In any fire emergency, the instinct to save a life can be overwhelming, prompting crucial decisions that balance urgency with safety. Understanding when it is appropriate to rescue someone trapped in a fire is essential for both potential rescuers and those who might find themselves in such a dire situation. This article delves into the critical aspects of assessing safety before attempting a rescue, outlines key life-saving protocols, and emphasizes the importance of calling emergency services when necessary. By comprehensively addressing these topics, we aim to equip you with the knowledge to make informed decisions during fire emergencies, safeguarding both your life and others.

In the Smoke: The Delicate Calculation of Rescue in a Fire Emergency

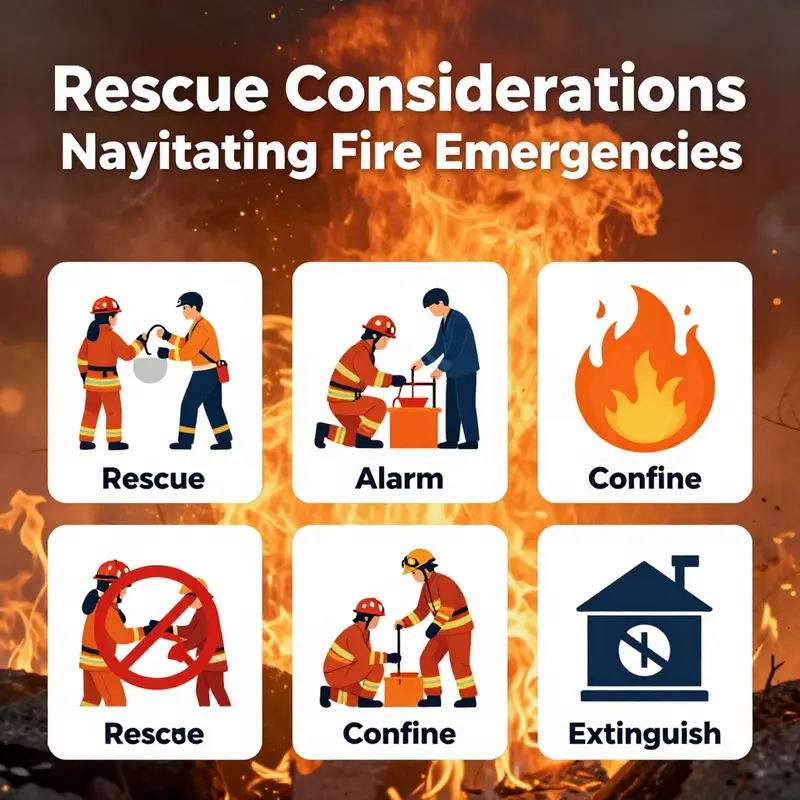

When a fire erupts, the impulse to act is powerful. It is a moment where courage and caution intersect, and the best choice is not always the most dramatic action but the action that preserves life while preserving your own safety. The core question, should I rescue a person from a fire, demands more than a gut reaction. It demands a clear-eyed assessment of risk, an understanding of what you can do safely, and a readiness to involve professionals who have the training and equipment to manage what you cannot. In that moment of heat and chaos, a bystander becomes a decision maker, balancing the instinct to help with the reality that entering a burning structure carries extreme hazards. Heat can sear skin and eyes, visibility can vanish in smoke, and structural elements may fail without warning. It is not merely the flames one must fear, but the invisible assault of smoke and the sudden collapse that can trap you as easily as it traps those inside. This is why the most practical, life-preserving mindset begins with safety as a boundary. If you are not trained or equipped to handle the dangers of a fire, stepping into the building is not a heroic risk. It is a mistake that can cost two lives instead of one. The safety framework is simple in language but demanding in discipline: prioritize your safety first, call for help, and act only within the limits of what you can do without becoming another victim. The learning that follows does not diminish courage. It sharpens it by turning instinct into informed action and by teaching how to move the rescue from impulse to plan. The guidance widely taught by authorities such as the U.S. Fire Administration and the National Fire Protection Association emphasizes a structured response rather than a single act of bravery. If a person is in immediate danger and you can reach them without placing your life at risk, you may perform a rescue. But you should never sacrifice your own life to save another. The principle is not a call to passivity; it is a call to intelligent intervention that recognizes the limits of a bystander and leverages professional help as promptly as possible. This is the moral architecture of smart rescue in a fire: act where you can, but always within the perimeter of your safety. From this principle flows a practical method, often condensed into four steps that begin with action and end with accountability. The order is not the same as heroic theater; it is a sequence designed to maximize outcomes for everyone involved. First, rescue if it is safe. Second, alarm by calling emergency services and providing precise location data. Third, confine the fire by closing doors where safe to do so, slowing its spread and protecting escape routes. Fourth, extinguish only if the fire is small, you have training, and you possess the right tools. Each step reinforces the others and makes the most of what a bystander can contribute without turning a peril into a tragedy. The recognition that smoke inhalation is the leading cause of fire fatalities, not direct flame contact, reframes the decision-making process. NFPA research consistently highlights how quickly smoke can overwhelm a person, disorienting, suffocating, and hindering judgment long before flames reach the body. A door blocked by smoke is a door to safety, not merely a barrier to a flame. This reality undercuts the impulse to race inside with little