The evolution of aircraft for fire and rescue operations is a testament to human ingenuity and the quest for safety. Beginning in the early 20th century with the electrifying invention of the airplane by the Wright Brothers, this progression paved the way for unique applications in emergency services. As aviation technology advanced, its role expanded into critical life-saving operations, transforming how we respond to crises. Each subsequent chapter will delve into these milestones, highlighting the pivotal moments in aircraft use for firefighting and rescue missions, the revolutionary developments in this field, and the state-of-the-art innovations that define modern emergency aviation—a journey from rudimentary flight to advanced aerial firefighting techniques.

Wings of Necessity: From the Wright Brothers’ First Flight to the Modern Rescue Sky

The moment when the first powered, controllable, sustained flight shifted from a curiosity to a possibility is etched not just in aviation history but in the collective imagination of every field that relies on speed, reach, and precision. On December 17, 1903, the Wright Brothers demonstrated that a machine could leave the ground, command itself in three dimensions, and return with a degree of reliability that invited a future of possibility. They did not set out to solve firefighting or search and rescue, yet their breakthrough reframed what is possible when human effort and mechanical design align with the laws of aerodynamics and control. Their Flyer I proved that air travel was not a dream but a domain that could be domesticated, scaled, and refined. From that seed grew a lineage of machines—airplanes and later helicopters—that would become essential tools in emergencies, enabling helpers to reach the injured, the stranded, and the vulnerable at speeds and angles of access impossible from the ground alone.

What followed was a gradual translation of a history of ascent into a history of deployment. Early flight experiments gave rise to new ideas about mobility in time and space, ideas that found their most potent expression in the military and medical domains during the 20th century. Aircraft began to shift from novelty to necessity as nations faced the brutal realities of war, but also as civilian communities learned to anticipate the needs of people in peril. In the crucible of conflict, planes and, later, rotorcraft demonstrated that air power could be a direct line to safety, not merely a symbol of speed. The concept of evacuating the wounded, of delivering doctors to the scene, or of ferrying essential medical supplies into difficult terrain moved from theoretical possibility to routine practice years after the Wrights’ triumph, gradually shaping a discipline that would be called air medical rescue or flight medicine decades later.

The bridge between the Wright Brothers and the modern fire and rescue mission is not a single inventor or a singular device but a continuum. In World War I, the battlefield had a brutal tempo that demanded rapid medical evacuation. Planes did not yet have the refined handling and loads of later generations, but they demonstrated the undeniable value of moving a patient from danger to care with speed and continuity. The patient could begin to receive attention far earlier than field transport allowed, and the idea of a medical module in flight—essentially a moving treatment environment—took root in the minds of physicians and engineers who watched these early aircraft perform on the edge of feasibility. Although the term flight medicine would not crystallize for several decades, the seeds were sown here: air access could shorten the time to life-saving intervention, which is often the decisive margin in trauma and critical illness.

The path from fragile first flights to robust air rescue systems would take shape over many years, through reforms in training, technology, and organization. The interwar period and the years that followed brought improvements in engine reliability, control systems, and payloads. Engineers and clinicians began to treat air transport as a specialized operation with its own safety considerations and medical criteria. It was not enough to build a machine capable of flying; a team had to be assembled with medical expertise, aviation know-how, and a clear understanding of mission priorities. This evolution occurred in many countries and communities, each adapting to local needs, terrain, and resources. The result was a mosaic in which airplanes and helicopters, though sharing a common ancestry, filled complementary roles in rescue and emergency response.

In this broader arc, a notable shift occurred in the 1970s, when a new mode of aerial care emerged in Germany that would become a template for flight medicine worldwide. Helicopters were increasingly used to bring doctors directly to patients rather than waiting for patients to be transported to a hospital. This was a decisive reimagining of how emergency expertise could be delivered—moving care closer to the point of need and reconfiguring the patient’s journey from injury to treatment. The approach emphasized speed, on-site assessment, and the ability to administer critical interventions within a moving, dynamic environment. It also highlighted the centrality of coordination—between aircraft, medical teams, ground responders, and hospital facilities—and underscored the need for robust training pipelines that could prepare clinicians and pilots to work together in unpredictable conditions.

The technological trajectory that began with the Wright Flyer therefore did not stop at flight itself. It expanded into the science of ascent, descent, navigation, and payload management, all tailored to the demands of rescue work. Across decades, the tools evolved from fragile airplanes to purpose-built aircraft that could carry medical monitors, suction devices, and even specialized extraction gear. In forested or mountainous regions, helicopters could reach locations that would have stymied ground crews, whereas fixed-wing aircraft offered long-range reconnaissance, rapid transport between distant sites, and the capacity to deliver larger teams or equipment when time mattered most. The combined power of aviation and medicine—this synergy of aeronautical engineering and clinical judgment—began to define modern air rescue as a discipline with its own ethics, its own standards, and its own culture of teamwork and precision.

