In scenarios of fire emergencies, the instinct to save what matters most brings forth a question: What possessions would one prioritize? Nin emerges as a symbol, possibly embodying the heroic efforts of individuals faced with such dilemmas. This exploration delves into the essence of possessions worth saving, beginning with an investigation of what Nin might rescue from flames. Each chapter further investigates policies, historical precedents, the cultural importance of salvaged items, and the role of individuals in responding to fire crises. By connecting these elements, we aim to cultivate an understanding of what possessions are deemed invaluable during fire emergencies, guiding individuals, auto dealers, fleet buyers, and businesses towards more informed decisions.

What Nin Might Rescue from the Fire: A Fluid Investigation into Memory, Meaning, and the Hidden Value of Possessions

In imagining Nin confronted with a blaze, we enter a space where the boundary between fear and values loosens. The scene is not a news report but a quiet experiment in what a person, real or fictional, would choose to save when every breath feels borrowed and time slows to the crackle of flames. Nin’s identity—whether a myth, a public figure, or an everyperson—matters less for the outcome than for what the choice reveals about attachment. If Nin could grab only one possession, what would it be? The answer, as the research threads suggest, would hinge less on price than on memory, story, and the sense of who Nin is in the world. In this chapter, the question becomes a doorway into how people understand themselves through the things they keep. It is a thought experiment, yes, but one that opens a larger conversation about what a life values when its structure is at risk of collapse. The question also invites us to examine how culture teaches us to narrate a rescue. What counts as a treasure to protect is never merely about material worth; it is about continuity, identity, and the intimate pages of a life story pressed into a container, a frame, or a fabric that time cannot erase.

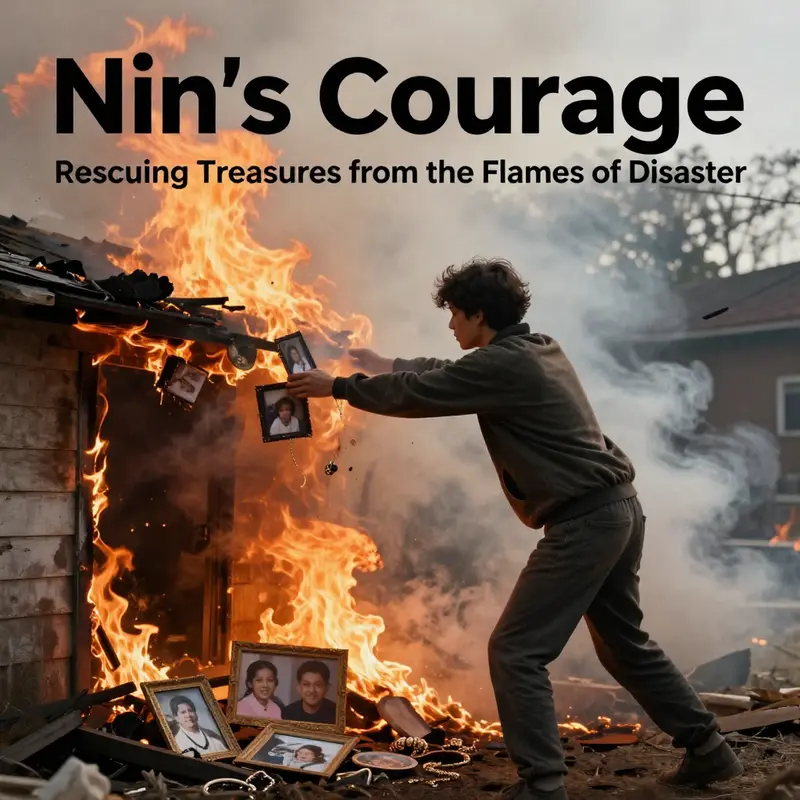

When we speak of possessions in the wake of danger, sentimental value emerges as a guiding principle. The items most often chosen in crisis are not the most expensive or technically sophisticated. They are the ones that carry the weight of memory. Family photographs, for instance, are compact repositories of generations of warmth, laughter, and shared laughter. They anchor the self to a lineage that can seem fragile in moments of upheaval. Heirlooms—items passed down through generations—carry a narrative continuity that promises resilience beyond the immediate threat. They are not just artifacts; they are the fingerprints of ancestry, the visible threads that connect a person to those who came before. Personal mementos—letters, handmade crafts, a favorite blanket—function as portable shelters for emotion. They remind us how fragile the present is and how durable memory can be when pressed against loss. In Nin’s hypothetical choice, it is the emotionally saturated object, not the financially valuable one, that would likely be saved first. This is not a romanticization of sentimentality but a recognition of how memory structures personhood. The act of selecting a single item, in a moment of high stress, becomes a declaration about who Nin is and what Nin believes matters most when the ground shifts beneath the feet.