preparation and redirects energy toward methods that preserve life without compromising it. It also clarifies why training matters. The skills to navigate a smoke-filled corridor, identify a safe exit, or use a fire alarm effectively are not innate for most of us. They are learned, practiced, and refined through formal preparation. The value of training is not merely technical; it is cognitive. Training helps a person translate fear into action, to ask the right questions at the right moment, and to remember the sequence that can save lives when adrenaline is highest. For those who seek a grounded path toward preparedness, practical training—whether through community courses, workplace programs, or formal certification—transforms uncertainty into capability. You can learn how to test doors safely by using the back of a hand to gauge heat, how to crawl low to minimize inhalation exposure, and how to communicate clearly with others who may be disoriented or helpless. These habits, built before an emergency, become reflexes when the room fills with smoke. They also shape expectations for what it means to rescue in a way that aligns with the broader goal of safety for all. When a fire threatens, your immediate responsibility is to yourself and to those you can help without stepping beyond your safe boundary. If a person is within reach and conditions permit a guided, short movement toward the exit, you may lead them out. The guidance is precise: do not push into areas where heat, radiant energy, or sudden collapse could yank you back. Do not attempt to drag someone down stairs if you encounter a closed door that is densely hot to the touch. And never disregard the need to call for professional support, as responders are trained to navigate the unstable environment, manage hazards that bystanders cannot, and perform rescues in ways that minimize risk to the public. The philosophy behind rescue in a fire is not about one moment of grand action; it is about the orchestration of safe, incremental steps that tighten the chance of survival for everyone involved. When a bystander sees an occupant who is disoriented, shouting or crying, the impulse to deliver guidance can be powerful and life-saving, provided it happens within a safe boundary. A calm directive, spoken with urgency, can help an individual identify the safest route to exit and avoid panicked movement that could worsen injuries. If you attempt a rescue within the building, you do so with the awareness that a fall could create another victim. The door you choose to open, the wall you lean against, and the path you take must all be examined for risk. A single bad decision can turn a rescue attempt into a trap that is nearly impossible to escape. This is why the guiding principle remains constant: safety first, safety second, safety always. The emphasis on safety does not remove the moral charge of helping others; it reframes it. You are not abandoning someone by stepping back to call for help or to wait for trained personnel. You are preserving the possibility of a future rescue by ensuring you are able to participate in further actions, such as aiding others to move away from danger or guiding them toward an exit. Those acts of assistance—shouting directions, locating companions, or directing people toward a safer corridor—are often the most accessible and impactful forms of bystander intervention. If you see others nearby who are unable to move, such as elderly individuals, children, or people with disabilities, you should assist them if you can do so without compromising your own safety. The more people who exit safely, the less strain responders face and the greater the chance that everyone can be accounted for. In many cases, this means using established routes and avoiding stairwells or corridors that become chokepoints as smoke fills the building. It means keeping voices calm and guiding people toward the most direct and safe exit, not toward a sacrifice of safety in a misguided sense of heroism. The practical reality is that most successful outcomes involve collaboration with the people around you, not solitary acts of bravado. A bystander can influence the safety of an entire scene by