Fires can occur without warning, endangering lives and property. This guide outlines crucial actions for individuals and businesses when faced with fire emergencies. Each chapter covers immediate responses, critical survival techniques, special scenarios, prevention best practices, and fostering safety awareness. Understanding these elements holistically prepares you to act effectively when fire emergencies arise, ensuring safety and potential rescue success.

In the Blink of Smoke: Immediate Actions That Make Fire Rescue Possible

When a fire erupts, the first breath you take after the initial shock becomes a decision point. The room brightens, heat prickles at the skin, and the clock seems to tick louder than your pulse. In that moment, panic is the enemy, but trained, decisive action is your friend. A few focused moves, performed calmly and quickly, can separate a tragic outcome from a survivable one. The chapter that follows is not a checklist crafted for a poster; it is a narrative of reflexes, training, and the kind of composure that only practice can forge. The aim is simple: to lay out the path from the earliest alarm to the safest exit—without getting trapped by the smoke, heat, or confusion that follow the opening flare of a fire. If you imagine yourself in the midst of a blaze, the path you choose must be clear, rehearsed, and adaptable to the environment you find yourself in. The immediate actions discussed here form the backbone of rescue and survival; they are not optional add-ons but the core of a sane, survivable response when every second counts.

First comes alerting others and evacuating. The instinct to protect others can surge with a moment’s notice, but the most important duty is to get people out as quickly as possible. When you discover fire, you shout a concise warning—“Fire!”—and move toward the exit with those around you. Do not hesitate to help others only if it does not delay your own escape. The door to safety is earned by simplicity: lead by example, move with purpose, and keep the exit route clear in your mind. Once you are outside and at a safe distance, call emergency services from a location that is not exposed to the danger you have just left. A telephone, even a cellphone, connects you to responders who can coordinate the correct resources for your building, your location, and the evolving situation. In some contexts, specific emergency numbers must be dialed; in others, general emergency lines will connect you to the right responders. The key is to prioritize a call from a safe place over any attempt to re-enter for information or belongings.

If the fire appears small and you have been trained to use a fire extinguisher or a reliable water source, you may try to suppress the flames—but only if it is safe and you can do so without delaying evacuation. The line between control and escalation is narrow. History and field experience show that a neighbor in Dehong managed to restrict a spreading blaze by utilizing a building’s internal hydrant to douse a refrigerator fire. That act, while commendable in a moment of quick thinking, was possible only because it did not compromise the evacuees’ exit or the safety of other occupants. In most situations, do not press forward with firefighting if the fire is growing, if the room is filling with smoke, or if you are not sure you can reach the source and return safely. When doubt arises, you step back from the flames and prioritize evacuation. The overarching maxim is simple: save yourself first, then assist only if you can do so without creating new risks.

The route to safety is determined by a careful assessment of your surroundings. Elevators are never a viable option during a fire. They can stall, lose power, or trap you between floors. Instead, move toward the stairs, the normal, tested artery to safety. If the stairwell itself is compromised by smoke or heat, you must improvise in a way that preserves your life. In such moments, retreat to your room and seal it off. Close the door, then block gaps under the door with damp towels or clothing to reduce smoke infiltration. Smoke climbs; air is precious; and every layer you add between you and the outside air buys time. Once you are sealed in, stay low and crawl toward any available ventilation, wall openings, or safe points that might offer a clearer path to the outside world. Your goal is to reduce exposure to toxic fumes while maintaining the ability to move if the path becomes available.

When you are able to move, the key is to choose a route that aligns with the wind and the structure’s layout. In many scenarios, this means heading toward the exit rather than away from the flames, especially in enclosed spaces where heat and smoke travel along the ceiling and concentrate in hallways. If you must traverse a room with visible smoke, keep to the floor. Breath through a damp cloth if you have one; stay quiet and focused so you can hear rescuers and follow their instructions once they arrive. The practical acts of staying low, moving deliberately, and validating the door’s temperature with the back of your hand before opening are not antiquated superstitions; they are proven, tactile checks that can keep you from stepping into a hot, deadly corridor. If a door feels cool, it may be safer to open slowly and survey the space beyond, while keeping your body close to the door and prepared to retreat if heat or smoke intensifies.