As flight technology advanced, so did the operational concepts that govern how these machines are used in emergencies. Aerial reconnaissance allows responders to size up a scene from above, discern the terrain, map access routes, and identify hazards that would complicate ground operations. Water and fire retardant drops—carefully calculated for efficiency and environmental impact—become practical when crews can reach the correct altitude and approach vector without compromising those on the ground. The ability to deliver small, precise drops, deploy rapid-deploy teams, or hoist patients from otherwise inaccessible locations represents a qualitative shift in rescue efficiency. And because wildfires, floods, and other disasters often propagate in complex, layered ways, aerial assets must work in concert with ground teams, command centers, and hospitals. The largest gains come not from a single piece of equipment but from an integrated system in which aircraft, weather information, geographic data, and medical protocols align to reduce risk and maximize patient outcomes.

The scholarly and institutional memory of aviation confirms that the origin of such systems lies in that earliest, audacious flight experiments, not in a single breakthrough and not in a single decade. The modern rescue aircraft owe their lineage to the fundamental principles demonstrated by the Wright Brothers: control, stability, and purposeful propulsion. The practical lessons those principles generated—how to manage lift in varying air conditions, how to coordinate throttle and aileron, how to translate the sensation of flight into reliable, repeatable performance—became the bedrock of all later rescue missions. Without a flight capable of delivering people and gear quickly to a site, the ethos of saving lives through distance, altitude, and speed would have never become standard operating practice. The Wrights did not design a fire-truck that could fly; they designed a flying machine that made every subsequent emergency airborne capability imaginable.

From the mid-20th century onward, the story of flight in rescue work is as much about people and procedures as it is about propulsion. It is about training, maintenance, and the social organization of rapid response. It is about the culture that forms when a team knows that seconds matter and that the sky is a strategic space for saving lives. This culture grew out of places of learning and experimentation, from university labs to airfields, where engineers, physicians, and emergency responders tested new configurations, refined medical kits for in-flight use, and established protocols for coordinating air missions with on-ground operations. Each successful mission built trust in the concept that aerial access is not a luxury but a necessity in managing catastrophes, whether those catastrophes take the form of raging wildfires, remote medical emergencies, or large-scale disasters where every minute carries weight.

To understand how deeply this evolution runs, it helps to anchor the story in a broader historical landscape. The Wright Brothers’ achievement sits at a human crossroads: a moment when curiosity met measurable capability, when a country, and then the world, began to imagine flights that could be deployed for purposes beyond sport or exhibition. The subsequent decades turned imagination into a workforce, a set of standard practices, and a body of knowledge about how to fly safely while performing complex tasks. The field matured through a continuous feedback loop: missions informed design, design informed training, training improved mission effectiveness, and improved outcomes fed back into policy and resource allocation. In time, the aerial rescue enterprise would come to depend on not just a skilled pilot or surgeon but a full ecosystem of aviation weather services, load management, flight planning, patient care standards, and post-mmission debriefing. Each element reinforces the others, ensuring that when a helicopter lowers a rescuer to a cliff face or a plane ferries a team across a river, the mission has the best possible chance of success.

The present is in dialogue with that past. Today’s air-and-ground rescue operations carry forward a lineage of problem-solving born in the earliest experiments with flight. The same concerns exist: how to reach the right place at the right moment, how to maintain safety in unpredictable environments, and how to ensure that the care delivered in the air is as rigorous as the care delivered on the ground. The engineering choices may look different—composite materials, advanced avionics, multirotor efficiency, and robust life-support systems—but the core questions echo the Wrights’ early inquiries: how to balance stability and maneuverability, how to maximize payload while preserving safety margins, and how to synchronize human teams with mechanical capabilities so that each mission becomes more than the sum of its parts. In this way, the history of flight medicine and aerial rescue is not a new branch grafted onto aviation; it is a continued extension of the same cultural impulse that gave us the airplane itself—to imagine, to test, to refine, and to apply in service of human welfare.

This perspective also invites us to consider the educational side of aerial rescue. Training is the quiet backbone of every successful mission. It is the discipline that translates theoretical aerodynamics into reliable performance under stress, that teaches crews how to manage a hoist line, how to operate in low-visibility conditions, and how to deliver care while the landscape slides past at tens or hundreds of knots. The emphasis on training is a direct extension of the idea that flying is a team sport. Pilots, paramedics, physicians, loadmasters, and ground specialists must share a mental model of the mission, a common language for communication, and a shared appreciation for risk management. This is where the lineage of aviation and emergency medicine begins to cohere. A modern rescue operation uses sophisticated equipment, but its effectiveness ultimately rests on the people who train together, rehearse together, and bring a calm, purposeful presence to every approach and extraction. For readers curious about the human dimension of aerial rescue training, a look at dedicated training facilities and programs—such as those described in the Firefighter Training Tower Dedication article—offers a window into how culture and competence are built in parallel with technology. Firefighter Training Tower Dedication

If one threads the narrative from the Wright Brothers’ first controlled flight to today’s intertwined systems of aviation and emergency medicine, a clear throughline emerges: the sky is transformed from a barrier into a corridor of action. The aircraft that once symbolized speed now symbolize access—access to patients who would otherwise face delays that threaten recovery, access to remote communities where ground teams cannot reach quickly, and access to safety for crews who must operate under the pressure of fire, flood, or collapse. The technologies supporting this corridor—avionics that stabilize flight in gusty conditions, sensors that map heat and smoke, medical devices engineered for portability and resilience—are the heirs of early experimentation, refined through decades of practice and collaboration. They remind us that innovation in rescue aviation is not a single stroke of genius but a sustained culture of learning, iteration, and partnership across disciplines and borders.