communicating clearly, maintaining a steady pace, and avoiding actions that create confusion or new hazards. This collaborative approach, built on the RACE framework, is designed to yield the safest possible outcome under chaotic conditions. If you apply the four-step method consistently, you create a predictable rhythm that responders can anticipate and build upon. Rescue becomes not a reckless entry but a conscious, measured intervention that respects the limits of layperson capabilities while still leveraging the crucial first hours when a life might be saved. The best way to prepare for such moments is to engage with credible training before an incident occurs. Practical, hands-on training equips you with the instincts and routines that keep your decisions aligned with safety. It is not merely about how to operate a tool or a technique; it is about how to think under pressure. The discipline of readiness transforms fear into structured action, and that transformation is what makes a difference when smoke begins to obscure sight and doors become more than mere barriers. For readers seeking a concrete pathway to preparedness, consider resources that focus on core fire safety competencies and ongoing practice. There is value in learning how to recognize early warning signs of danger, how to communicate clearly under stress, and how to maintain composure long enough to get yourself and others to safety. Even if you never need to perform a rescue, the skills gained through training empower you to notice hazards sooner, navigate risks more effectively, and act with a calm sense of purpose when seconds count. The decision to rescue, then, sits at the intersection of courage and prudence. It is a decision that weighs the immediate danger against the potential to preserve life, including your own. It asks whether a rescue is truly feasible given the conditions, whether the person in danger is reachable without creating new hazards, and whether professionals can be summoned to take over quickly. It invites reflection on what you would do in your own home, workplace, or community. The answer is rarely a single verb but a careful sequence that aligns with established safety principles. By embracing the ethic of safety-first rescue, you honor the very reason firefighters and first responders exist: to enter perilous environments with specialized training, tools, and support so that lives can be saved with a coordinated, professional response. In the end, the question is not only about a rescue in the heat of the moment; it is about cultivating a mindset that sees danger clearly, acts within capability, and remains steadfast in the belief that life is the priority—while recognizing that the highest form of bravery may be to wait for the right help and to make space for others to exit safely. For those who want a structured path to internalize these principles, ongoing education and certified training provide a reliable foundation. This preparation allows you to distinguish between acts of impulsive heroism and informed, protective intervention that truly serves the goal of saving lives. If you seek further guidance that anchors these ideas in practice, you can explore validated resources and training opportunities, such as the Fire Safety Essentials Certification Training, which translates these principles into actionable skills and rehearsed responses. As you read, keep in mind that the most powerful rescue often begins with a calm assessment, a timely alarm, and a clear channel for others to reach safety. For those who wish to deepen their understanding of these concepts, credible organizations and training programs offer pathways to become more confident and capable in the face of fire danger. The right action is the one that protects life while preserving the chance for everyone to be rescued by professionals who can operate in environments far beyond the reach of untrained bystanders. External guidance from established safety authorities remains essential, and it is through adherence to these standards that communities strengthen their resilience against fire hazards. For more detailed, authority-backed guidance, see the NFPA at https://www.nfpa.org/.