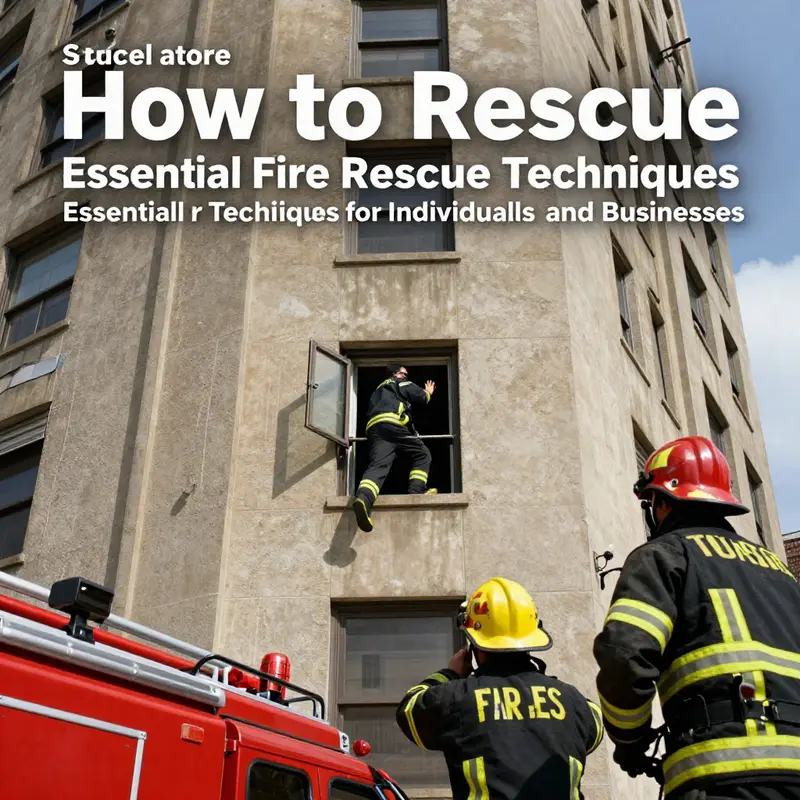

In the moment when the stairs are compromised, you might consider an alternative escape route, such as a window with a rope or a professional fire escape system, but these options demand caution. A rope fashioned from bed sheets or curtains can serve as a makeshift descent device if it is secured to something sturdy and if the ground below is forgiving—soft earth, grass, or a pile of leaves. The act of jumping from a height should be your last resort, kept for a height of four stories or less and only if no other corridor, stairwell, or window escape is viable. Even then, protect your head by tucking and rolling to minimize impact. The use of wet blankets or damp clothing as you move through flames is another measure that can reduce radiant heat exposure and buy precious seconds. These steps, while seemingly improvised, are grounded in the realities of fire behavior and human physiology, where heat and smoke can overwhelm in moments and the safest choice is often the most direct path to outside air.

Sometimes the path to safety is not to escape at all costs but to retreat to a haven where help can reach you. If you cannot leave the building, you should find a safe room—the bathroom or a bedroom with a window is ideal. Shut the door tightly and seal cracks with wet towels or sheets to prevent smoke from leaking in. Keep the door closed to slow heat transfer and use a flashlight or a bright cloth to signal responders at the window. This retreat-to-safety approach is not a sign of surrender; it is a calculated move to create an accessible beacon for rescue teams. It is a practice in rational restraint: do not sacrifice your safety to try to rescue others without proper equipment or a clear plan. This mindset—prioritize survival, then assist—saves lives and reduces the risk of creating additional victims.

There are hard boundaries to any rescue effort in a fire. Never jump from a height without considering the fall conditions and the availability of a soft landing; never venture into a burning building to extract someone without the necessary training and equipment; never assume that others will find their own way out when it would be quicker to guide them to safety yourself. These boundaries are not limits on courage but guardrails for safety. When someone is trapped, your best contribution is to alert emergency services with precise information about location and conditions, while maintaining your own safety. Rescue requires a coordinated effort, and professional responders rely on accurate, timely information to prioritize actions and allocate resources.

