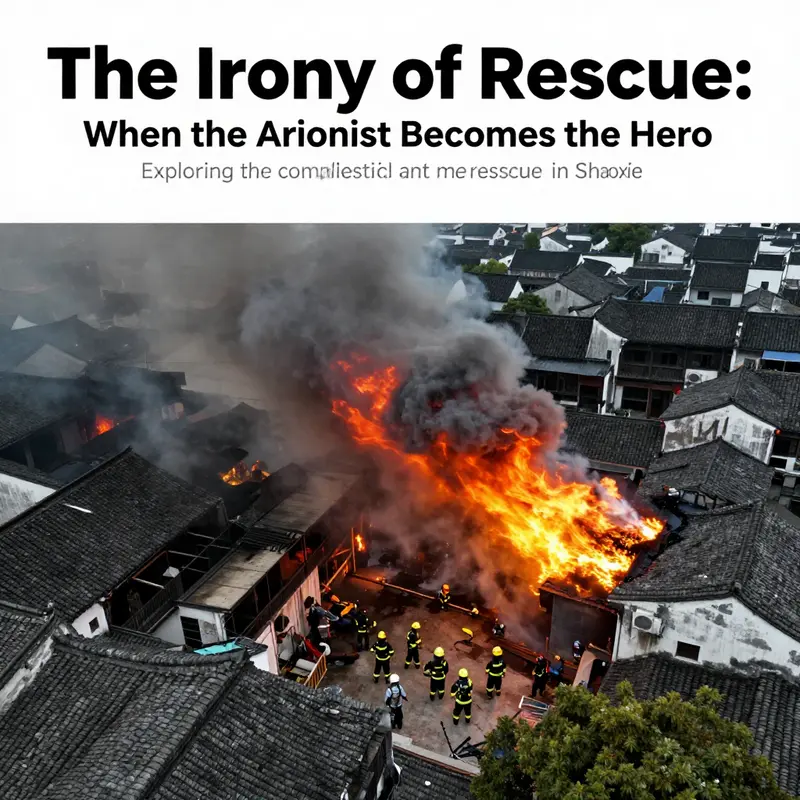

The phenomenon of individuals becoming both the source of a crisis and the unlikely heroes in its resolution is a perplexing aspect of human behavior, as seen in the recent incident in Shaoxing City’s Yuecheng District. This tragic irony unfolds in the form of a fire sparked by a self-proclaimed hero, who, in a misguided attempt to assist, turned out to be the very person responsible for starting the blaze. The investigation into this shocking case prompts a deeper examination of the underlying motivations behind such actions, as well as the immediate and long-term consequences faced by the community and emergency services. Each chapter of this article will dissect varying dimensions of this incident: the irony of the arsonist’s dual role, an analysis of motivations driving them, and the broader implications on public perception and response from emergency services as they navigate the complexities of such emergencies.

The Irony of the Flame: How a ‘Heroic’ Bystander Sparks Rescue and Unravels in Shaoxing

If you walk into the memory of a public blaze with the mind of a storyteller, you will hear two voices at once. One is loud with alarm, the other soft with intention, both echoing across a scene where fear and certainty are mutually exclusive until the smoke clears. In Yuecheng District, Shaoxing, at the heart of a modern complex known as 1051 Creative Park, a chorus of voices emerged as a fire took hold. Onlookers described a man who moved with a blend of urgency and composure, a figure who appeared to pull strangers toward safety while simultaneously pulling the scene into a kind of moral drama. He shouted for help, directed people away from danger, and organized a makeshift line of improvised responders. He wore the uniform of a citizen-hero, not in any official sense but in the public imagination: the kind of bystander who seems to grasp the right action in a moment of crisis. It was a narrative that fit neatly into a social need for clarity in chaos. Yet as the investigation unfolded, that exact frame of action dissolved into a different truth: the supposed hero was the one who started the fire, a bystander who had intended not to save but to signal something far less noble. The case became an irony that was cruelly precise, a demonstration that in emergencies, the most instinctive impulse—to act, to be seen acting—can disguise another motive entirely. The very spark that summoned a rescue brought into focus a paradox that has haunted fire lore for generations: the line between saving lives and endangering them can be paper-thin, and the hero of one moment can become the hazard of the next. The public memory of that day, though, does not hinge on the simplest refrain of heroism or villainy. It rests in the tension that the event exposed about human behavior, about how communities interpret risk, and about how the media and authorities translate act into motive when the dust has settled and the investigative notes are laid open for scrutiny.