From a psychological vantage, the phenomenon has a consistent logic. Researchers in consumer psychology have shown that people derive greater satisfaction from preserving items tied to their life experiences. The emotional value supersedes monetary value because memory provides identity in a form that objects alone cannot. An item becomes a vessel for a life’s narrative, a portable archive that can be revisited to restore a sense of self after the crisis passes. In Nin’s hypothetical scenario, the selected object would likely serve as a touchstone that makes the person’s history legible again after it is shaken. The choice is less about what is left behind and more about what remains understood. The emotional resonance of a chosen possession can function as a mnemonic anchor, a way to reconstruct meaning in the aftermath when almost everything else feels uncertain. This insight helps us appreciate why the narratives around who Nin is—and what Nin saves—carry weight not merely as anecdote but as a window into the human psyche under pressure.

The broader cultural dimension deepens the story. Across communities, objects are not mere things; they are carriers of shared memory and social bonds. A photograph may hold a family’s collective mood at a particular moment; an heirloom may articulate a lineage’s values and taste. In many cultures, objects serve as storytellers, validating the past while guiding future behavior. When a fire threatens what we own, the act of saving something precious becomes an act of storytelling in the moment. It is a decision that says: this is what we carry forward. The person who saves the old family portrait is choosing memory over novelty; the saver of an old diary is choosing narrative continuity over the uncertain present. The arc of the rescue then becomes a microcosm of life itself: we cling to the chapters that explain who we are and why the story continues when fear tests the fidelity of our memory.

Crucially, such choices illuminate the social dimensions of possession. A single item, saved or spared, reveals the frictions between personal sentiment and social obligation. A keepsake tied to a spouse or parent can reflect intimate love; a memento connected to a child may embody hope for the future. The moment of rescue is a negotiation between self and others, between the private history we guard and the shared stories we pass on. In Nin’s case, the imagined choice might also reveal ethical considerations—how to balance personal memory against the safety of others, how to decide between preserving a keepsake and ensuring everyone’s safety in a chaotic scene. The psychology of attachment meets the ethics of care in that confluence where memory, value, and responsibility intersect.

The tales of real people who have saved cherished items during fires, as reported in various outlets, lend texture to this theoretical frame. They remind us that the most valued objects often carry a weight that transcends market value. A photograph of a grandmother on a mantelpiece, a letter that speaks of a long-ago promise, a hand-knit blanket that wrapped a newborn—these items become anchors when the room seems to tilt. The BBC has highlighted stories of such rescue acts, underscoring how personal attachments guide choices in crisis. These narratives do not diminish the danger or diminish the courage involved; rather, they illuminate the psychological map of what humans regard as irreplaceable in a moment when everything else is at stake. The link below points to one of the public accounts that illustrate these intimate decisions in real life, offering a corroborating texture to the theoretical frame of Nin’s imagined rescue.

As we circle back to Nin, the imagined choice remains a lens rather than a verdict. If Nin is a stand-in for any person facing crisis, the act of choosing a single possession becomes a ritual of meaning-making. It shows how memory incubates identity and how identity sustains resilience. The item Nin saves, while small in the physical sense, stands as a monument to a life’s narrative. It is a symbol of prioritized story over silence, a claim that some memories deserve protection even when all else is compromised. And in that moment, the act of saving is also a way of shaping the future—of saying that some parts of the past will survive into whatever comes next. In this sense, Nin’s hypothetical rescue is less about the object saved and more about the person who saves it—the quiet assertion that a life is navigated by the compass of memory, values, and the stubborn hope that meaning endures beyond smoke and ash.

For readers who want a sense of how practical safety and memory-related value intersect in everyday life, a closer look at safety education can be illuminating. The discipline of safety training emphasizes not only protocols and procedures but also the mindset that allows people to act under pressure. Learning to prioritize, to assess risks, and to communicate clearly during a crisis all contribute to preserving what we most care about. The internal perspective offered by such training complements our imagined scenario with a concrete framework for action. If Nin’s choice were to be informed by preparation, the act of rescue would be less improvisational and more guided by a practiced habit of safeguarding memory and meaning. This alignment between emotional intention and concrete readiness is a reminder that our possessions matter not only because of what they cost but because of what they preserve when circumstance disrobes us of certainty. The practical lessons—planning, drills, and the discipline of clear-headed action—are the backbone that allows a life to recover after loss, and they echo the same impulse that drives Nin to choose a single piece of history over a larger, more expedient sale of time.