Preparation matters, too. The topmost risk-reduction strategy is prevention: working smoke alarms, clear exits, and family escape practice. Yet even with these measures in place, real-world fires demand a distinct, practical response. This is why the habit of rehearsing your escape route, strengthening your verbal commands for family members, and maintaining calm under pressure matters. A trained mind defaults to action even when the body trembles, and that is exactly the bridge between fear and survival. For individuals seeking to deepen their understanding and readiness, there are formal avenues of learning that can sharpen judgment under pressure. The Fire Safety Essentials Certification Training is one such resource that aligns with practical, field-proven principles. It presents core concepts—alarm recognition, evacuation prioritization, and safe communication during emergencies—in a structured format that translates to real-world behavior when a fire starts. This kind of training helps you internalize the right questions to ask and the best channels to rely on when seconds count. If you want to explore such resources, you can find more details at the related program page.

In the broader arc of rescue and survival, the narrative is not merely about knowing what to do; it is about turning knowledge into practiced reflex. This requires drills that reflect the realities of your living environment. It means walking through your home with a flashlight at night, planning two or more exit routes from every room, and rehearsing the steps to seal a room if the path to safety is compromised. It means teaching children not to hide from fire but to move toward the nearest exit and call for help. It means understanding that while a neighbor’s or a stranger’s quick actions can alter the outcome, your own actions must be reliable, repeatable, and quick. The best rescue is one that begins with the person closest to danger and ends with responders who can take over with trained procedures. It is a continuum of awareness, preparedness, and calm, even when the air grows thick with smoke and fear.

The practical lessons extend beyond a single incident and into a culture of safety. Building owners and occupants should foster environments where exits are always accessible, doors are never blocked, and paths to safety are clearly marked. Regular drills keep the memory of flight routes fresh, ensuring that orients people to the fastest, safest means of egress even when visibility is compromised. In such a culture, the phrase “stay low and move fast” becomes more than a slogan; it becomes a lived habit that translates into seconds saved during a real event. The human factor remains central: air, heat, and smoke will bend around you, but a clear mind and a practiced sequence can push you toward safety while protecting others.

For readers who want to deepen practical understanding while maintaining the narrative of rescue in action, consider the available resources that focus on safety training and preparedness. The knowledge embedded in real-world responses, including the account from Dehong, emphasizes the importance of swift evacuation, the prudence of using fire suppression only when safe and feasible, and the value of clear guidance for rescuers who arrive later. These insights remind us that while no one can eliminate danger entirely, trained reflexes, calm decision-making, and coordinated responses dramatically increase the odds of survival. The central message remains consistent across contexts: the most effective rescue begins with staying calm enough to think, acting quickly enough to exit, and preparing for the moment when help arrives. The aftermath—injury, loss, or recovery—depends on how effectively you translated knowledge into action when it mattered most.

External resource for further reading: https://www.sohu.com/a/748267011_120329

Fire Safety Essentials: Quick Action to Survive a Fire

At the first sign of fire, act with purpose. Alert others, exit, and call emergency services from a safe location. Maintain calm to improve decision making. As you move, stay low to avoid smoke and cover your nose and mouth with a cloth when possible. Test doors for heat before opening; if hot, do not open. Use stairs, not elevators, and keep close to the wall to feel the path ahead. If you are trapped, seal gaps with damp towels and signal for help through a window or door. Practice a home escape plan with two routes from every room and ensure working smoke alarms. Regular drills strengthen reflexes and reduce hesitation when seconds count. After escaping, stay outside and keep others safe while emergency responders arrive. For ongoing readiness, seek credible fire safety training and certifications to translate instinct into reliable, practiced actions. External resources and official guidance can support preparedness, but the core habit remains clear: alert, exit, and seek help quickly and safely. Remember, never re-enter a burning building, and keep exits clear. These habits form the foundation of personal safety and community readiness.