To understand how a fire can conjure a rescue and yet be authored by a person who sought to ignite, we must walk through the layered rhythms of the event as it unfolded and then as it was reconstructed. The first rhythm is the physical: heat, smoke, sounds that resemble a distant thunderclap, the sudden shock of flames licking along a corridor, the way doors become barriers and passageways at once. The second rhythm is social: a crowd coalescing into constellations of concern, then breaking into factions of confidence and doubt as the story’s face changes from hero to suspect. The tension between these rhythms is not merely narrative artistry; it is the stuff of real danger and real justice. When a bystander appears to marshal a crowd toward exit, the bystander’s posture, tone, and timing shape how others respond. They imitate, they accelerate, they breathe in unison with fear, and then they react to what they see and what they think they see. It is precisely in that moment of social imitation that a bystander can flip from noble to malevolent or from savior to saboteur, depending on what the next cue reveals. And in Shaoxing, the cue that finally arrived was the cold, procedural truth of an investigation that showed intention had nothing to do with the relief of others, and everything to do with a motive so small, so ordinary, that it felt almost like a dare to the universe to notice how grotesquely misdirected desire can become.

The rumor of intent travels faster than the flame itself, and it travels through the chest as much as through the air. In the days after the incident, there were conversations among residents about the ethics of action: when is help truly help, and when does a gesture of help become a rehearsal for harm? The public square where people gathered to watch the fire, the security cameras that framed the event from multiple angles, the firefighters whose disciplined choreography turned chaos into order—all of these elements participated in a larger drama about what it means to intervene, to intervene rightly, and to be believed when you claim intention. The figure of the bystander who seems to act with courage, who shouts to pull others out of danger, is a powerful symbol. It invites emulation, secures a sense of communal efficacy, and offers a tangible narrative arc: danger, action, rescue, relief. In the Shaoxing case, the arc would not complete with relief. It would pivot on the discovery that the act of intervention and the act of arson were synchronized by a single mind, a mind that chose motive over mercy and found in a trivial grievance enough justification to tilt a public blaze toward a personal narrative. The triviality of motive is crucial here, for it reveals a human propensity to turn a dramatic canvas into a stage on which one’s personal anxieties seek audience and explanation. A petty grievance, a desire for attention, a momentary intoxication with power over danger—these are the motives that, when given a spark and a crowd, transform a bystander into an arsonist who is also a storyteller, who uses the blaze as a stage for an unscripted reveal.

In the hours when flames make their way through plaster and timber, the bystander’s public posture can be misread as a compass. The first responders see a person directing others away from danger, the crowd sees a familiar face that confers credibility, and the media, chasing a simple plot, tends to reward clarity over ambiguity by labeling the actions in the most legible terms possible: heroism or villainy. The complexity, however, is not easily distilled into a single headline. The Shaoxing case, once the investigation saw through the smoke, revealed a different set of questions: What did the bystander intend beyond the immediate impulse to save? What did he crave from the aftermath? Was there a pattern of behavior that linked this act to others, or was it a singular, almost theatrical, moment in which risk, motive, and audience converged with catastrophic irony? The public, left with more questions than certainties, struggled to reconcile the image of the rescuer with the admission that the rescuer had authored the very situation in which rescue would occur. This dissonance unsettled the faith that communities often place in quick moral judgments. If the person who appears to rescue is also the person who starts the fire, what does the term rescue even signify in such a context? The questions extend beyond the event and into the cultural grammar by which cultures understand safety, courage, and accountability.