To connect these reflections with ongoing conversations, see the broader discussions on fire-safety literacy and personal preparedness. Practical engagement with safety concepts makes it possible to translate the sentimental logic of Nin’s rescue into everyday prudence. For readers who want to explore this connection further, consider engaging with resources that foreground both memory and preparedness. And for those who crave a concrete path to enhance personal resilience, the following internal link offers a concise bridge to the kinds of safety education that illuminate why people save what they save. Fire Safety Essentials Certification Training.

As this chapter moves toward its close, the focus remains on the human heart behind the gaze of the flames. Nin’s hypothetical decision is not a puzzle with a single answer; it is a mirror held up to memory, to love, and to the stubborn human instinct to preserve the essence of a life in the face of threat. The story invites us to consider how we would act, what we would save, and why those choices matter. It asks us to name the objects that make a life coherent, to acknowledge the deep moral and emotional work of prioritizing memory, and to recognize the quiet moral economy by which people allocate their precious resources in moments of danger. And if the tale of Nin teaches us anything, it is that the fire tests not just our possessions but the narrative we carry forward into the world beyond the flames. In that sense, the single object chosen to survive an eruption of heat becomes a kind of beacon—reminding us that what endures is not simply a thing but a memory carefully guarded by a person who understands that some possessions are, in the most intimate sense, part of who we become.

External reference: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52694170

From Ash to Asset: Reframing Fire Safety Protocols in Hypothetical Rescues of Nin’s Possession

The prompt about Nin’s possession sits on the boundary between a concrete incident and a hypothetical exercise. The existing materials do not record any individual named Nin performing a rescue of possessions from a fire. Yet that absence becomes a useful lens for examining how fire safety protocols, especially within the United Nations Security Management System (UNSMS), are designed to protect both people and the material anchors of mission work: the bags, documents, equipment, and mementos that carry operational value and institutional memory. If Nin’s possession were a real object in a fire, the questions would quickly shift from “what happened” to “how did the safety architecture perform under pressure, and what did it preserve.” In other words, the case becomes a microcosm for the broader triad of prevention, preparedness, and response that fire safety relies upon in complex environments. The chapter that follows treats this triad not as a narrow checklist but as a living, evolving practice that mediates risk, preserves function, and sustains mission continuity even when the fire devours the obvious and reveals what endures behind it.

To move from the hypothetical to the practical, consider first the domain of prevention. The UNSMS framework anticipates that the smallest, most vulnerable elements—valuables, critical records, and personal effects—are part of a ledger of assets to be safeguarded. Prevention begins long before flames touch a surface: it begins with risk assessment that recognizes the specific properties of objects that might be at stake. In some operations, possessions range from physical tools and sensitive documents to digital devices that house mission-critical data. The prevention mindset translates into layered protections: robust storage solutions that balance accessibility with security, redundancy in document handling, and routine checks that ensure fire detection and suppression systems are functional and appropriately calibrated for the types of risks that are most likely to arise in a given setting. Even when a possession is not itself a life hazard, its loss can cascade into operational paralysis. The chapter keeps that awareness at its core and sees prevention as a form of asset stewardship rather than mere physical containment.

Yet prevention cannot stand alone. Preparedness—training, drills, and clear protocols—forms the bridge between protection and action. In practice, preparedness means that when alarms sound, responders know who is responsible for what, where to go, and how to prioritize efforts without compromising the safety of personnel. It also means that guardians of possessions understand the decision criteria for salvage: which items are essential for immediate operations, which are irreplaceable records, and which can be temporarily set aside to facilitate human safety. The preparation phase thus becomes an occasion to codify tacit knowledge—the subtle cues a trained team uses to gauge smoke progression, heat flux, and potential routes of egress—into explicit procedures that can be practiced, tested, and refined. The aim is not to eliminate risk entirely but to minimize it to an acceptable level while preserving the integrity of critical items that support mission-readiness.

The timing of detection and warning is the fulcrum upon which prevention and response pivot. Fire detection devices, alarms, and communications networks are not ornamental add-ons; they are the cognitive sensors of a rapidly changing crisis. In UNSMS settings, where personnel operate in volatile, multi-stakeholder environments, timely information sharing and coordinated alerts shape how quickly teams can enact protective measures for both people and possessions. A well-designed detection system provides early visibility into hazards, allowing decision-makers to activate a salvage mentality where appropriate. The chain of communication must be swift and trusted, reaching field teams, base staff, and, when necessary, external partners whose support preserves mission continuity. The aim is to convert environmental signals into actionable intelligence, turning a potential catastrophe into a series of manageable steps rather than a single overwhelming event. In this sense, the hypothetical Nin situation underscores the broader truth: the value of a possession is inseparable from the speed and clarity of warning that accompanies its peril.