The Wright Brothers’ legacy, then, is not a solitary chapter but a continuous invitation to reimagine what is possible when flight becomes a platform for human care. Firefighting and emergency response do not exist apart from aviation; they have always depended on it, in ways that are both practical and profound. The airplanes and helicopters that now crown hillsides to shed water, or that hover over a train wreck to stabilize a patient, or that quietly shuttle a surgeon to a rural clinic, all carry forward a simple conceit from 1903: when speed, reach, and precise control converge with preparation and care, the difference between danger and safety can hinge on a wingbeat. The story of planes for fire and rescue, therefore, remains one of synthesis—of art and science, of risk and remedy, of history and immediate encounter with need. It is a story that continues to unfold wherever communities depend on air access to safeguard life and limb, and it began with a small, stubborn aeroplane that dared to fly. For readers seeking a broader historical panorama beyond the specifics of the early pioneers, the National Air and Space Museum offers a detailed account of the Wright Brothers’ experiments and the evolution of flight as part of a larger narrative about human ingenuity and exploration: https://airandspace.si.edu.

From Wrights to Lifesaving Skies: The Evolution of Aircraft in Firefighting and Rescue

The question of who made planes fire and rescue invites a long, interwoven narrative rather than a single name. It traces a continuum from the moments when a controllable flight opened the air as a working space, to a modern era in which aircraft are essential nodes in a broad, technologically networked response to wildfires and other emergencies. The foundational act remains the same: a flying machine that can carry people, tools, and payloads to places unreachable by ground. Yet the significance of that act deepens as the purpose of flight shifts from demonstration to decisive intervention. The Wright brothers opened the door to a future where planes and their successors would transcend mere movement and become platforms for saving lives, preserving ecosystems, and connecting scattered communities with rapid, life preserving capability. This lineage helps explain why the current aerial firefighting and rescue enterprise looks so different from the early days, and why it continues to evolve at a pace driven by urgency, technology, and the expanding scale of threats posed by climate change and cascading disasters. In digging into the evolution, we move beyond heroic singular moments and toward a practical, cumulative story of capability building that binds aviation history to emergency response practice.

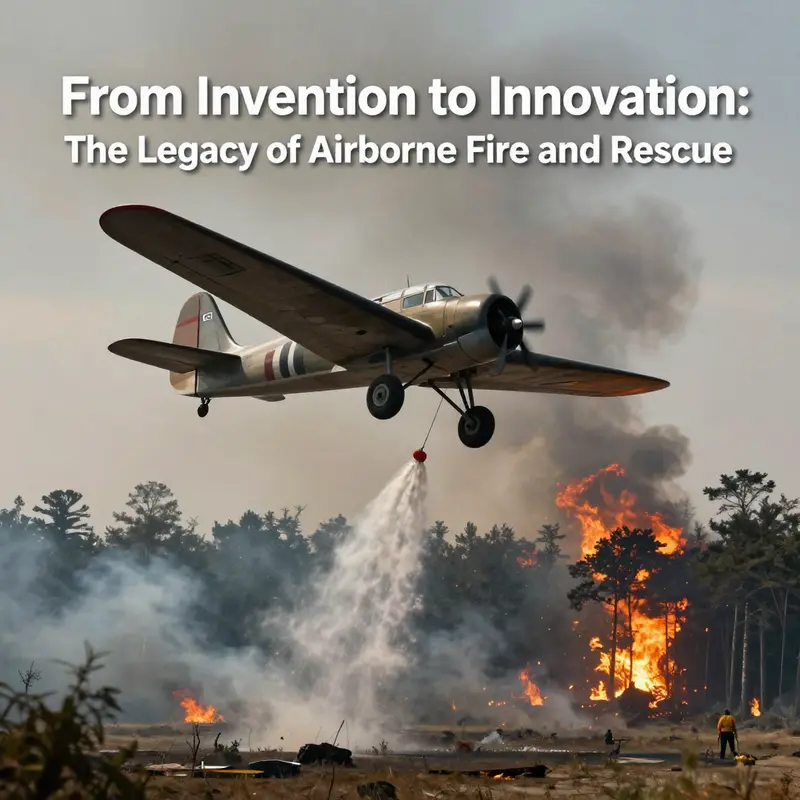

The earliest chapters of aerial wildfire management reveal a shift from observation to intervention. In the first decades of the 20th century, air sampling and reconnaissance flights offered forest managers new eyes in the sky. A fixed wing aircraft tasked with surveillance could map fire lines, monitor terrain, and relay findings back to ground crews. This reconnaissance role, modest in its immediate effect, laid the empirical groundwork for later, more proactive uses of air power in fire control. By the mid-1920s and into the 1930s, nations began to extend that role into direct engagement. Fixed wings were used not merely to watch but to transport water, equipment, and supplies to support ground crews, and to lay the groundwork for the more aggressive strategy of aerial suppression. The evolution here is subtle but crucial: the airspace becomes an operational theater where timing and precision determine whether a fire front grows or abates. The 1940s marked a turning point when air assets started to contribute directly to suppression efforts in forested regions, a sign that aviation was becoming a central, not peripheral, element of wildfire management.