Special Situations in Fire Rescue: Navigating High-Rises, Forests, and Trapped Moments with Calm, Strategy, and Survival

When fire erupts in real life, the environment often diversifies the risks far beyond a simple room full of flames. The same core principles—breathing, staying low, and moving with a plan—remain vital, but special situations demand a disciplined composure and a flexible strategy. The scene may be a towering building where stairs replace elevators as the only reliable escape, or a wild landscape where wind, terrain, and fuel sources push the fire in unpredictable directions. In each case, the objective stays the same: reach safety while reducing exposure to heat, smoke, and structural collapse. To move through these threats with confidence, it helps to anchor your decisions to a few unwavering habits. First, lower your center of gravity and crawl when possible. Heat and smoke rise, so the air near the floor stays cooler and less toxic. Second, protect your airways with a damp cloth or layered fabric, and keep that protection within easy reach. Third, never abandon caution for haste. A hurried rush through a doorway or stairwell can trap you or funnel you into a hazard. In special situations, calm, deliberate actions become your most valuable tools, and the choice between a window, a stairwell, or a less obvious exit can determine whether you live or die.

In a high-rise setting, the dynamics change in ways that can feel counterintuitive. The vertical distance to safety can seem daunting, and the pull of a downwind exit may not always be available due to smoke banks or fire progression. The most trusted rule remains the staircase, never the elevator. Elevators are vulnerable to power failures and mechanical malfunctions during a fire, and they can strand passengers or expose them to extreme heat from shafts. If the stairs are clear, use them while staying close to the wall to preserve orientation. If smoke blocks a stairwell or doors appear dangerously hot, retreat back to your room and close the door, sealing gaps with damp cloths or sheets to slow smoke infiltration. A closed door becomes your barrier against the flame front and the toxic load of the environment outside. In such moments, signaling for help becomes as important as moving toward safety. From a window, you can draw attention with bright clothing or a flashlight and call emergency services if you have a phone with you. The window can become a legitimate escape route if all other exits are compromised, but the decision to use it should be careful and deliberate: only attempt window escape if you are confident you can reach a safe landing below and if you have a secure means to descend. Where a rope or a fire escape ladder is available, it should be used only if you are trained and confident in securing it. In planning your actions, you might recall the cautious approach of testing doors before you open them. If a door feels cool to the back of your hand and the knob is not hot, you may slowly open it, scanning for heat and smoke beyond. If the door is hot, you seal it again and seek another route. This small check—door temperature before opening—can spare you from a flashover or a sudden fire blast that traps you between flames and a sealed room.

In forested or wildland settings, the rules shift again because the fuel is vegetation and the heat is often driven by wind patterns rather than walls. Here, the principle of escaping with the wind remains critical; moving upwind of the fire is often safer than moving downwind into its path. If you are caught and surrounded by flame, remember that fire tends to move uphill faster than downhill; descending toward lower ground can reduce immediate exposure to heat. If you must shelter, seek a natural or man-made clearing that can act as a firebreak and lie flat, covering exposed skin with damp cloths if available. The aim is to create a break between you and the flames while allowing cooler air to circulate near the ground. In some circumstances, you may contribute to fire containment efforts only if you have proper training and equipment. Personal action that involves attempting to burn off brush around you, or to create a new burn line, can be dangerous without professional oversight, and it is generally prudent to prioritize self-rescue and the clearance of a safe exit from the fire’s edge.

A central theme across all special situations is how you manage the moment you realize you are trapped or unable to evacuate immediately. Do not leap from windows unless you are certain you can reach a safe landing. If you are within a room that cannot be entered or exited, place yourself near a window or ventilator where you can be seen and heard, keep your head low to the floor where air quality remains better, and stay hydrated if you can. Use a cell phone or other signaling device to call for help and to describe your location clearly. Describe nearby landmarks, floor numbers, stairwell arrangements, and any doors or windows that could act as beacons for firefighters. In many jurisdictions, official rescue protocols emphasize coordinated, professional intervention. Firefighters bring specialized equipment and training to perform rescues that civilians cannot safely execute. Their intervention can involve controlled entry through doors, strategic cutting, or rope-assisted descents. In moments when a property is structurally compromised or the fire movement is unpredictable, cooperating with rescue crews and following their instructions is essential. Even when you can see the exit, do not rush into a hazard that may still be actively burning or structurally unsound. The ideal outcome is to be found by responders rather than by your own attempt to re-enter a dangerous zone.