Response, in a functional sense, translates plans into action under pressure. The rescue of a possession, were it to occur, would likely unfold within the same disciplined structure that governs all UNSMS operations: a unified incident command, a demonstrateable commitment to life safety first, and a systematic approach to asset protection that respects both the physical and informational dimensions of what is at risk. The rescue would require real-time risk assessment, a balance between aggressive extraction and the avoidance of unnecessary exposure, and a flexible script that accommodates evolving fire behavior. The movement of people must remain the primary objective, yet experienced responders also recognize that some possessions hold strategic value. A salvage decision is rarely a binary choice; it is a continuum where the probability of successful retrieval, the likelihood of collateral damage, and the potential impact on ongoing operations are weighed against the imperative to preserve life. Even when a possession cannot be recovered, the response phase should aim to recover data, maintain traceability, and ensure continuity for the mission’s next steps. The narrative surrounding Nin’s hypothetical rescue becomes a way to illuminate how responders manage competing priorities in a high-stakes environment. It invites readers to see that the preservation of items is not a separate, isolated task but an integrated dimension of the overall safety architecture.

The chapter’s results point to a crucial truth: data about a specific person or incident, such as Nin and a particular possession, is less important than the integrity of the safety system that would govern any such scenario. The UNSMS context emphasizes consistent standards, recurring training, and interoperable procedures that can be applied to diverse situations. When a fire threatens a valuable object, the protocols aim to ensure that any salvage action is grounded in principled decision-making, clear lines of authority, and a commitment to documenting outcomes for continuous improvement. That means salvage plans should be paired with robust record-keeping: inventories, photographs, timestamps, and chain-of-custody for recovered items and evidence. The hypothetical Nin case thus becomes a catalyst for discussing how an organization translates a narrative impulse—the rescue of a possession—into disciplined practice that protects people, preserves critical assets, and enables a swift return to operational normalcy once the flames are gone.

The discussion also encounters the inevitable tension between forest-fire safety tips and the realities of a built environment. While much of the research highlights forest fire suppression safety, the underlying principles translate across contexts: situational awareness, timely evacuation, and the use of protective equipment appropriate to the risk. In forest contexts, the focus is on understanding fire behavior, fuel loads, and escape routes; in urban or field-based UNSMS settings, the emphasis shifts to building layouts, fuel sources, electrical systems, and access for responders. Yet both arenas share a core conviction: a well-prepared team, with clearly defined roles and trusted communication pathways, can significantly reduce losses and increase the odds that critical possessions and mission-essential materials survive. The synthesis of these perspectives underscores the universal value of preparedness and the adaptability of safety protocols to different terrains and scales of risk. The hypothetical Nin scenario thus serves as a bridge between theory and practice, encouraging readers to appreciate how a generic rescue mindset can be operationalized without relying on any single narrative of a person or event.

To bring this back to the everyday work of safeguarding assets, the chapter also invites practitioners to consider how training translates into tangible capabilities. Professional development in fire safety—such as the comprehensive preparation that underpins the ability to respond effectively in crisis—becomes a foundation for any rescue operation. The internal link to training resources emphasizes how ongoing education supports the broad aim of asset protection. For those tasked with implementing these standards, practical training in fire safety essentials certification training helps ensure teams are not only compliant but capable. This emphasis on training is not a distraction from the main narrative; it is the mechanism by which dry requirements become living competencies that teams can deploy under pressure. The chapter remains mindful of the fact that explicit data about Nin does not exist in the current material. Yet the emphasis on training, planning, and practiced response remains directly relevant for any organization seeking to safeguard possessions when fire threatens.

The overarching lesson, then, is less about naming a particular possession or a singular rescue and more about the architecture of safety itself. A possession is only as secure as the framework that protects it. The UNSMS-inspired approach treats assets as part of a broader system that prioritizes people, integrity, and continuity. In that sense, Nin’s hypothetical rescue becomes a case study in risk-aware behavior, not a rumor to be traced or a story to be validated. It is a reminder that the most compelling narrative of a fire is not about a singular moment of salvage but about the chain of decisions that preserves what matters: the health and safety of personnel, the reliability of operations, and the capacity to recover and resume work with as little disruption as possible.

External resource and further reflection can deepen the reader’s understanding of how these principles function in practice. For those seeking a grounded framework, professional guidance on occupational fire safety and prevention offers essential context. For instance, general safety standards and workplace guidelines provide concrete steps that organizations can adapt to their missions and environments. By weaving together prevention, preparedness, and response, the chapter outlines a cohesive approach to safeguarding possessions and mission-critical assets, even when the narrative of Nin remains unverified in the source materials. The aim is not to foreground a disputed identity or a disputed possession but to demonstrate how strong safety protocols create resilience when every item has a story worth preserving.