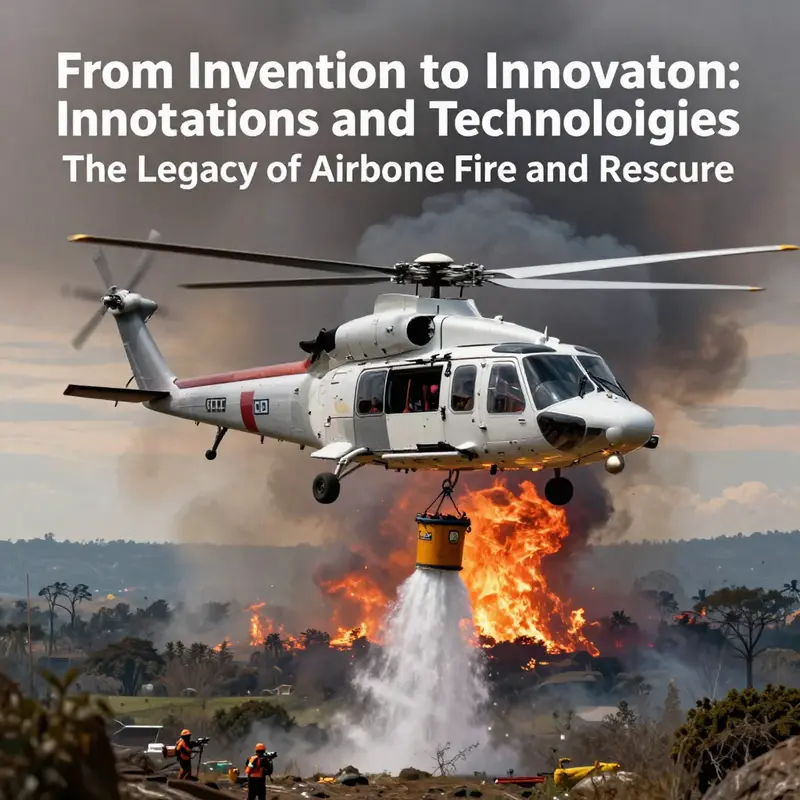

In the ensuing decades, a different class of aircraft redefined rescue at scale. Helicopters emerged as a distinct game changer when they showed up as mobile medical stations and rapid responders, capable of delivering doctors and nurses directly to patients in remote or dangerous locations. This era, which matured in the 1970s in parts of Europe and elsewhere, gave the field a new operational language: flight medicine, air assault, and on scene evacuation. The helicopter became more than a vehicle for transport; it was a versatile platform for triage, stabilization, and rapid extraction. The medical rescue mission in the air could arrive at a scene with clinical teams and equipment, then depart with a patient who needed urgent care, all while ground units prepared for what would come next. This transformation from a passive observation asset to an active, on scene intervention tool marks a philosophical shift in the use of air power for emergencies. The long arc from reconnaissance to airborne care set the conceptual stage for the broader integration of air resources into comprehensive emergency response plans.

Across the globe, regional adaptations of aerial firefighting reflect the uneven geographies and governance frameworks that shape how fire and rescue operations are organized. In Asia, forest defense organizations built a robust air capability through decades of development, gradually aligning aerial assets with ground crews, weather services, and terrain-specific tactics. In Europe and North America, the push toward integrated aerial operations intensified as agencies formalized training, standardized procedures, and cross jurisdictional agreements that allowed shared use of air assets during large incidents. China, for instance, organized early aviation fire protection centers and progressively expanded its capabilities with structured models for station based teams, high altitude operations, and cross provincial coordination. Each increment—whether it is mapping water sources for water drops, establishing landing zones in uneven terrain, or coordinating air-ground communication systems—reinforced the idea that aerial assets must operate as an integral part of a larger response network. The common thread across these developments is not the pursuit of novelty for its own sake, but a deliberate, practice oriented evolution intended to improve the speed, accuracy, and safety of interventions when fire encroaches upon communities and ecosystems.