The specifics of when to use a window for escape or signaling cannot be overemphasized. In a high-rise, if stairwells become blocked, signaling from a window becomes a critical option. The act of signaling should be deliberate and visible: use a bright cloth or clothing to attract attention, wave with a steady rhythm, and keep movements to a minimum to conserve energy and preserve your ability to breathe. In a forest fire, the decision to stay low near a breath of clean air may also involve signaling for help with a whistle or a phone call that can guide rescuers to your precise location. The common thread in these choices is situational awareness—the ongoing, real-time assessment of wind direction, heat, smoke density, and your own energy reserves.

Within the broader ecosystem of rescue and safety, special situations also demand prudent limits on who should attempt rescue or self-rescue. If you encounter someone who is trapped, your first duty is to alert emergency services and provide precise information about the person’s location and condition. Do not attempt to enter a burning building to retrieve someone unless you have the appropriate training, equipment, and a trained partner. The instinct to help is powerful, but the risk of becoming another victim can overwhelm the initial intention. The professional rescue teams are trained to operate in environments where the balance between life and death rests on exact timing and controlled risk. They may use equipment that can safely breach walls, create controlled ventilation, or execute a rescue from positions of relative stability. Recognize the value of their expertise and allow them to work under established protocols. It is this coordinated teamwork—between civilian self-help actions and professional operations—that anchors the most effective rescue outcomes in special situations.

Another layer of complexity arises from the practical realities of reporting and seeking help. In a fire emergency, the number one priority is safety, not precision in language. If you have a mobile phone, maintain a calm, concise description of your location, the nature of the fire, and any hazards you can observe. You may need to stay on the line with a dispatcher while you implement your escape plan, especially if you are in a position where the path to safety is unclear. The guidance on when to contact emergency services is explicit in many official sources: do not call for a fire that you know is not occurring or that is under control, to avoid tying up resources, yet do call promptly when a genuine fire or life-threatening condition exists. The balance between proactive self-help and the restraint that preserves emergency resources is a delicate one, but it is at the heart of effective behavior when situations become tense and uncertain.

In keeping with the broader emphasis on preparedness, the real power of these special-situations guidelines lies in their integration with ongoing training and practice. Principles learned in formal courses—how to assess heat through a door, how to crawl with a damp cloth, how to check exits before opening them, and how to signal for help—become automatic under pressure. This automaticity turns potential chaos into a sequence of steps that you can perform without hesitation. It is the kind of knowledge that resonates with the idea that prevention and preparation save lives. The more familiar you are with your own environment, the faster you will be able to identify the safest routes and the more quickly you will recognize when a route has become unsafe. That is why a culture of safety—grounded in rehearsed escape plans, properly functioning alarms, and a readiness to adapt to changing conditions—appears repeatedly in expert guidance as the most resilient response to any fire scenario, including the most challenging special situations. For readers seeking practical reinforcement of these ideas, the concept and practices highlighted in fire safety essentials certification training reinforce the real-world application of these principles. fire safety essentials certification training.

As you carry this knowledge forward, remember that even the most competent person can face moments when the safest action is to wait for rescue. Do not underestimate the value of remaining in a secure location and signaling for help if you are uncertain about your ability to move through smoke and heat. The aim is not bravado but survival, and the fastest way to achieve safety is to align your behavior with a well-practiced plan and the guidance of trained professionals. In the larger arc of fire rescue, special situations compel us to adapt, to think clearly under pressure, and to cooperate with responders who have the tools and authority to reach us. The repeated message across all these scenarios is simple: stay calm, move deliberately, protect your airways, seek the safest route, and call for help when appropriate. In doing so, you maximize your odds of a successful outcome and minimize the risks that arise when conditions abruptly change.