External resource: https://www.osha.gov

From Salvage to Safety: Tracing the Historical Arc of Personal Possessions in Fire Rescue—and What It Means for Nin

Fire rescues have long carried the echo of a question that sounds practical, almost intimate: what possessions are worth pulling from a burning building when every breath of air and every heartbeat feels like a deadline? The historical record answers with a layered, evolving judgment. For generations, the chief aim of firefighting was not merely to stop flames, but to salvage value—economic, sentimental, and documentary. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, as cities grew denser and homes wore their flammable materials as badges of modern progress, personal belongings carried considerable weight in both the ledger and the heart. Fire insurance had become a common wall between risk and ruin, and a house fire was as much a disruption of a family’s narrative as it was a blaze of heat and smoke. In that world, firefighters often ventured into smoke and embers not only to save lives if present, but to recover heirlooms, manuscripts, and keepsakes that families presumed would be lost forever. The calculus of risk was different; the potential payoff—a cherished letter, a grandmother’s jewelry, a family photo album—could justify the peril of entering a structure that might collapse around them. It was an era where the boundaries between rescue and retrieval blurred, and the line between public service and private memory was sometimes negotiated with the tools and temper of the time.

This orientation toward salvaging valuables did not arise in isolation. It reflected a broader social economy in which homes were built with materials that burned readily, and where the content inside carried outsized economic and emotional value. Firefighters were expected to protect both the structure and its contents, a mission that extended beyond extinguishing flames to preserving the story those items carried. In many communities, speed and thoroughness in retrieval were as celebrated as the courage to confront heat. The public understanding of what a rescue could mean was anchored in tangible goods—the family silver, a bankbook, a ship’s manifest, a stack of irreplaceable photographs—precious remnants of daily life that defined a family’s continuity in the wake of disaster. The practice of salvaging belongings, then, operated within a logic of preservation that prioritized property alongside life, and it was normalized by the visible, material nature of the losses that fires inflicted.

Yet, a shift in thinking began to unfold as science advanced and the rhetoric of safety began to supersede salvage as a normative objective. The evolution of fire behavior knowledge—how flames spread, how heat and smoke travel, how structures fail under stress—reframed the calculus of risk for responders. As fire science matured, so did the professional doctrine surrounding what should and should not be risked in a blaze. The emergent consensus placed human life squarely at the center of emergency response. International frameworks and standardized protocols codified this priority: evacuate and protect lives first, minimize risk to responders, and limit non-life-saving operations in the heat of the moment. In this light, entering a burning building solely to retrieve belongings became increasingly discouraged, and in many jurisdictions it was prohibited unless a controlled, low-risk scenario allowed for such salvage without endangering lives.

Legal and ethical considerations sharpened the shift. Liability concerns loomed large for emergency services, and the calculus of benefit versus risk grew more complex. Communities demanded accountability when a rescue attempt went awry, and insurers, insurers’ clients, and the public at large demanded clearer, safer standards for how responders operate in perilous spaces. Building codes evolved in tandem, emphasizing safer construction and better fire resistance. The result was a dual strategy: reduce the likelihood of valuable belongings being lost in the first place through prevention, and, when fires do occur, pursue life safety with greater discipline, using protective equipment, rapid evacuation, and risk-managed operations. The emphasis on prevention—through education, planning, and better materials—became as central as any immediate rescue operation. In this context, the possession, while still cherished, assumed a secondary position to the imperative of protecting lives and limiting danger to those who respond to the emergency.

At the level of policy and standards, the global trend toward prioritizing life safety is evident in national and international norms. Notably, there are references in contemporary guidelines that articulate general principles for emergency response that foreground human life and responder safety. The case of China’s GB/T 46793.1-2025, a guideline about emergency response plan compilation, signals a broader move toward structured preparedness that gives prominence to life safety over salvage. Such frameworks provide a backbone for how communities organize response, allocate resources, and communicate risk. They also reflect a growing emphasis on proactive planning, which includes drills, public education, and hazard mitigation that reduce the necessity of any post-fire retrieval drama. In sum, modern doctrine codifies a culture of caution, where the retrieval of personal possessions is not a default objective but a carefully considered option, conditioned on the absence of danger to lives and during operations designed to keep responders out of harm’s way.