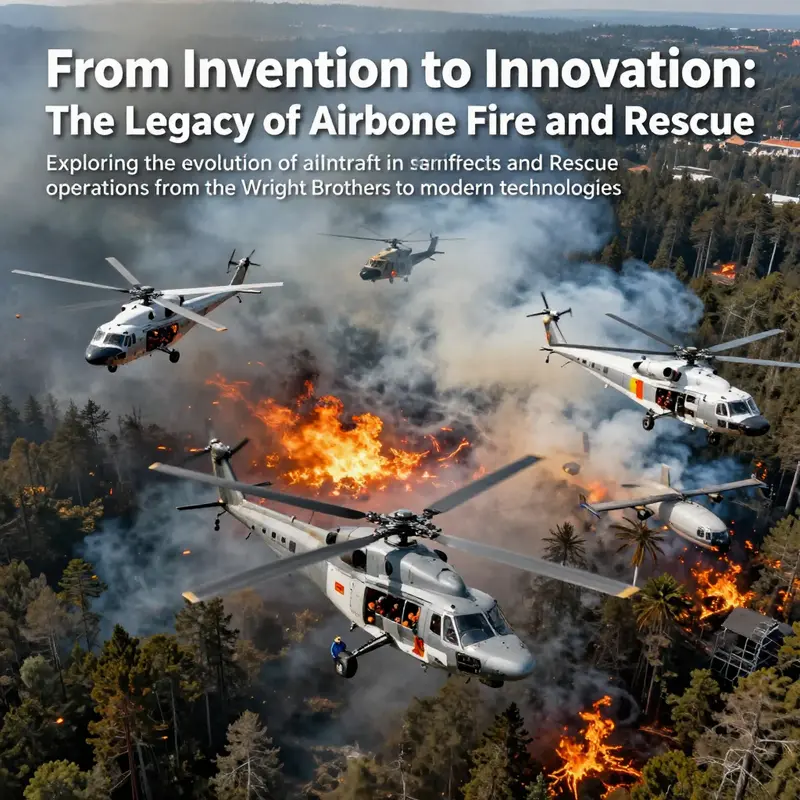

In practice, the modern repertoire of aerial firefighting and rescue has grown into a comprehensive suite of operations designed to protect lives and landscapes. The simplest components—bucket drops and water delivery systems—have matured into highly choreographed sequences that can couple with chemical retardant approaches to slow or redirect a fire’s advance. Aerial personnel drops and the on scene transport of medical staff extend the reach of ground teams to remote locations, enabling on scene care that might otherwise be impossible. Cargo delivery supports sustained operations by delivering gear, tools, or recovery equipment to crews where access is blocked. Medical evacuation remains a core capability, letting patients receive urgent care while ground responders reassess routes and priorities. Public awareness campaigns, often run in parallel with immediate response, help communities prepare, reduce risk, and understand how to respond when fires threaten neighborhoods or rural livelihoods. The vehicles themselves have diversified to match the demands of varied terrains and mission sets, with large, specialized helicopters and fixed wing fire bombers joining a growing class of unmanned aerial systems. The shift toward unmanned platforms signals a new dimension in risk management and decision making, letting operators gain real time information, conduct reconnaissance without risking crew, and extend reach into areas too dangerous for manned flight.

The evolution is not merely about adding new toys to the toolbox; it is about rethinking the tempo and geometry of response. Aerial suppression methods have become increasingly sophisticated when paired with ground and space based surveillance, forming a triad that can be activated and coordinated through integrated command structures. National forest and emergency plans have increasingly emphasized aerial response as a central element, with broader strategies to expand available fleets, optimize allocation of resources, and reduce the time between detection and action. The logic of response has shifted from a strictly reactive posture to a proactive, networked approach in which real time data, predictive modeling, and rapid payload deployment shape the choices made on the ground. In some regions, the goal is to stitch together a seamless aerial emergency response network that can operate across provincial or regional boundaries. As climate change intensifies the frequency and ferocity of wildfires, the air component grows in importance because it often becomes the first multiplier in a multi layered response that includes suppression, evacuation, and post fire recovery.

Several threads weave the current practice together. The first is the recognition that the airspace itself is a dynamic domain requiring constant situational awareness. Modern air-ground-space surveillance systems collect data from multiple sources and translate it into actionable intelligence on fire behavior, wind shifts, and topographic risk. This integrative approach supports rapid decision making about where to drop water or retardant, when to deploy ground crews, and how to stage medical support near hotspots. A second thread concerns the evolution of fleets and payloads. The fleet has grown beyond ad hoc renovations of military aircraft to include purpose built, rugged, and adaptable airframes engineered to carry water, foam, or retardant over large areas. The balance between speed, capacity, and precision has driven innovations in drop mechanisms, delivery accuracy, and flight safety. A third thread concerns the growing role of technology in enhancing accuracy and resilience. Drones and other unmanned systems extend perception into dangerous zones, while intelligent command platforms unify the actions of pilots, operators, and ground teams into a coherent tempo. This convergence yields more precise reconnaissance, better allocation of resources, and improved safety for crews operating in volatile environments.

Beyond the hardware and software shifts, the human dimension remains central. Training, coordination, and leadership structures have evolved to reflect the demands of large, multi agency responses. The integration of aerial units with local fire services, disaster management agencies, and health services requires clear lines of communication, standardized procedures, and shared terminology. Exercises and simulations now routinely incorporate air ground space elements, so that when a real event unfolds, responses can be scaled rapidly without producing confusion or conflict among different agencies. The social organization of air operations—how pilots, firefighters on the ground, medical teams, and air traffic controllers interact—has become an essential element of effectiveness. In a world where fires can move with astonishing speed and unpredictability, the imperative is not simply to arrive first but to arrive with the right capability, at the right place, at the right moment, so that the entire incident action plan can gain momentum and save lives.