There is a literary charge to such a real event, and it is not accidental that the most persistent frame is borrowed from fiction: an ironic mirror in which the instrument of salvation becomes the instrument of ignition, and the fire’s glow is both a beacon and a trap. The case of the Shaoxing arsonist-bystander finds a strange kinship with the logic of certain novels where a spark carries a double meaning. In Lord of the Flies, for example, a fire is a double-edged instrument: it brings rescue in the sense of drawing passing ships or survival’s attention, but it also embodies the boys’ descent into fear-driven organization and the drift toward savagery. That fictional parallel is not a blueprint for real life, but it offers a language to discuss the moral ambiguity that unfolds when the social dynamics of fear, heroism, and visibility become unmoored from clear intent. The bystander who becomes arsonist embodies that ambiguity in a startling, human way: the very act that rearranges a rescue also reframes the act of helping into something that can cause harm, not just because of the flames themselves but because of what the flames reveal about intent, accountability, and the social appetite for narrative closure.

To understand what happened, we need to attend to the physiology of fear and the psychology of attention. When a fire breaks out, the human brain performs a rapid triage: are you in danger? Is danger imminent? What can be done right now to maximize safety? In the midst of that triage, a bystander’s behavior becomes a kind of social signal. If the signal is confident and clear, people will follow; if it is confident but misdirected, people may follow toward harm. The bystander in Shaoxing offered a form of directional leadership that listeners could misinterpret as trustworthy. This is the paradox of risk communication in real time. The same moment in which clear instructions save lives can be co-opted by a self-serving motive that uses the same channels of authority—commanding presence, a sense of duty, a visible display of bravery—to camouflage the true motive. The result is not merely a misreading of events but a misalignment between perception and reality that can delay critical actions. In the moments before the truth was established, witnesses and responders were left to navigate a fog of assumptions as dense as the smoke that curled along the building’s edges.

From the vantage point of a fire-resilience frame, the Shaoxing incident invites reflection on how a city can structure its public spaces to minimize the risk of such irony. If bystander actions are heavily scrutinized after the fact, a city may become overly cautious, potentially discouraging timely action. The opposite danger is to celebrate a heroic posture without scrutiny, risking a culture in which dramatic acts are rewarded regardless of motive. The balance lies in cultivating discernment among the public: the ability to act decisively and calmly when needed, while acknowledging that appearances can deceive and that motives must be scrutinized with fairness. Institutions play a crucial role in this balance. Clear reporting channels, transparent investigations, and robust safety culture help convert a high-stakes incident into a learning opportunity rather than a sensational microdrama. The exchange between immediate, compassionate response and slower, methodical verification is not a contradiction but a necessary choreography. It respects both the urgency of rescue and the integrity of accountability. In the Shaoxing case, that choreography mattered for the living and for the broader community longing for reassurance that courage and truth can coexist on the same stage.

This is where professional fire and rescue training intersects with civic virtue. When the public witnesses danger and acts with intent to help, it is not merely moral energy that is on display; it is the potential for misjudgment to escalate into catastrophe if unanchored by proper knowledge and restraint. In training parlors and real-life drills alike, the emphasis is not only on suppressing flames but on maintaining situational awareness, avoiding improvisation that could endanger others, and recognizing when help should come in the form of clear, measured guidance rather than hands-on interference in ways that could spread the fire or trap people inside. The stories that come out of such incidents are not simply cautionary tales; they are case studies in how communities learn to convert individual courage into collective safety. They remind us that rescue is a social achievement, one that depends on a reliable chain of perception, decision, and action—one that, when tested by a cruel irony, must prove its resilience through honesty, proper procedure, and the humility to acknowledge when a hero’s actions have contributed to the hazard.