The shift from salvage to safety also reframes a familiar, almost intimate impulse—the desire to recover a keepsake that anchors a family’s memory. The sentimental value of objects like photographs, letters, or heirlooms remains powerful, but the professional environment now coaches people to preserve memory through nondestructive means: documentation, digital preservation, and careful storages that resist fire and smoke. Public institutions and private households alike have learned to protect what matters most by design—fire-resistant safes, archival storage, and the use of fire-rated containers for important documents. These measures complement the legal and ethical emphasis on life safety, because they acknowledge the persistent human need to hold on to memory while also recognizing that memory forged in a dangerous moment can never replace the living safety of those who are still in danger.

Cultural expectations around resilience and remembrance further illuminate why this historical arc matters to modern readers. In many societies, families tell stories of resilience through objects that survived a blaze or were recovered by a rescuer’s steadfast hands. Those narratives, though often dramatized, reflect a communal attachment to the material traces of identity. They also illustrate a broader tension: the urge to salvage and the obligation to prevent harm. As fires became less predictable and urban life more complex, communities learned to express care for memory not through risky retrieval but through institutions that protect records, artifacts, and family histories in safer ways. The result is a civilization that values the legacies housed inside a home while recognizing that protecting people is the primary, defining objective of any emergency response.

Within this historical frame, the Nin question enters as a modern inquiry about responsibility, heroism, and the nature of memory. If a reader encounters a claim that Nin rescued a cherished possession from a fire, this chapter helps place such a claim in a broader context. The absence of Nin in the early rescue record should not be read as denial of heroic acts, but as an illustration of how public memory sometimes extrapolates from dramatic moments into personal myth. The careful historian, and the careful reader, checks the provenance of dramatic rescues against the measured evolution of practice. The risk calculus, the shift in priorities, and the preventive strategies all argue for a cautious interpretation: the story of Nin’s possession rescue, if it exists, would be a recent or local variation rather than a reflection of long-standing practice. In the context of this history, the question of what possession was saved becomes simultaneously a question of how safety norms have changed and how communities teach and remember their own emergencies.

For those who teach or train future responders, the practical implications of this arc are clear. The field emphasizes preparation over improvisation, prevention over post-fact retrieval, and the ethical weight of entering danger only when it serves life or when it is part of a controlled operation. Skills and knowledge are built around rapid risk assessment, the use of protective equipment, and the discipline to withdraw when the risk outweighs any potential gain. To connect learning with practice, consider the resources that translate historical lessons into contemporary competence. For practitioners and students seeking practical grounding in how safety culture translates to field skill, see fire safety essentials certification training.

The historical arc thus informs a contemporary sensitivity to what is worth saving and what must be left to time and prevention. It also makes explicit why an authoritative account would not routinely attribute a possession rescue to a single individual in a way that contradicts the prevailing emphasis on life safety. The human impulse to recover memory is real, and the memory of a home’s contents can be powerful. Yet the professional memory of firefighting is now defined by the clarity that lives matter first, that risk to responders must be minimized, and that the most lasting value comes from preventing fires and preserving documents and memories through safe, forward-looking practices rather than through risky, on-the-spot retrieval. In this sense, the Nin narrative is best understood as a modern inquiry that asks for evidence, consistency, and alignment with current safety standards.%0AExternal reference: https://www.un.org/peacekeeping/operations/management-system

What Survives the Blaze: The Cultural Power of Salvaged Possessions in Fire’s Wake

When a community is struck by fire, the visible scars are stark: charred structures, empty lots, and the flattened outline of a neighborhood’s former life. Yet within the ash, a quieter economy of memory begins to unfold. Salvaged possessions become more than reminders of what was lost; they function as tangible threads that bind people to each other, to generations, and to a sense of futures still possible. In this sense, the cultural significance of what survives is less about the material value and more about the meanings embedded in everyday objects: a worn photo album that preserves a family’s faces, a letter tucked behind a frame that carries a voice from the past, a book whose pages have yellowed with time yet whose ideas still spark a conversation across decades. Objects salvageable from a fire do not simply exist as remnants; they become stubborn carriers of identity, history, and communal resilience. They invite a community to tell its story again, perhaps differently, but with the same core knots of memory, obligation, and hope.

The thread that runs through salvaged possessions is not only personal memory but collective turnaround. When personal lives are disrupted by disaster, the act of salvaging is a counter-movement to despair. It is an assertion that the human storyline does not end with smoke and debris. The recovered items—whether a stack of photographs recovered from a ripped album, a handwritten letter saved from a scorched envelope, or a cherished keepsake retrieved from a damaged trunk—often become the starting point for reconstruction. They allow families to teach younger members about who they are, where they come from, and what they intend to preserve for the future. In parliamentary terms, they become touchstones of identity; in more intimate language, they are keepsakes that anchor the self to a past that has not disappeared, even as the present demands new arrangements and improvisations.