Recent decades have also witnessed a shift toward more integrated and resilient networks. In several regions, official planning documents have set out ambitious goals to expand aerial firefighting assets while building robust aerial emergency response networks that can operate across jurisdictions. The trend toward networked capability is paired with a growing emphasis on multi modal coordination, so that air assets link with ground crews, water sources, and medical facilities in a coherent, bottom up as well as top down fashion. In practice this means more systematic mapping of landing zones and water sources, more detailed pre incident planning for specific terrains, and more flexible air bases or forward operating bases that can be established quickly to support operations in challenging landscapes. The result is a more agile, more dependable response system that can adapt to shifting fire behavior, weather, and human needs. The aim is not to render ground crews obsolete but to create a synergistic relationship where aerial action buys ground teams the time they need to secure lines, rescue victims, and protect communities.

The pace of innovation in aerial firefighting and rescue continues to accelerate. In recent years, the push toward a dual air ground space strategy has led to the emergence of advanced collaborative models that blur the line between manned and unmanned aviation. Drone swarms can provide real time reconnaissance, transmit high fidelity data streams, and help build three dimensional models of an evolving fire. Large capacity unmanned helicopters promise the ability to carry and deploy substantial payloads with precision while keeping human operators at a safe distance from the most dangerous fronts. When these technologies are combined with well trained crews and well designed command platforms, they create a kind of networked intelligence that extends the reach of emergency responders and allows them to act decisively in the critical hours after a wildfire is detected. In turn, this capability translates into measurable improvements in response times, suppression effectiveness, and the safety profile of operations for both crews and residents.

As readers consider the arc from the earliest reconnaissance flights to the present day, it is important to keep in mind the underlying purpose of aviation in fire and rescue missions: to translate speed into safety, and to convert aerial presence into a disciplined, strategic advantage on the ground. The evolution described here is not a series of isolated breakthroughs but a continuous adaptation to the demands of real world incidents. Each advancement—whether it is a more capable water drop system, better coordination between air units and ground crews, or a more sophisticated understanding of how to stage and preserve water sources, landing zones, and medical evacuation routes—builds toward a more resilient, responsive emergency response architecture. This architecture is designed to operate under pressure, to negotiate with weather, to navigate hazardous terrain, and to deliver critical payloads with the precision that saves lives and protects ecosystems.

If one looks for a through line, it is the passage from the airplane as a symbol of risk and exploration to the airplane as a trusted partner in the most demanding rescue and firefighting operations. The transformation reflects a broader shift in society’s relationship with risk—from conquering air to harnessing air for collective safety. The legacy of the Wright brothers provides the starting point, but the story is written by countless pilots, engineers, emergency responders, and planners who have translated flight into rescue. Today, the airspace is a critical corridor for evacuation and for delivering suppression agents, medical care, and relief rapidly to people and places in harm’s way. The evolution continues as climate realities push for faster, smarter, and more integrated responses. The frontier is not only about how far and fast planes can fly, but about how well the entire system can work together to protect lives, livelihoods, and landscapes when the skies darken with fire.

For readers seeking practical perspectives on how communities can advance their own aerial response capabilities, the broader conversation is enriched by professional insights and case studies compiled by practitioners across the firefighting and rescue communities. These discussions emphasize readiness, interoperability, and continual learning as the bedrock of effective aerial response. They also highlight how communities can invest in training, upskilling, and scenario planning to ensure that when the first warning sirens sound, the air becomes a partner rather than a barrier. As the chapter threads together the historical arc and the contemporary practice, it becomes clear that the evolution of aircraft in firefighting and rescue is not merely a tale of machines but a narrative about how people harness technology to keep one another safe in moments of extraordinary peril. The story does not end with a single milestone; it continues in every coordinated drop, every dawn patrol, and every on scene decision that turns the air from a threat into a lifesaving instrument. The skies, once a frontier for exploration, have become a shared space where technology, teamwork, and timing converge to protect lives, homes, and habitats from the growing reach of fire.

As a further reference to the broader context of aerial firefighting and its development over time, readers may consult external analyses of how firefighting strategies have evolved in major fire events and across different regions. These sources illuminate how the integration of air assets with ground forces and medical response has shaped outcomes in large incidents and how lessons learned feed back into training, policy, and practice. For an overview of how California and similar landscapes have evolved in firefighting, see a detailed examination in Live Science on the evolution of firefighting approaches and the role of aviation within them. https://www.livescience.com/evolution-of-california-firefighting

Internal reference for practitioners and enthusiasts seeking training related perspectives can be found through the FIRE RESCUE Blog, which gathers insights on preparedness, certification, and field readiness. This resource offers practical notes on how training translates into operational effectiveness when aerial assets are deployed in complex emergencies: FIRE RESCUE Blog.

