As fires rage with uncontrollable intensity, the question of why some individuals remain trapped often arises. Understanding these intricacies is vital, particularly for individuals in positions of responsibility, such as auto dealerships, fleet buyers, and business owners, who must prioritize safety in their environments. Through four essential areas—delayed detection, ineffective evacuation techniques, rapid smoke and heat spread, and structural flaws—we can glean key insights into the dangers that thwart rescue efforts in fiery emergencies. Each chapter will unravel critical factors that contribute to rescue failures and offer insights on preventative measures.

Delays in Detection and Response: How Timing Shapes Fire Outcomes

When a fire begins, the earliest moments determine what comes next. Delayed detection allows flames to spread and smoke to fill spaces faster than occupants can react. Sleep, alarm response fatigue, and mobility limits magnify risks, especially for the elderly and those living alone. This chapter explains why seconds matter, how alarms, doors, and routes to safety interact with everyday environments, and why misjudgments about elevators and exiting strategies often lead to worse outcomes. It then outlines practical steps for prevention and preparedness: install and maintain working smoke detectors, rehearse evacuation plans, keep exits clear, test doors for heat before opening, crawl under smoke, stay low, and use stairs rather than elevators during a fire. It also emphasizes the role of design choices and policy in reducing the safety gap, including better detector coverage, clear signage, unobstructed corridors, and safe egress paths. Readers are encouraged to translate these insights into daily routines, family discussions, and community training so that the earliest seconds of danger become opportunities for safe escape rather than fatal delay.

Unsafe Evacuations: Real Risks in Fires

Fire does not simply burn; it distorts perception, pressuring people to rapid decisions. In a crisis, the instinct to survive is strong, yet that instinct can collide with flawed choices that turn a smoke filled building into a trap. The chain of events during a fire rarely hinges on a single mistake. Instead, it is the accumulation of unsafe evacuation behaviors driven by fear, confusion, and hazards that elevates risk and narrows chances of rescue. Elevators promise speed but can fail during power loss or heat; stairwells can fill with smoke, reducing visibility and mobility. The lack of practiced routines and clear guidance can convert fear into risky improvisation. Preparedness, architectural resilience, and intelligent guidance can transform evacuation into a reliable process that buys time for rescue. The best outcomes occur when design supports safe egress, training builds muscle memory for safe movement, and technology provides real-time route guidance that adapts to evolving conditions.

This is not just about exits but about the interaction of people and their environment. If exits are blocked or compromised, even informed occupants may be overwhelmed by crowding or heat. Regular drills, low crawl techniques, door temperature checks, and clear signage help shift behavior from panic to deliberate action. Safety is enhanced when occupants know how to verify a door’s heat, how to choose the safest stairwell, and how to move as a coordinated flow rather than as isolated individuals. In addition, planners and responders can use building data and predictive models to anticipate bottlenecks and guide dynamic evacuations, rather than rely on fixed plans that may become unsafe as the fire progresses.

The overarching takeaway is that safe evacuation results from an integrated system of design, training, and real time information. Elevators should be avoided during fires; stairwells must be reliable and protected by fire doors; exits must remain accessible even under heat and smoke. With this approach, the odds of timely rescue increase, and the consequences of a fire are less dire for those who act calmly and follow tested procedures. The research literature points toward practical steps that communities and building managers can implement today to reduce the risk of unsafe evacuations and improve protective outcomes in the worst of fires.

When Smoke Rises Faster Than Help: How Rapid Fire Spread Shapes Our Ability to Rescue in Residential Fires

The moment a fire starts in a home, a silent clock begins ticking. What determines whether a person makes it out alive is not only the strength of a response team or the luck of the moment, but the speed with which smoke and heat flood the living space. Rapid smoke and heat spread can turn a simple escape route into a grim obstacle course in minutes, often before anyone outside the building even realizes a crisis is unfolding. In residential settings, where most fires begin and where many victims are alone or partially immobile, the dynamics of this rapid progression become the central force shaping survival. The physics behind it is both straightforward and merciless: hot gases generated by the flame rise and accumulate near the ceiling, creating a smoke layer that thickens and thickens as the fire consumes more fuel. As the smoke builds, it robs air, reduces visibility, and delivers a surge of toxic gases. For anyone trying to navigate the hallways, stairs, and doors, the air becomes a hidden trap. The person nearest the floor may be able to breathe more easily, but the same low air space is the zone where doors feel cooler to the touch and where feet can find a floor that remains solid enough to stand. This paradox—danger above and danger below—forces a difficult balancing act for escape, choice, and timing. In real homes, the consequence is often a loss of the window of opportunity that separates a swift rescue from a long, arduous, or impossible one.