In the weeks that followed, the Shaoxing event became a case study for local authorities and safety educators alike. Why did the bystander’s intent appear so benevolent, so aligned with immediate public good, at the moment of crisis? And why did the truth reveal a contrary motive that undercut the moral power of the action? The investigation, while technical in its inquiries, also probes into the social psychology of accountability. It asks whether communities can hold someone to account without denying the human capacity for good, whether resilience can endure the dissonance of a rescue compromised by intent, and how the narrative of rescue can ever be disentangled from the person who precipitated the danger. These questions matter because they shape how people respond to danger in the future. If the public learns that acts of apparent bravery can be subverted by calculated self-interest, the instinct to respond may turn more cautious, more analytical, less impulsive. The risk is not that people will stop helping; the risk is that the help offered will be less certain, less immediate, less confident in its moral framing. The challenge is to cultivate a culture of action that remains anchored in ethical scrutiny, where the impulse to aid is followed by a commitment to truth, and where the line between heroism and hazard is navigated with transparency rather than sensationalism.

As readers reflect on this paradox, it is worth turning to the practical takeaway for those who might one day stand beside a burning structure. The narrative urge is to leap into action, to become a figure of authority the moment danger becomes visible. But the most responsible response is to assume a more structured posture: alert others, call emergency services, and, if safe, assist in orderly evacuation rather than attempting to subdue flame directly with improvised methods that may feed the fire or restrict escape routes. Schools of fire safety training emphasize that the safest action often involves preserving life, not necessarily containing fire in the first instant, and that early, precise communication can buy critical seconds for trained teams to arrive with the right equipment and strategies. The irony—this is critical—lies in how those trained strategies can seem less dramatic than a bystander’s dramatic intervention, yet they are far more effective at preserving life and reducing damage. The public is encouraged to cultivate a readiness to act, but that readiness must be harmonized with restraint, discernment, and discipline. It is not a call to apathy but a call to informed courage, the courage that knows when to step forward and when to step back, when to lead and when to listen, when to trust the trained responders who hold in their hands the knowledge and tools that lay the groundwork for a true rescue.

The narrative arc of Shaoxing’s bystander-turned-arsonist does not end with a simple moral. It invites a broader meditation on how communities interpret danger, how they assign credit, and how they remember the moments that define them. It challenges the reader to consider the ethics of visibility: when does being seen help, and when does being seen unmask a hidden motive that harms those who look to you for guidance? In a culture hungry for clear villains and straightforward heroes, the complexity of this event refuses to simplify without damage. It underlines the need for a public discourse that honors complexity and protects the vulnerable by insisting on accountability. It is a reminder that rescue, at its core, is a shared enterprise. It requires not only the bravery of individuals who act in the moment but the trust of a community that values truth enough to question the instinct to frame every crisis in terms of a singular, telegraphed moral.

The case also leaves a practical imprint on how public spaces are organized and safeguarded. If we accept that the appearance of predictability in a crisis can be as dangerous as the crisis itself, then we must design environments that reduce ambiguity and prevent the kind of misinterpretation that may accompany bystander intervention. This means better crowd management, clearer signage, more accessible evacuation routes, and more robust communication systems that can defuse panic while directing people to safety. It also means a culture in which witnesses understand the limits of their own authority, where they can act with confidence to guide others toward safety while recognizing that consequences can extend beyond the immediate moment. In corridors of power and urban planning alike, the narrative of the Shaoxing fire underscores a simple truth: the resilience of a city is measured not only by how quickly flames are extinguished but by how well its people, institutions, and stories align to ensure that the next act of courage is grounded in truth, accountability, and the shared aim of protecting life.

For readers who want to bring these reflections into a more practical frame, consider the value of ongoing education about safety culture and emergency response. The knowledge embedded in formal training—fire prevention, hazard assessment, safe evacuation procedures, and the disciplined use of personal protective equipment—constitutes a durable foundation that public stories cannot be allowed to erode. It is the quiet, persistent work of professionals and informed civilians that turns a heartrending irony into a future where the impulse to help does not become a catalyst for harm, where the flame that draws rescue does not also draw blame. This is the larger narrative the Shaoxing incident invites us to keep in mind: rescue exists in the balance between action and restraint, between impulse and method, between the story we tell about courage and the truth we verify with careful, patient inquiry. The bystander who started the fire did not merely create a scenario of danger; he created a test case for how a community processes the paradox of rescue. The more we learn to face that paradox with honesty, the more resilient our public life becomes, the more capable we are of turning moments of maximum risk into opportunities for maximum safety. And in that transformation lies the true meaning of a fire that, ironically, brings not only relief but a deeper, enduring obligation to remember, to question, and to act with wiser care in the future.

