies. Training programs can increase your confidence in directing others to safety, reduce impulse-driven mistakes, and provide a framework for evaluating when interior entry is feasible. Such training can be combined with personal drills that simulate common fire scenarios in a controlled environment, helping to build muscle memory for when adrenaline is coursing and the clock is ticking. A stronger emphasis on the basics—staying outside, calling for help, guiding people to safety, and using protective barriers or blankets when moving victims through smoky areas—can dramatically improve outcomes. It is through this combination of knowledge, preparation, and prudent decision-making that we honor the courage to help while honoring the boundaries that keep everyone safe. If you are interested in building practical readiness, explore resources like the fire safety essentials certification training, which provides a solid foundation for responsible action in a fire emergency: fire safety essentials certification training.

In considering these points, it becomes clear that the most consequential victories in a fire are not dramatic last-second rescues but the consistent, low-risk decisions that prevent harm and preserve life. Real bravery, in the end, is the discipline to choose the safest option under pressure, to rely on professional responders for interior rescues, and to focus on getting as many people as possible out of danger while maintaining one’s own safety. This perspective aligns with the broader fire safety culture that emphasizes assessment, patience, and coordination over impulse and improvisation. As we continue to explore this topic across chapters, the thread remains constant: rescue is as much about preventing additional harm as it is about saving someone from immediate danger. Understanding and avoiding these critical mistakes is not a sign of hesitation; it is a sign of maturity and responsibility, a commitment to preserving life through informed, deliberate action. The path to effective rescue thus lies in the blend of courage, preparation, and disciplined execution, turning the heat of the moment into a controlled, life-affirming response rather than a gamble with fate.

For further guidance and to deepen your practical readiness, seek structured training that emphasizes safety in rescue operations and the realities of working with smoke, heat, and collapsing structures. Such training helps transform knowledge into confident and safe action when danger arises. And remember, the safest rescue is almost always the one that keeps the rescuer out of harm’s way while guiding others toward safety, letting professionals take the lead in the interior operations that require specialized equipment and expertise. The emphasis on safe, external action is not a denial of heroism; it is a realistic acknowledgment that in the most dangerous environments, the smartest, bravest choice is often to act decisively from the outside while waiting for trained responders to perform the interior work with the equipment and procedures that protect everyone involved.

External references and further reading can reinforce this mindset. For authoritative guidelines on fire safety and rescue procedures, refer to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), which offers comprehensive resources for the public and professionals: https://www.nfpa.org.

Final thoughts

Successfully rescuing someone from a fire requires not only immediate action but also calculated decisions rooted in safety practices. Individuals, dealerships, and fleet buyers must prioritize understanding how to assess fire situations, utilize correct rescue methods, and recognize critical errors to avoid. By cultivating a culture of knowledge around roadside emergencies, we contribute to safer environments for everyone involved.