Acting with Care: How Life-Saving Protocols Shape Your Decision to Rescue Someone from a Fire

When a fire erupts, the impulse to leap in and pull someone to safety can feel overwhelming. Yet wisdom in an emergency grows from a careful balance between courage and caution. The question isn’t simply, Can I rescue? It is: Is it safe for me to act, and if not, what is the most effective way I can help without becoming another casualty? The answer is anchored in life-saving protocols that prize every life while prioritizing your own safety. This is not a theoretical exercise but a practical discipline—the kind that rests on clear assessment, disciplined action, and a deep respect for the limits that danger imposes. In the moment, those limits may change with each passing second, as heat intensifies, smoke thickens, and structural integrity shifts. The guiding principle remains consistent: do not sacrifice your own life in a bid to save another. If you can reach someone without exposing yourself to unacceptable risks, you should act. If the path ahead carries a distinct likelihood of trapping you inside, you must step back and call for professional help, signaling the location and condition of the person in peril. The broader framework that shapes such decisions is the Rescue, Alarm, Confine, Extinguish sequence—often remembered by its acronym, RACE. This quartet is not a rigid recipe but a mental model that keeps the bystander oriented amid chaos. First, Rescue anyone in immediate danger if you can do so safely. Second, Alarm by alerting the fire department as swiftly as possible. Third, Confine by closing doors to slow the fire and limit smoke spread, only if doing so does not place you at greater risk. Fourth, Extinguish the fire only if it is small, the space is clear, you are trained to use a extinguisher, and you have a safe escape route behind you. When you hold this sequence in your mind, you begin to transform a surge of heat and smoke into a structured set of choices. It becomes less about heroics and more about precise, life-preserving action. Yet the reality of a living room-sized blaze or a stairwell choked with acrid smoke is far from a classroom demonstration. It demands an intimate respect for danger and a sober assessment of your own limits. The bystander’s instinct to help is powerful and noble. It is precisely because it is powerful that it must be guided by training, planning, and situational awareness. In practice, this means recognizing that a small fire with a clear, direct path to the exit is a different problem from a rapidly spreading blaze that fills corridors with toxic smoke. The difference is not just about the amount of fire but about the line of retreat, the visibility of exits, and the energy you bring to the scene. A robust decision-making approach hinges on three intertwined habits: calm assessment, rapid communication, and conservative risk evaluation. Staying calm is the first and simplest act you can perform. Panic is a force multiplier for danger; it clouds judgment, accelerates breathing, and can cloud your sense of the distances involved. The moment you feel fear rising, take a slow, deliberate breath, count to four, and let your attention return to concrete observations—where is the safest exit? Is the fire moving toward this exit? Can you reach the person without forcing yourself into the path of heat and smoke? The ability to observe with clarity often determines whether you rescue or evacuate. In many fires the most dangerous condition is not the flames themselves but the smoke that reduces visibility and robs you of your sense of direction. Smoke can travel along the ceiling, hug walls, and creating pockets of oxygen-depleted air that catch and intensify heat. The first use of this awareness is to orient toward an exit that remains reachable, keeping your back to the path you used to enter so you can retreat with your eyes toward the way out. If someone is trapped, you must decide whether to attempt a rescue, and if so, how to do so without compromising your own safety. This is where the precise knowledge of your environment matters. A familiar building, a route you have practiced, and a sense of how the fire tends to move can be a critical advantage. If you are in a structure you do not know well, it may be safer to stay with the principle of safe evacuation rather than risk entering a compromised space. The moment you detect you cannot safely reach the person, you switch from a rescue mindset to a notification mindset—activate the nearest fire alarm if you have not already done so, and call the emergency number with a clear description of the location, the fire’s size, the layout of the building, and the person’s approximate location. The value of an immediate, accurate report cannot be overstated. For the person who might be trapped, time is both a friend and a variable. The faster help arrives, the better the chance of a safe outcome. Yet time is also a limiter—the faster you act, the more you must consider whether your own action will open a new corridor of danger for others. The phrase every second counts is not a cliché in a fire scene; it is a reminder that delays can convert a recoverable situation into a catastrophic one. With these realities in mind, the bystander becomes a conduit of information, a relay between the danger on the ground and the resources of professional responders. The call for help should be precise: give exact locations, describe any obstacles that hinder exit routes, note if the person is conscious, and mention any medical needs such as age-related limitations, disabilities, or injuries that could affect their ability to move. If you decide to act on a rescue, you must do so with a plan for your own exit. A common, real-world mistake is to pursue a person through a doorway or stairwell that becomes a choke point or a trapdoor into a deeper hazard. Your plan should always include an escape route behind you, a way to retreat if the space suddenly becomes untenable, and a contingency if your initial approach fails. The rescue itself is rarely a dramatic sprint through a sea of flame. It is often a careful, deliberate approach that minimizes time in smoke while maximizing the chance of reaching the individual and guiding them toward an exit. In some circumstances, reaching a person at arm’s length through thick smoke with a clear, unobstructed path is feasible. In others, it is not. When it is, your technique should leverage communication and reassurance as much as physical