A final thought lingers in the air like a trace of smoke—how we name the acts of courage in the wake of a blaze, and how we honor those who risk everything to help others. The Shaoxing chapter suggests that courage is not a single act but a pattern of choices: how we balance speed and prudence, how we listen to the signs that a situation might be more complex than it appears, how we insist on truth even when it unsettles our appetite for a clean hero-villain narrative. It asks for a civic humility that welcomes learning from every incident, even when the lesson comes from a moment that challenges our most cherished beliefs about righteousness and intention. In doing so, it offers a more expansive vision of rescue—one that acknowledges the ironies that haunt real life and that reaffirms our shared responsibility to build safer, wiser communities where courage is measured not merely by the audacity to act but by the fidelity to truth, the loyalty to those at risk, and the commitment to prevent harm even as we strive to save.

As you move away from this chapter, carry forward not a simple parable but a set of presences: the presence of danger, the presence of aid, the presence of truth under pressure, and the enduring presence of a community compelled to reflect before it reinforces the stories it tells itself about bravery. If a bystander can spark a rescue with a single gesture, another bystander can also misread a scene and ignite a flame of conflict. The difference lies in the habits we cultivate: rigorous training, deliberate restraint, and a culture that prizes transparency over sensationalism. The Shaoxing incident is less a cautionary tale about bad actors and more a reminder of the fragile architecture of rescue in the modern urban landscape—the architecture that must be designed to support both courage and accountability, to protect life while preserving the integrity of the truth. In that balance lies the chapter’s quiet but indispensable moral: rescue and responsibility are two sides of the same coin, and the ignition of one should never be mistaken for the ignition of the other.

For those who wish to deepen their understanding of fire safety within a broader professional framework, the practical resources available through dedicated training networks can offer guided pathways to safer, more reliable responses in future crises. To connect with instructors and materials that center on essential safety competencies, readers may explore the topic of fire safety essentials certification training, a point of reference that anchors the ideal of preparedness in everyday life and work. This is not an advertisement for a single program but a gateway to a mindset that privileges informed action over impulse, planning over improvisation, and accountability over spectacle. The goal is not merely to survive the next incident but to shape a culture in which courage is inseparable from prudence, and where the lessons learned from stories like Shaoxing’s become daily practice in protecting life and dignity.

External resource: https://www.zjnews.com.cn/news/20260122/1478933.html

When Flame Becomes a Rescue Signal: The Irony and Implications of a Bystander who Starts a Fire That Calls for Help

In the quiet hours of a winter day, when crowds gather in the glow of neon signage and the hum of a city park, an odd sequence unfolded that would linger in memory like a half-remembered fable. A bystander, someone who might have been dismissed as merely part of the backdrop, stepped into the center of a crisis with a peculiar mixture of courage and secrecy. The scene began with a flame, a spark that could have been dismissed as reckless mischief or a fit of panic. Instead, it spiraled into a dramatic irony: a fire started with the intention to reveal danger, to force a response, to compel others to notice pain, and yet the fire rapidly became the mechanism by which rescue was summoned. The case from Shaoxing City’s Yuecheng District, centered on the 1051 Creative Park, offers a stark illustration of how human motives intertwine with public safety in unpredictable ways. The bystander who appeared to be a citizen in distress, a hero in the moment, was later revealed through police investigation to be the arsonist himself. The motive, as it emerged, was not grand or even clearly vindicated by a sense of justice. It was, in the end, trivial and almost incomprehensible in its banality, a reminder that human psychology does not always align with moral clarity or practical outcomes. Yet the irony remains: the very act intended to destabilize the world can provoke a response that stabilizes it, at least temporarily, and in doing so exposes a chain of behavioral dynamics that are themselves worth studying in depth.