A substantial strand of research emphasizes that older adults face a disproportionately higher risk in such conditions. A 2021 study by M Runefors underscores how physical and cognitive limitations compound the danger. Slower reaction times, reduced mobility, and diminished stamina can turn a few crucial seconds into a fatal delay. When the clock starts counting in a rapidly evolving fire, time stretches in the wrong direction for someone who may already be counting their breaths more carefully than their options. The study frames this as not merely a vulnerability of age, but a consequence of how fast the environment can become lethal. The smoke layer rising through a building is not a constant backdrop; it is a dynamic force that reshapes the interior space in a heartbeat. This is why early detection and immediate protective actions are so vital. The speed of smoke and heat progression can outpace human response and even the best-organized rescue efforts. When a family member is alone in a single-occupancy dwelling, there may be no one to sound an alarm, to attempt a rescue, or to guide the path to safety. In such cases, survival hinges on anticipatory behavior and practical know-how built into daily life.

The danger of rapid spread is magnified in homes that lack robust fire safety measures or that have design features which inadvertently accelerate danger. Dense walls without compartmentalization, doors that do little to slow smoke, or maintenance gaps that allow flames to leap from one room to another can turn a contained flame into a burgeoning inferno within minutes. In the context of recent incidents, media and post-event analyses spotlight how quickly smoke can fill stairwells and corridors. The mathematics of residence fires shows that what starts as a localized flame can trigger a chain reaction: a room fills, a hallway becomes a trap, and visibility drops to near zero as the air thickens with particulates and toxic gases. A crucial corollary is that the very routes people might try—the stairs or the corridor—can become the same pathways smoke uses to reach more of the home. When this happens, the stairwell becomes a conduit for danger rather than a safe exit route.

The human dimension of rapid smoke spread also carries a heavy emotional weight. Panic, fear, and the instinct to protect personal belongings can cloud judgment at moments when the correct action is straightforward yet hard to execute. The reaction of freezing in place or attempting to gather valuables delays evacuation, buying a few seconds for a blaze outside to intensify into a rapidly expanding heat zone. When the environment shifts from a familiar living space to a cauldron of heat and toxic fumes, instinctual actions can become counterproductive. The cognitive load of crisis management—remembering to stay low, crawl, cover the mouth, and test doors for heat—competes with the stress of trying to locate a child, a parent, or a caregiver. In such torrents of sensory overload, the most robust defense is prior preparation, not last-minute improvisation.

Education, though, is not a magic shield against the physics of a rapidly evolving fire. It is a shield against the paralysis and missteps that can follow. The simple protective actions taught in fire safety literature have a disproportionate impact when smoke spreads quickly. Staying close to the floor keeps the person in air that is less laden with heat and toxic fumes. Crawling enables a person to move through a corridor while the smoke climbs above the head, creating a clearer path to a door that might lead to a safe haven or a staircase that remains passable. Covering the mouth and nose with a damp cloth can filter some particles and make breathing more bearable, though it is not a substitute for rapid exit. The stark reality is that in the time it takes to decide to fight the fire or to attempt a rescue, the interior of the home may shift from a breathable space to a choking, overheating conduit. Each moment, the room grows more hostile; each breath becomes costlier; each step toward an exit becomes a test of endurance against the heat.