External resource for further reading on specialized procedures and official protocols can be found here: https://scjg.beijing.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgkml/ajxx/202506/t20250609_3813918.html

null

null

Awareness as Armor: Building Safety Consciousness and Rescue Readiness When Fire Strikes

In a fire, awareness is not a luxury. It is a lifeline that travels ahead of fear, guiding choices when every second could matter. The core principle—Prevention First, Response Second—remains a compass for every person caught in a blaze. When you understand that staying alert, moving deliberately, and acting with a plan can shape outcomes, you begin to treat safety as a practiced habit rather than a reactive impulse. This mindset, emphasized by seasoned authorities and echoed in regional safety programs, hinges on the simple truth that the essence of fire safety lies in people. Each person becomes a line of defense, a link in a larger chain of readiness. The chapters that precede this one have laid the groundwork: know the route out, keep exits unobstructed, and maintain devices that alert you to danger. Here, the emphasis shifts toward translating that knowledge into immediate, practical action when smoke curls through a hallway or a flame gnaws at a doorway.

The first moment of action is the hard one to master: calm. Panic drains perception and narrows options. A deliberate breath, a quick scan of your surroundings, and a mental map of exits and wind direction can keep you out of a trap. Look for the nearest stairwell, not the closest object of comfort. The wisdom of the Golden Rules is not rhetoric; it is a disciplined habit. If you see flames or heavy smoke, your priority is to move, not to investigate. In a building, the stairs are your ally; elevators are not. This distinction forms a core part of any survival mindset and should be rehearsed as part of family drills, workplace safety plans, and community training.

As you begin to move, the question becomes how to evacuate without becoming another casualty to smoke or heat. The air in flames-filled environments is more toxic than the flames themselves. Therefore, protecting your airway is the immediate objective. A simple cloth—damp if possible, dry if not—can filter some particles and keep you from inhaling hot gases. The cloth acts as a shield for the nose and mouth, but the technique matters: don’t fray through the smoke by standing upright. Stay low, crawl if possible, and keep your head protected. Smoke travels upward; the cleaner air hugs the floor. Every step should be deliberate, with an eye on potential changes in the environment—like a door that suddenly swells with heat or a hallway that fills with heat from behind a closed door.

When doors block your path, the test is to check first for heat. Touch the doorknob and the door’s surface with the back of your hand. If heat returns the touch, the fire is nearby. Do not open such a door. The alternative path could be through another exit or toward an area that offers shelter while you wait for rescuers. If you must shelter, sealing off the room with damp towels under the door and around cracks can buy precious minutes by slowing the spread of smoke. This is not a permanent solution, but it is a stopgap that preserves breath and reduces exposure until help arrives. In the most challenging moments, signaling becomes vital. If you are trapped and hope to be found, draw attention with visible signals—bright cloth at a window, a flashlight, or a mobile screen held high. Pair this with a loud, steady call for help. The “high and loud” approach, recommended in case studies from academic settings and firefighting academies, increases the odds that rescuers outside will hear you and locate your position in a smoke-blanketed environment.

A crucial aspect of early rescue is understanding the scope of the threat and acting accordingly. If the fire is small and a clear escape route exists, evacuate immediately and do not waste time on belongings. The discipline of prioritizing life over possessions is a constant theme across fire-safety guidance. Once you are safely outside, call the emergency number in your region and provide precise information: your location, the nature of the fire, its size, and a contact number. Do not hang up until the operator confirms they have the details. This step, simple yet essential, ensures responders can deploy efficiently and coordinate with on-site civilians who may be able to guide teams to trapped individuals.

Beyond the immediate act of leaving a room, mindful decision-making about the path you choose can influence your safety dramatically. In some circumstances, moving against the wind is advantageous, especially during outdoor wildfires. In a building, the aim is to reach the exit that offers the clearest air path and the least resistance from smoke and heat. If stairs are rendered unusable by smoke, consider alternative routes that lead you toward a safer ventilated space or a window that can serve as a last resort escape. When windows become the only viable option, do not rush headlong through an opening that might be compromised. If you must descend to a lower level or contemplate a window jump, keep in mind the four-story guideline: jump only to ground that is soft and forgiving, and protect your head during the descent. Even in a contained structure, using a rope or a ladder built from sturdy fabrics may be appropriate if it is secured by a reliable anchor and you have the training to use it.