The broader implication of this incident, and of similar cases, lies in the paradox at the heart of certain destructive acts. When a fire is started not out of malice toward people but as a desperate signal to be found, to be saved, the fire becomes both a weapon and a beacon. It is a destructive gesture that invites intervention, and in that invitation lies an invitation to examine what the container of that gesture truly seeks. The bystander-turned-arsonist did not light the flame to obliterate; the flame was meant to pierce the cacophony of the everyday and to compel someone, anyone, to step forward with sense and care. And yet, the same flame that functions as a social irritant—an alarm that pulls responders to the scene—also serves as a mirror that reflects the internal state of the person who lit it. The experimental, almost theatrical quality of this act makes it a matter of interest not merely for criminology or public safety, but for psychology, sociology, and the ethics of intervention.

Examining this case requires looking beyond the sensational elements—the urban setting, the rapid mobilization of firefighters, the swift arrival of law enforcement, the media scrutiny—and into the interiors of motive. There is a well-documented pattern in which individuals experiencing emotional turmoil, depression, or acute anxiety engage in self-destructive or risky behavior as if to exceed their own thresholds for distress. The act of setting a fire becomes a signal flare, a way to communicate that something is intolerable and that the person would welcome a form of rescue that interrupts the ongoing internal torment. The public fire then becomes a stage upon which a rescue may be enacted. The rescuers, in turn, might not just extinguish flames and search for injuries; they also perform the critical social function of acknowledging a life that might otherwise be ignored. In this sense, rescue is not merely a physical act but a recognition, a social attestation that someone mattered enough to intervene, diagnose, and fix. The bystander’s desire to be discovered—or to be found—appears in various forms across arson-related cases, and it is frequently linked to mental health challenges that intensify during crises. The NFPA reports that a substantial fraction of non-accidental fires arise not from deliberate malice but from conditions tied to emotional distress, cognitive overwhelm, or a desperate bid to cut through isolation. In such contexts, the line between a rational act of seeking help and a self-destructive impulse becomes dangerously blurred, which makes prevention and response all the more critical.

To understand the Shaoxing incident is to parse a series of ripples that radiate outward into the community. The bystander who played the role of a firefighter in the making—shouting for help, assisting others to evacuate, and physically engaging with flames—appeared to embody both the vulnerability and the courage that public safety campaigns hope to cultivate. The police investigation later revealed that this persona was a disguise of another order: the person who lit the fire was not a villain in the sense of wanting to harm people but someone wrestling with a private crisis so intense that it sought an external stage. The scene at the 1051 Creative Park, a venue known for its creative energy and its crowd of visitors, created a theater of risk where the flame did not discriminate between property and person. Yet the rescuers, drawn by the smoke and the sirens, found themselves offering help not simply to strangers but to a fellow human being who, at the heart of the episode, longed for relief, acknowledgment, and a chance to be seen as someone who mattered. The ironic twist is that the more the bystander sought visibility through danger, the more the community—and the state’s emergency apparatus—became visible to each other. This visibility is a form of social rescue, a harnessing of fear and uncertainty to create a protective frame around the vulnerable.

In the aftermath, the community faced questions that extended far beyond the arsonist’s motives. What does it mean to intervene when a person’s cry for help is muffled by despair, or when the cry emerges as a spark that endangers others? How should responders balance the imperative to save lives with the duties of investigation and accountability? These inquiries do not admit tidy answers, but they do map a landscape where care, suspicion, empathy, and procedure must coexist. The bystander in this narrative becomes a paradoxical emblem of both help and harm, a figure who embodies the ethical ambiguity that often accompanies interventions in times of crisis. Public safety officials, mental health professionals, and community leaders can draw from this case a broader lesson: distress signals can arrive in many shapes, including the dangerous shape of a flame, and the most effective response hinges on a rapid, compassionate, and well-coordinated approach that treats distress as both a medical concern and a public safety concern.