manipulation. Shouting calming instructions can help the person stay oriented while you maneuver to a safer corridor. If you can physically support someone who cannot move, you should offer your arm or shoulder as a stabilizing contact and lead them toward the exit. Even then, you must continuously reassess whether the act remains safe. You might discover that pulling someone who is unconscious or fainting could place you both at risk, especially if you cannot secure a reliable grip or you encounter structural instability. These are the moments that crystallize why rescue is conditional on your capacity to act without becoming a second victim. The ethical dimension of rescue also requires attention. When you see someone nearby who cannot move or is less able to evacuate—an elderly person, a small child, or a person with a disability—your impulse to help becomes even more important. If you can do so safely, you should assist them. This does not obligate you to assume an impossible burden or to endanger yourself. It is a call to contribute to the broader safety-net in a way that respects both your limits and theirs. In this sense, bystander intervention is a cooperative process that depends on clear signals, such as audible alarms, visible exit signage, and a calm, guiding voice that helps others find their way out. Training is the backbone of responsible bystander action because it translates instinct into reliable, repeatable practice. The more you train, the more you recognize patterns in fires—the way heat concentrates along a path, the way smoke travels across a room, the ways doors and windows can influence airflow. Training helps you interpret these signals quickly and act with confidence rather than hesitation. It also helps you understand what to do when the situation exceeds your capabilities. Even when you cannot rescue, you can still play a critical role by alerting others, guiding people away from danger, and providing a steady presence that reduces panic. The importance of professional response cannot be overstated, and the sooner professionals arrive, the greater the likelihood of a favorable outcome for the vulnerable individuals who may still be inside. In the meantime, consider how you might prepare for such moments in everyday life. Regular participation in fire-safety drills, familiarization with escape routes at work and home, and practice with basic fire-extinguisher techniques can sharpen your decision-making in real time. If you are seeking practical avenues to deepen this preparedness, resources like fire safety essentials certification training can provide structured learning that translates into confidence during emergencies. Such training supports a disciplined approach to RACE, with scenarios that mirror the pressures of a genuine blaze. It is reasonable to want to do more than evacuate when a person is in danger, yet it is essential to anchor that impulse in a clear assessment of risk, a coherent plan for action, and a steadfast commitment to preserving life—your own and others. The bystander who practices, who voices a plan, who moves deliberately toward safety rather than impulsively toward danger, becomes an effective force for good. That effectiveness does not come from bravado but from a grounded, repeatable approach to safety. The line between heroism and recklessness can be thin, and it is precisely the purpose of life-saving protocols to define that line in advance, before the heat and smoke blur judgment. When you encounter a fire scene, you are not merely an observer; you are a participant in a chain of actions that connects civilian responders to professional responders. Your actions can either shorten or prolong the time it takes for rescue to occur. You can be the one who preserves a doorway of escape, who reduces the friction of a chaotic environment, or who simply ensures that someone who needs help knows that help is nearby. In the long run, the most meaningful rescue is often the one that never requires you to enter the danger zone at all: the rescue that happens through early alarm, through controlled containment of the blaze, and through a clear, accessible path to safety for every person in the building. This is the core of the life-saving protocol: act with care, act within your limits, act to maximize the chances that every life involved emerges from danger intact. The chain of action—Rescue when safe, Alarm promptly, Confine where possible, Extinguish only with proper training and equipment—gives you a framework that reduces chaos to manageable steps. It also honors the reality that training and preparation can transform fear into precise, purposeful conduct. In the end, the most dependable decision you can make about rescuing from a fire is the decision to prioritize safety, to activate help without delay, and to remember that every moment you keep yourself out of harm’s way is a moment you preserve your ability to assist others when the path becomes clear. As you move forward through the rest of this article, you will see how this framework connects to broader fire-safety strategies, including the critical role of public education, the value of training, and the ways in which communities can develop resilient responses to fires. If you want to deepen your preparedness, consider engaging with resources such as fire safety essentials certification training, which helps translate these principles into practical skills. And as you reflect on the delicate balance between courage and caution, keep in mind the guidance from established authorities that emphasizes protecting lives while never placing your own life at unnecessary risk. For more authoritative, up-to-date guidance, refer to NFPA’s fire-emergency guidance, which offers comprehensive recommendations that align with the principles described here: https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research/News/2023/10-18-2023-What-to-do-in-a-fire-emergency

null

null

Final thoughts

Navigating the decision to rescue someone from a fire is a complex process that demands a clear understanding of safety, protocols, and the appropriate steps to take. Prioritizing your safety while recognizing when to act or alert professionals can potentially save lives. The RACE principle provides a structured approach to addressing emergencies effectively. In every situation, remember that while the urge to save is compelling, your safety must always come first. Equip yourself with knowledge and prepare for emergencies to make informed and life-saving decisions.