In thinking about salvage, it is important to acknowledge how the social fabric adds layers to the significance of the items themselves. A home is not just walls and floors; it is a nexus where routines, rituals, and relationships take shape. When a fire interrupts those patterns, salvaged objects may carry the weight of social history as much as personal history. A grandmother’s quilt, once dusty and faded, can become a living artifact—worthy of repair, reuse, and storytelling. A set of old family recipes, rescued from a scorched notebook, can rekindle shared meals and cultural practices that bind neighbors who have begun to rebuild together. The emotional conversations tied to these objects—about where they were held, who touched them, and what they signified in daily life—reconfigure memory into a shared project of recovery. The chapter of a life that was burning can still be written, not merely read, through what people manage to retrieve.

There is a notable public case that illuminates how salvage can extend beyond the private sphere and become a form of communal care. In the wake of a devastating wildfire, a local pharmacy—though not a grand institution—stood as a central pivot for the community’s wellbeing. The store’s founder-managed effort to preserve critical data despite the destruction demonstrates how salvaged information can sustain a community’s health and continuity. This act did more than protect business records; it kept the lifeline of medical care intact for displaced residents who depended on affordable or deferred-payment medicines. Data salvage transformed the salvaged bits into a symbol of continuity, trust, and care. It suggested that resilience is not merely about rebuilding walls but about preserving relationships and services that keep a community intact as people search for a new normal after chaos.

The cultural significance of salvaged data, when viewed alongside tangible belongings, expands the conversation about what it means to recover from disaster. The notion that your memory is inseparable from the items you own is amplified when those items survive the inferno. Yet when the physical object is lost, the salvaged data—records, correspondence, digital footprints—may carry the same weight. They enable the continuation of essential services, support the transmission of knowledge, and sustain social ties that might otherwise fray during displacement. In this light, salvage becomes a form of preserving a community’s moral economy—the informal set of obligations, care, sharing, and responsibility that exist when formal systems are stressed or strained.

This reflection comes with a caution about how we frame the idea of possession. The question—what possession does Nin rescue from the fire?—is not what most emergency narratives focus on, because the historical record often lacks a named rescuer tied to a single item. Instead, the more resonant inquiry concerns the kinds of possessions that communities heal through salvaging and the functions those objects perform in the process of recovery. It is not only about what is saved, but who is involved, how meaning is attached, and what collective memory the act generates for the days that follow. In many stories, salvage becomes a communal ritual rather than a solo act. People share, swap, and restore items, and in doing so, they rebuild not just homes but also the social ties that make a neighborhood feel safe again. The salvaged objects thus become emblems of endurance, whether they are kept in a family album, displayed in a new home, or archived in a community center that remains a place of gathering and mutual aid.

The broader narrative then points to a core truth: salvaged possessions are not isolated relics; they are interfaces between memory and action. A photograph recovered from a fire is a link to the past, but it also prompts questions about how to care for those memories going forward. Will future generations preserve the image in a new frame, write a story around it, or create a digital archive that makes the moment accessible to a wider circle? A letter recovered from a scorched envelope may become a doorway into family history, inviting readers to reflect on the ways voice, handwriting, and even the cadence of a sentence carry emotional resonance. Heirlooms are not merely decorative but performative—reminding communities to honor their ancestors while negotiating the practicalities of rebuilding homes, schools, and streets.

If there is a practical throughline in this discussion, it concerns preparedness and the stewardship of memory. The cultural power of salvaged possessions rests, in part, on how a community organizes, preserves, and interprets what it saves. This includes the spaces in which salvaged items are kept, the stories that accompany them, and the actions that follow. It also involves the preparation that families and institutions undertake before disaster strikes—planning for safe storage of irreplaceable mementos, digital backups of important data, and robust records that can be recovered even when physical copies are damaged or lost. The more intentional the approach to safeguarding memory and health information, the more likely a community will be able to maintain continuity in the face of upheaval. In this context, a simple belief—that the past can be held even when the present is unsettled—becomes a strategic asset for resilience.

In considering this, we acknowledge that not every salvage story is dramatic or widely known. Some recoveries play out in ordinary rooms: a grandmother’s recipe book rescued from a cabinet, a schoolyearbook salvaged from a locker, a child’s stuffed animal found in the rubble and washed clean by repeated hands. Each item, small or large, becomes part of a tapestry of recovery. The intangible heritage—the rituals of caregiving, the acts of sharing resources, the repeated acts of repair—carries forward even when the visible signs of loss fade. The cultural significance of salvage thus rests not only in the items themselves but in the social practices that surround them. Documentation, storytelling, and community remembrance ensure that the salvaged past is not merely archived but activated in the present.