What does it mean to read a case like this with an eye toward prevention rather than punishment? Prevention, in this sense, rests on early, accessible channels of help and on a public culture that treats emotional suffering with seriousness rather than stigma. If a person in acute distress finds a way to reach out, even through a perilous channel, the response should be swift and nonjudgmental. This does not absolve responsibility for dangerous acts; rather, it reframes responsibility as a shared obligation to reduce the probability that people feel compelled to choose a path of destruction as a way to survive an oppressive moment. In practice, that means robust crisis intervention resources, accessible mental health services, and public messaging that normalizes seeking help. It also means that bystanders, friends, family, and coworkers learn to recognize the cues of escalating distress and respond with concrete, immediate support rather than leaving a person to navigate crisis alone. The Shaoxing case underscores the importance of bridging the gap between private vulnerability and public safety by creating pathways that intercept destructive impulses before they crystallize into acts that threaten others.

The psychology underpinning arson as a cry for help reveals a landscape where self-destructive urges and a latent need for intervention can coalesce in a dramatic, newsworthy moment. The NFPA has highlighted that many non-accidental fires are not simply misdeeds but expressions of psychological conflict. When shaped by situational stressors—social isolation, unemployment, family strain, or a collapse of perceived control—these impulses can magnify. In such cases, people may enact a dramatic scene because it seems to them to offer a form of external validation that their pain is real and observable. The rescue operation then becomes a social response that confirms, in a highly visible way, that someone noticed the pain, took it seriously, and intervened. The irony is not merely that rescue follows flame; it is that the act of rescue confirms the value of the person at its center, even if the initial act was aimed at drawing that very attention through danger. This paradox invites a careful, nuanced analysis rather than a quick moral judgment. It suggests that the most effective protection against similar tragedies lies not only in punitive measures but in a compassionate framework that recognizes distress signals in their complexity and responds with a spectrum of supports.

Within this framework, the bystander who started the fire that willfully drew rescue can be read as a case study in how social environments shape responses to distress. The public setting matters: a creative park, a community hub, a place where people expect inspiration rather than peril, becomes the backdrop against which a private crisis is dramatized. The crowd’s reaction—alarm, hurried evacuation, the orderly arrival of firefighting teams, and the eventual stabilization of danger—creates a counter-narrative to the private one of the arsonist’s inner turmoil. The persons who handle the crisis—emergency responders, law enforcement, medical teams, and volunteers who assist with shelter and information—perform not only technical duties but also social acts of resonance. They acknowledge that danger is real and that courage comes in countless forms, including that of those who feel unseen but want desperately to be seen. The emotional labor of rescuers, viewers, and the bystander-turned-arsonist therefore becomes a shared narrative about recognition, care, and the fragile boundary between suffering and safety.

From a policy perspective, the Shaoxing incident reinforces the need for multi-layered strategies that address not just the mechanics of fire response but the human factors that precede and accompany it. Educational campaigns that illuminate how distress can manifest and how to seek help early, community-based support networks that identify at-risk individuals before crises erupt, and accessible mental health resources that meet people where they are are all essential. It is not enough to tell people to call for help; the system must be prepared to respond with minimal barriers, rapid triage, and sustained follow-up. Public awareness campaigns must destigmatize mental health challenges while maintaining clear distinctions between signs of distress and the moral or legal boundaries that govern risky or criminal behavior. In this regard, the bystander-turned-arsonist case becomes a cautionary tale about the limits of intuition in crisis situations. It invites a recalibration of how communities imagine resilience: resilience is not merely the ability to endure a crisis, but the capacity to mobilize a supportive social ecosystem that prevents crises from becoming catastrophes.

The aim of this analysis is not to romanticize the fragile line between intervention and endangerment, but to illuminate how the psychology of motive and the social ecology of response intersect in real events. The bystander who lights a flame to force a response is also a person with a need to be understood at a moment when understanding feels safest and most protective. Recognizing this duality helps responders craft interventions that are both humane and effective. It encourages researchers, educators, and policymakers to ask deeper questions about how to design spaces and services that interrupt cycles of distress before they culminate in dangerous acts. It challenges communities to cultivate a culture in which help is not only available but is expected, in which asking for help is a sign of strength, and in which the flame of danger never becomes the only signal that a person matters.