From Wright Brothers to Water-Scooping Rescuers: The Evolution of Fire and Rescue Aircraft

The question of who made planes fire and rescue is less a single name and more a lineage of invention that begins with the first controllable flight and stretches into today’s multi-mission air fleets. The Wright brothers proved that a powered, controllable machine could rise into the sky and stay there long enough to be guided by human judgment. Their achievement did not signal a dedicated fire or rescue purpose, but it established the fundamental possibility: air travel could be purposeful, precise, and repeatable. In the years that followed, the use of aircraft for emergency purposes began to crystallize in much more pressured contexts. World War I introduced the practical idea that airplanes could evacuate wounded soldiers from front lines, a rudimentary but real forerunner of medical airlift. If the early airframes demonstrated flight, later generations would demonstrate mission—how to deliver aid, rescue, and medical care efficiently from the air to the ground or water. The arc from those early flights to today’s sophisticated systems is marked not by a single name or invention, but by a continuum of engineering, policy, and field experience that progressively redefined speed, precision, and resilience in emergency response.

In the decades that followed, aviation medicine and rescue operations began to cohere around the concept of flight as a critical intervene in life-and-death situations. The postwar period witnessed incremental improvements in aircraft performance, navigation, and crew training, yet the real transformation came when flight could be integrated into a larger network of emergency services. This network would unite air, ground, and medical professionals in a shared mission: to reach victims where ground access was too slow, too dangerous, or physically impossible. The shift from airborne observation to airborne intervention accelerated in moments of crisis—wildfires sweeping across continents, earthquakes tearing through cities, floods rising with little warning. As these events multiplied in scale and complexity, the demand for airborne responders grew louder, and the design of aircraft for fire and rescue matured from ad hoc expedients into deliberate, mission-specific platforms.

Modern fire and rescue aircraft thus occupy a different place in the emergency-services ecosystem: they are not merely tools that drop water from above but integral components of a dynamic, intelligent system that blends long-range reach with surgical delivery. The most visible leap is the advent of heavy-lift aerial firefighting systems. These are large, fixed-wing platforms capable of rapid water pickup from lakes or rivers, followed by precise drops over fires that stretch across vast landscapes. The capability to refill quickly—often within seconds—allows operations to persist over hours or days, a necessity when fighting large wildfires in rugged terrain where ground tactics cannot keep pace. This class of aircraft is designed for endurance and reliability, with safety margins and verification processes that ensure they can operate in challenging weather and at altitude while maintaining effective water delivery. The scale of what these machines can accomplish expands the tempo of response, reducing the time between detection and suppression and, with intelligence on the fire’s behavior, enabling crews to plan for containment strategies with greater confidence.

Alongside these monumental airframes, a second thread of innovation runs through a growing family of mid-sized fixed-wing firefighting aircraft. These platforms are more versatile than their larger cousins, optimized for versatility, rapid deployment, and efficient operation in a wide range of environments. Their design emphasizes modular payload systems, allowing operators to tailor the aircraft to specific mission profiles—forest firefighting, urban suppression, search-and-rescue, or casualty evacuation. Avionics suites in these aircraft have become increasingly sophisticated: integrated navigation, automated flight planning, and real-time data links that connect the cockpit with ground command centers. The result is a fleet that can be rapidly marshaled, reconfigured, and deployed with a minimum footprint of downtime, a crucial advantage when every minute can mean the difference between a manageable incident and a catastrophic one. The domestic development approaches in many nations reflect a strategic shift toward mission specificity and domestic capability, symbolizing a broader industrial policy in which air safety and emergency readiness are closely tied to a country’s broader technological sovereignty.

The evolution, however, is not confined to fixed-wing giants. A new generation of low-altitude unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has become an indispensable companion to traditional firefighting aircraft and ground crews alike. These drones operate at the scale of city blocks and hillside terrains, entering spaces that would be unsafe or impractical for manned aircraft or ground units. Heavy-lift drones and vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) systems now serve as “technical wings” in dense urban environments, delivering extinguishing agents, suppression bombs, and essential equipment with remarkable precision. The shift toward autonomous or semi-autonomous platforms is driven by the need to minimize human risk while maximizing reach and accuracy in challenging settings. In city demonstrations, drones outfitted with flat-wound motors and advanced stabilization have proven capable of hovering in gusty winds, maintaining a steady platform for targeted releases. While the artistic image is of a drone delivering a canister to a high floor or a rooftop, the practical reality is a nuanced choreography of wind, drone control, payload dynamics, and the ever-present need for situational awareness.

The most transformative trend, perhaps, lies in the integration of air, ground, and space technologies into a cohesive command-and-control ecosystem. Integrated “air-ground-space” monitoring and operational systems enable a rapid, layered understanding of an incident. Drones equipped with infrared thermography, LiDAR, and AI-driven smoke-detection algorithms become eyes that do not tire and legs that do not fatigue. They provide early detection, map fire spread, and analyze terrain to identify choke points, fuel sources, and potential ingress routes for ground crews. This data becomes actionable intelligence, turned into predictive models that guide decision-making under pressure. The shift from reactive to proactive response is not merely a matter of speed but a difference in capability: the ability to anticipate a fire’s trajectory and to position resources in ways that optimize safety and effectiveness. It is a transformation that owes much to advances in sensors, data processing, and real-time communication networks that keep the air, the ground, and central command on the same page.