While the science of smoke movement explains much, it is the synthesis of design, behavior, and response that shapes outcomes in practice. The 2025 incidents in dense urban housing remind us that even buildings that look sturdy on the outside can harbor vulnerabilities inside. A structure over forty years old, with maintenance issues and insufficient fireproofing, can allow fire and smoke to move through fractures and joints with greater ease. Blocked exits, ineffective sprinklers, and missing fire doors can turn a potential fire short course into a long, suffocating ordeal. In a scenario where hundreds of occupants might be affected, the speed of spread translates into a narrowing window for rescue and a widening circle of risk for those still inside. The same dynamics affect emergency responders. Aerial ladders and modern gear are powerful, yet even these tools are tested by the sheer intensity of heat, falling debris, and the structural instability that accompany rapid fire progression. In this context, it is easy to see why some people remain unrescued—not from lack of courage or capability, but from the relentless tempo of the fire and the constraints it imposes on every route to safety.

Within this interplay of physics and human factors lies a core lesson for prevention and preparedness. Early detection by smoke alarms, prompt alarm transmission, and clear evacuation plans can provide precious minutes when every second matters. But even with detectors functioning correctly, the knowledge of how to respond when heat and smoke surge through a home is crucial. The reflex to assess door temperature before attempting a passage, the discipline to stay low and move continuously rather than pausing to collect belongings, and the decision to abandon a room the moment it becomes uneasy are actions that can determine whether a person progresses toward safety or is consumed by the smoke. These actions are not abstract prescriptions; they are the practical applications of years of safety training translated into seconds of decisive behavior. This is why programs that emphasize hands-on practice and drill-based learning matter. They turn theoretical guidance into muscle memory, increasing the odds that people will act correctly when the fire arrives with violent speed. For readers seeking concrete steps to strengthen preparedness, the literature points to structured training—a path that connects knowledge to action in the moments when it counts most. See the discussion of training programs and essential preparedness steps in resources like Fire Safety Essentials Certification Training, which translates life-saving concepts into accessible practice for households and communities. Fire Safety Essentials Certification Training

The broader takeaway extends beyond the individual. Rapid smoke spread highlights a need for building codes, fire protection engineering, and urban planning that anticipate how homes burn and how quickly occupants lose options. It underscores the value of compartmentalization, which can slow the spread of smoke and heat and preserve safer zones within a dwelling. It reinforces the importance of reliable ventilation control, fire doors that perform as barriers rather than weak links, and functional sprinklers that can buy precious minutes by interrupting rapid flame growth. It also suggests a critical, less glamorous role for policy: ensuring that retrofit programs target aging housing stock, that accessibility considerations are embedded in egress design, and that maintenance regimes maintain the integrity of life-saving systems. In other words, rapid smoke spread does not just test the courage of residents; it tests the resilience of the built environment and the adequacy of the systems designed to protect it.

As we confront this reality, it is helpful to keep in mind the human stories that underlie the data. When older adults confront a blaze, their slower response times do not mean a lack of will to escape. They reflect the real-world constraints of aging bodies and the cognitive load of a crisis. The most hopeful path forward blends three strands: preventing fires from reaching a point where smoke accelerates beyond control, enabling immediate and effective self-evacuation when a fire starts, and ensuring that responders can reach and rescue those who remain. Each strand reinforces the others. If detectors wake households early, if occupants know how to move with the smoke rather than against it, and if design modifications keep escape routes open, then the probability of rescue rises. Conversely, when any one strand is weak—when detection is delayed, or when occupants hesitate, or when doors and stairs fail to provide safe egress—the chance of a successful rescue diminishes sharply.

In everyday terms, rapid smoke spread is a reminder of the fragility of safety in the home. It asks us to act not only with courage but with foresight: to install and maintain detectors, to practice clear exit plans, to learn the protective habits that heat and smoke demand, and to advocate for homes and neighborhoods that slow the flame’s advance. The knowledge is not only a public safety message; it is a personal mandate to prepare, practice, and protect those who are most vulnerable when the clock starts ticking. The science explains why some people cannot be rescued in certain fires, but the public response—education, preparedness, and robust safety design—offers a path to change that story. As a shared responsibility, it places family, neighbors, and communities in a position to reduce risk before a fire starts and to increase the odds of a safe outcome when it does. External research continues to illuminate the limits of human and rescue capacity, reminding us that the real guardians of resilience are the routines we practice long before the smoke arrives. For anyone seeking a deeper dive into how survival and evacuation unfold under rapid fire progression, the body of work is clear and consistent, pointing to the same conclusion: preparedness matters, and the speed of the fire makes preparedness a lifeline rather than a luxury.