In closing, the Shaoxing case serves as a reminder that human actions, even when seen through the lens of danger, are rarely singular in motive. A fire can be a cry, a confession, a misguided attempt at salvation, and a test of a community’s capacity to respond with clarity and care. The bystander who appeared to be a hero in the moment may have been driven by private pain that we can barely imagine. Yet the public rescue that followed underscores a hopeful truth: when a community listens, adapts, and acts without prejudice, the flame that threatened to erase a moment of life can instead illuminate a path toward greater safety, stronger support networks, and a renewed commitment to the idea that every person deserves dignity and help in times of crisis. The episode thus becomes not only a story about irony but also a blueprint for how societies can respond with empathy and efficacy when danger arrives wearing the familiar face of a neighbor, a passerby, or a person in distress seeking to be seen.

Further exploration of these dynamics can be found in the body of research that links arson to psychological factors and the broader question of why some people choose such extreme signals in moments of vulnerability. The interplay of self-destruction and intervention, the symbol of fire as both threat and beacon, and the social mechanisms that mobilize rescue all converge in a narrative that is as instructive as it is unsettling. For those seeking more granular insights into the psychology behind arson, see the external resource Understanding the Psychology Behind Arson. As communities continue to grapple with cases that reveal the unexpected motives behind destructive acts, it will be essential to maintain a calm, evidence-based approach that foregrounds prevention, early support, and the humane treatment of distress as a public health priority. Meanwhile, the practical steps for citizens and responders include recognizing warning signs, fostering open channels of help, ensuring rapid access to crisis services, and maintaining the readiness of emergency response systems to act decisively while safeguarding the rights and dignity of all involved. In this way, the flame that once threatened to erase a moment can be redirected toward saving lives and reinforcing the social fabric that binds a community together.

External resource: Understanding the Psychology Behind Arson (https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research/Data-research-and-publications/Fire-Statistics/Arson-and-Other-Intentional-Fires)

Internal link reference: For practical steps that communities can take to improve crisis response and safety culture in everyday settings, see fire safety essentials certification training. This resource offers guidance on how ordinary citizens can prepare to act responsibly in emergencies, support others in distress, and coordinate with professional responders during complex events. fire safety essentials certification training.

From Irony to Impetus: The Fire That Triggered Rescue and What It Reveals About Public Response and Emergency Services

In Shaoxing’s Yuecheng District, a fire tested assumptions about safety, trust, and rescue. A bystander who seemed to shield others became the architect of the disaster, and authorities suggested the motive was trivial. The incident reveals that rescue is a social practice, not a solitary act, and that public response depends on credible and coordinated action. The bystander’s double role—alarm, then concealment—complicates the narrative of heroism and asks how communities calibrate trust in emergencies.

The case also invites a broader comparison with wartime rescue networks. In World War II’s Pacific Theater, air-sea rescue expanded survival and morale, while Japan’s more limited system shaped risk calculus and decision making. The contrast shows how the availability of rescue can influence risk-taking and cooperation with authorities. Rescuers and bystanders alike become part of a social contract: visible capability, transparent reporting, and continuous improvement strengthen public confidence in safety infrastructure.

Viewed today, the Shaoxing incident underscores that rescue is a public enterprise requiring training, clear communication, and humility from those who marshal help. It is not enough to aspire to heroic acts; communities must invest in reliable networks, accountability, and ethical standards so that rescue—whether urban, disaster, or wartime—remains credible and effective for all.

Final thoughts

The troubling incident in Shaoxing serves as a powerful reminder of the complexities and unpredictable nature of human behavior during crises. A bystander turned arsonist not only triggered chaos but inadvertently spotlighted the critical roles emergency responders play in restoring safety and order. This case challenges the community to reconcile its perception of heroism and dire miscalculations. As both a cautionary tale and a moment of reflection, it calls for more comprehensive awareness and understanding of the motivations behind such actions and their consequences. Ultimately, recognizing the multifaceted nature of human intentions can foster better community relations and more effective emergency responses in the future.