As we weave these reflections into the broader arc of the article, it is essential to note that the narrative of salvage often intersects with policy, philanthropy, and community organizing. When communities rally to protect and recover their memories, they also create infrastructures that can withstand future shocks. This is where the suggestion of practical steps—such as strengthening data backups, supporting access to affordable healthcare during displacement, and investing in community archives—becomes more than prescriptive advice. It becomes a path toward a more resilient cultural practice. In this sense, salvaged possessions become, paradoxically, a blueprint for rebuilding: not just rebuilt houses, but rebuilt ways of living together.

For readers seeking a concrete illustration of these dynamics, the discussion of the Camp Fire-era recovery offers a compelling case study. In that context, the salvaged data and the community’s response demonstrated how care persists when infrastructure is compromised. To explore this further, see the NPR account that examines the lasting legacy of the event and the role salvage played in sustaining care for displaced residents. This external perspective helps situate the intimate, personal stories of memory within a wider social and historical frame. https://www.npr.org/2020/09/15/911637493/the-legacy-of-paradise-drug-after-the-camp-fire

In closing, the question of what Nin rescued from the fire may remain unresolved in the historical record. Yet the broader answer—what salvaged possessions signify for memory, identity, and community resilience—offers a powerful lens for understanding recovery. Salvage is less a single act than a continuing practice: an ongoing negotiation between loss and continuity, between ash and memory, between the private and the public good. It is through this dynamic that individuals and communities learn not only to survive but to carry forward the stories that define them. And in that carrying, the ordinary items saved from the blaze become extraordinary instruments of meaning, binding past, present, and future into a shared, enduring narrative.

Internal link: fire-safety-essentials-certification-training

Nin and the Fire: Myth, Memory, and the Boundaries of Possession

This chapter explores the question of what Nin might rescue from a fire as a way to examine memory, myth, and the limits of historical record. It asks who survives the blaze, which objects matter to readers, and how symbolic value can outlast material loss. A name becomes a hinge around cultural longing, and the text questions whether we should measure a rescue by a tangible object or by the persistence of meaning after the heat has passed. The absence of a documented incident is not merely a blank; it marks a boundary within which we read, interpret, and distinguish between what happened and what readers want to believe happened. The exploration treats the question not as a report of a real event but as a lens on how audiences use famous names to test memory and attribution. It invites consideration of how much weight a single figure can bear when the historical scaffolding around them is incomplete, and how imagination fills gaps with symbolism and sometimes sentimentality. From the archival angle, the evidence indicates that Anais Nin, who lived from 1903 to 1977, did not participate in any known fire response. Her life is understood through her diaries, her published works, and the conversations she sparked with peers and readers. Her legacy lies in inner fires of consciousness, the courage to articulate intimate experience, and the practice of turning crisis into narrative insight. This is not an absence to dismiss; it is a boundary that helps prevent a misreading of Nin as a public crisis responder. The diaries and novels reveal a spectrum of emotional heat rather than acts of rescue. The genuine disappearance here is the retrieval of a tangible object, and what endures is a way of seeing the world that outlives material loss. The real rescue, then, is the preservation of thought, voice, and method that can illuminate readers across generations. On a broader note, the meaning of possession in fire safety shifts from objects to life, memory, and learning. Real emergencies depend on priorities such as life safety and rapid action, not on the fame attached to a person. The narrative suggests that the strongest form of preservation is not a recovered object but a saved way of thinking that continues to teach and to challenge. If readers want practical knowledge about emergency response, credible frameworks emphasize preparedness, teamwork, and the prioritization of human life. Resources and training materials provide credible guidance that complements literary inquiry by grounding curiosity in real world safety practice. For those who wish to connect these reflections to safety culture, the point is to separate symbol from event and to recognize that credible memory rests on evidence, sources, and transparent methodology. The lasting possessions are ideas, words, and the capacity to think critically under pressure. To support readers who pursue these questions, credible references on fire safety history and standards can offer an external anchor for discussion, alongside archival histories that document the interplay of myth and fact. The upshot is not a tale of heroic rescue but a reminder that culture preserves what can be thought and communicated, long after flames are extinguished.

Final thoughts

Nin serves as a powerful representation of those faced with the dilemma of saving what is invaluable in emergencies. The exploration of what possessions are worth rescuing—from irreplaceable memories to essential artifacts—affirms the emotional and cultural significance attached to personal belongings. Through analyzing fire safety protocols, historical contexts, and cultural implications, we grasp a deeper awareness of the human experience during crises. As we aspire to understand what Nin represents, we are reminded of the courage required to confront flames that threaten our lives and treasures.