In medical emergencies, the impact of aerial systems has reached beyond fire suppression to the rapid creation of life-saving networks. Across urban and rural landscapes, drone networks are expanding the reach of critical care through what some call rapid-response intervals—the idea that essential supplies, such as AEDs or blood samples, can be delivered within minutes regardless of road congestion or remote geography. In some places, pilots and planners are implementing concepts like compact, distributed “rescue circles” that ensure that even if a single access point fails, another can quickly fill the gap. These systems are modern extensions of a historical mission: to bring care to the patient when time is scarce, when the traditional ambulance might take too long, or when terrain makes ground transport perilous. The emerging model treats air as a vascular system for emergency medicine, delivering not only water or suppression agents but also critical care tools and materials that can stabilize life in the crucial minutes before on-scene treatment and hospital care.

To comprehend how these innovations coalesce, it is useful to imagine an emergency response ecosystem that is intelligent, adaptive, and resilient. The heavy-lift platforms ensure that large-scale fires, particularly those that threaten remote forested areas or coastal zones, can be attacked with sustained force and rapid refueling cycles. Medium-sized firefighting aircraft complement these operations by delivering precision drops and by enabling rapid escalation or tapering of response as conditions dictate. Drones function as continuous eyes in the sky, providing higher-frequency surveillance and precision delivery, while thermal imaging and LiDAR offer the analytic backbone that supports both suppression and evacuation planning. All of this sits within a network that binds air operations to ground units and to medical teams, enabling a more coordinated and safer execution of missions.

The social and policy dimensions of this evolution are as important as the mechanical innovations. Countries investing in domestic aviation industries and integrated emergency systems are investing in resilience—geographic resilience, operational resilience, and human resilience. Operators of these systems must balance the demands of safety, efficiency, and cost. They must also navigate regulatory frameworks that govern airspace use, interagency cooperation, and import/export controls for sensitive technologies. Training and certification become enduring commitments, not one-off requirements. The path from simple piloted flight to automated, data-driven operations requires ongoing investment in people—pilots who are comfortable with complex avionics, emergency medical technicians who can ride the edges of speed and precision, and data scientists who can translate sensor streams into actionable decisions during the heat of an incident.

In weaving together these threads, we can see a lineage that starts with the Wright brothers’ breakthrough and flows through the decades into a modern scene where planes and drones are not separate from rescue and firefighting but central to how we think about hazard, risk, and relief. The stories embedded in today’s fleets are not about a single hero or a singular invention. They are about a continuum—one that honors early explorations of flight, learns from the battlefield and the frontier, and then applies those lessons to the most urgent human needs: saving lives and protecting communities. The moral of this evolution is clear: aviation’s true payload is not only water or equipment dropped from above, but the ability to bring time to the side of someone in danger, to place expertise at the precise moment of need, and to knit together a network that makes rescue faster, smarter, and more humane.

As nations advance, the horizon for fire and rescue aviation expands further. The models that succeed will blend cutting-edge sensors, adaptive payloads, and smarter autonomy with a robust framework for safety, training, and interagency cooperation. The aim is not to replace human teams but to augment them—extending reach, reducing risk, and accelerating the tempo of intervention. In that sense, the modern fire and rescue aircraft are not merely tools evolved from a historic invention; they are the living embodiment of a continuous, shared human project: to safeguard lives and communities through the disciplined art of flight, guided by data, driven by duty, and sustained by the will to act decisively when danger fills the skies.

For readers exploring professional pathways in this field, the chapter also speaks to careers built on continuous learning and credentialing. A strong foundation in safety-critical competencies, coupled with formal training in modern air operations, becomes the bridge between curiosity about flight and impact in emergencies. The profession increasingly rewards those who can integrate flight hardware with software analytics, who can interpret a thermal image while coordinating with a rescue team on the ground, and who can adapt quickly to evolving conditions at the edge of a wildfire’s reach. In that context, pursuing formal qualifications in fire safety and emergency management—alongside hands-on experience in aerial operations—becomes a practical and meaningful journey. the vital role of fire safety certificates in your career journey

Yet the most compelling takeaway is that the story of fire and rescue aircraft is a story about systems thinking. It is about the deliberate assembly of hardware, software, human skill, and organizational processes into a cohesive whole that can respond with speed, accuracy, and compassion. The enormous, often silent work of engineers who design airframes to endure abuse, pilots who master the tempo of rapid mission planning, ground crews who manage stochastic terrain and weather, and medics who must stay calm under pressure—all of this converges when a siren sounds and a plane takes to the air. It is a narrative that honors a long arc—from the first flights that hinted at what was possible to the sophisticated, multi-layered networks that now define how we rescue people from wildfires, urban conflagrations, and remote emergencies alike. In this sense, the skies are not just a stage for spectacle; they are the critical corridor by which life is saved, and the evolution of that corridor continues to unfold as technology, policy, and human resilience intersect.

External resource: https://www.china.org.cn/china/2023-08/14/content_79658925.htm

Final thoughts

The journey from the Wright Brothers’ first flight to today’s sophisticated firefighting aircraft showcases an incredible evolution of technology driven by necessity. Each advancement not only improved the means of rescue but also redefined strategies to combat one of nature’s most destructive forces—fire. As we continue to innovate and optimize aerial responses to emergencies, the potential for more effective and efficient fire and rescue operations grows, ensuring that we’re better equipped to protect lives and property from disaster.