External resource: https://doi.org/10.1080/17457159.2020.1839869

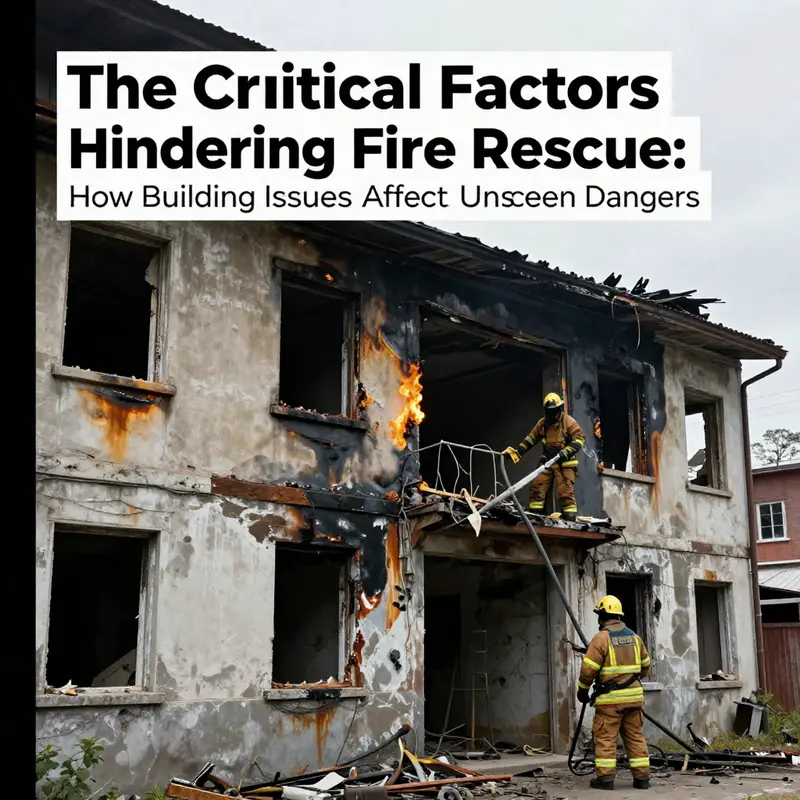

When Structures Turn Barriers: How Building Design Flaws Shape Fire Rescue Outcomes

Fire safety design is a critical partner in how quickly people can escape and how effectively responders can reach them. In many fires, the arrangement of spaces, materials, and systems determines whether a room becomes a refuge or a trap. Structural flaws, poor compartmentalization, and gaps in egress planning can accelerate heat and smoke spread, shrinking evacuation windows and complicating rescue operations. Modern research combines computational evacuation models with empirical data to reveal bottlenecks before a fire starts, guiding safer layouts and better maintenance.

Age, maintenance, and the behavior of occupants all shape outcomes. Aging structures may hide deterioration that undermines fire resistance and door integrity, while ongoing upkeep ensures life-safety systems perform as designed. Elevators, shafts, and stairwells must be considered not as convenient shortcuts but as potential hazards under fire conditions, demanding thoughtful design, shielding, and, where necessary, architectural safeguards that favor stairs and protected routes. The result is a rescue environment where pathways are predictable, exit routes are clearly marked, and occupants act with confidence rather than panic.

Ultimately, the goal is to align architecture, human behavior, and rescue operations so that design choices expand the window for safe egress rather than shrinking it. Through simulation-driven planning, rigorous maintenance, and data-informed codes, buildings can be made more navigable for both the people inside and the teams that save them.

Final thoughts

The interplay of environmental hazards, individual behavior, and systemic failures creates a challenging landscape during fire emergencies. From delayed detection to structural flaws, recognizing these factors will empower businesses and individuals alike to adopt proactive measures that enhance safety. Emphasis on fire safety training, swift detection systems, well-planned evacuation routes, and stringent building codes can together bolster the chances of successful rescue during fires. The goal is clear: prevention and preparedness will significantly improve survival during emergencies.