In the event that a direct escape is not possible, sheltering in place becomes the alternative. This is not surrender; it is a calculated choice built from the understanding that a highly trained team with equipment can reach you more effectively than a poorly prepared solo pursuit through a hostile environment. If you are trapped in a high-rise or interior pocket, close doors, seal cracks, and signal for help. The window can become a beacon for responders, and the room may offer a containment zone where you conserve air and limit exposure to heat. The knowledge that you are not alone—emergency teams are moving toward you with specialized gear—can shape your actions and reduce panic. In the right moment, you might be required to maintain contact with the outside world, providing updates on your location and status to assist rapid rescue.

These principles extend beyond the walls of a single building. The deeper training that makes a difference in real-life rescue scenarios comes from practice and community investment. In high-rise settings, for example, the ability to relocate to a safe room and signal for help has saved lives when stairs become compromised or blocked by smoke. In rural or forest environments, the risk calculus shifts again: uphill fire tends to outrun downhill paths, and the terrain may demand differently timed decisions, such as creating a temporary firebreak by starting a controlled burn away from your location—an option only under specific conditions and with appropriate training. The purpose of these guidelines is not to overcomplicate choices but to empower you to make fast, reasoned decisions when fear is at its peak.

The broader picture—prevention as the ongoing work of safety—remains central. Smoke alarms should be installed on every level and inside bedrooms. Exits must be kept clear, and escape plans practiced regularly. When neighbors collaborate, the outcomes improve dramatically. A well-informed community reduces the time it takes for help to arrive and increases the likelihood that people can evacuate in an orderly fashion, guiding others along the safest path. The value of collective preparedness has been demonstrated in various regional incidents, where trained bystanders who remained calm performed critical interventions, evacuated others, and aided responders by providing precise spatial information and facilitating early access for firefighters. The simple act of maintaining clear pathways, reporting hazards, and practicing drills can transform a potentially chaotic scene into a coordinated operation with fewer casualties.

As you reflect on these ideas, consider the responsibility of ongoing education. Fire safety is a continuous practice, not a one-time event. Regular drills, periodic checkups of alarms, and the reinforcement of escape routes in homes, schools, and workplaces anchor a culture of readiness. It is easy to underestimate how small habits—checking doors for heat before opening, keeping exits unobstructed, and ensuring everyone knows the emergency number—combine to create a robust defense. The people who excel in emergencies are those who train when there is no smoke, who rehearse their responses until the actions feel almost automatic. In this sense, awareness becomes an instrument of resilience, a shield formed by knowledge, practice, and a willingness to prioritize life over convenience.

For those who want to deepen practical understanding and gain structured, hands-on capabilities, training resources that emphasize safety fundamentals, rescue protocols, and scenario-based learning can be invaluable. The most effective path to competence blends classroom theory with real-world drills, ensuring that reactions are reflexive rather than hesitant. A strong emphasis on certification, ongoing practice, and community involvement helps transform individuals into capable responders who can support others while awaiting professional help. To explore a practical, competency-building path, see the resource titled Fire Safety Essentials Certification Training. This training emphasizes core skills, safety awareness, and the disciplined approach that underpins successful rescue efforts without compromising personal safety.

Ultimately, the best safeguard against fire danger is a proactive culture of prevention and preparedness. The knowledge to stay calm, to move quickly and safely, to protect airways, and to signal effectively is a toolkit you can carry with you everywhere you go. It is a mindset you can cultivate at home, at work, and in your community. The more consistently you apply these principles, the more you reduce risk not only for yourself but for those who rely on you. The chapter you have embarked upon is not merely a compilation of rules; it is a call to adopt a practiced, shared approach to safety. When every person understands their own role as a first line of defense, rescue becomes less about heroic moments and more about a coordinated, deliberate, and humane response to danger. That is the essence of rescue in fire: awareness that translates into action when it matters most.

Final thoughts

In summary, being prepared for a fire emergency is not just a necessity; it’s a responsibility. From understanding immediate actions to applying critical survival techniques, each element is vital for ensuring safety. Equip yourself and your organization with knowledge and skills, embrace prevention strategies, and foster safety awareness to protect against potential disasters. Awareness and preparedness are key to resilience in face of fires.